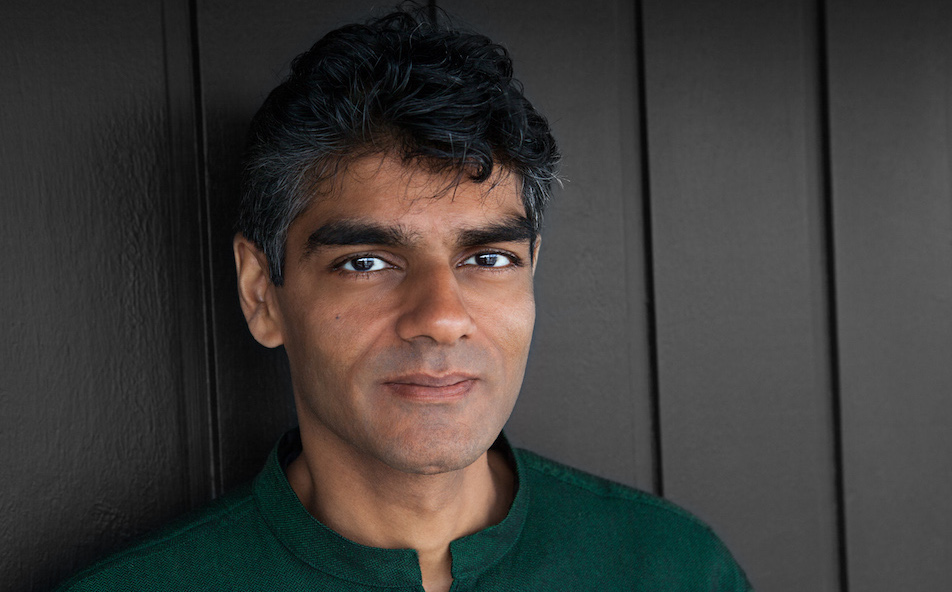

Raj Patel

Don’t let the jaunty title fool you. A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things (University of California Press, $24.95) by Raj Patel and Jason W. Moore is a serious and sophisticated approach to the socioeconomic forces that over six centuries have brought our world to its present ecologically perilous state.

Subtitled “A Guide to Capitalism, Nature, and the Future of the Planet,” the book explores how capitalism as we know it arose from the ruins of the European Middle Ages and grew and spread on the back of “Cheap Nature,” “Cheap Money,” “Cheap Work,” “Cheap Care,” “Cheap Food,” “Cheap Energy,” and “Cheap Lives.” The problem, they say, is that the age of cheap things is coming to an end. The challenge is what kind of age will come after.

Patel is a writer, activist and research professor at the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas. Moore is an environmental historian and historical geographer at Binghamton University in New York state and is coordinator of the World-Ecology Research Network.

On his website, Patel notes dryly that he “has degrees from the University of Oxford, the London School of Economics and Cornell University, has worked for the World Bank and [World Trade Organization], and protested against them around the world.”

He discussed his new book with TCN senior editor Fritz Lanham. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

+++

You use the term “world-ecology” to describe your approach in this book. Could you explain what you mean by that?

In academic circles there’s a school of analysis called world-systems theory, and that works not by comparing and contrasting, for example, different countries but by showing how different countries make up a wider world and looking at the dynamics between these countries.

What we’re doing with world-ecology is building on that to think about how we can use economic and sociological and ecological analysis all together to show the relationships between different parts of the world.

So it’s not the ecology of the planet Earth but rather the relationships of power between different entities. It puts what we call nature as well as economic and social relations on a par with one another.

Let me ask you about the title of the book – A History of the World in Seven Cheap Things. In most contexts, if something is cheap that’s a positive. But when you describe nature or money as cheap, that’s a pejorative. Talk about how you’re using the word cheap here?

One of the arguments we’re making is that the ecological and social system that has resulted in our destruction of the planet and a great deal of social turmoil has operated by not paying its bills. Whether that’s dodging responsibility for ecological consequences or underpaying workers or taking the work of care- and community-building for free or burning through abundant sources of energy, capitalism’s guiding principle – the mechanisms through which vast profits have been generated and also vast social and ecological conflict – is by not paying your bills, by keeping things cheap.

That’s what the word cheap is doing in our title. It’s both an acknowledgment of how capitalism operates but also that nothing is ever cheap forever. That’s what we’re also pointing out in the title: The seven things aren’t going to be cheap for much longer. And if they’re not going to be cheap for much longer, we really ought to be having a look at the kind of social and ecological systems that we would rather have come next. Because capitalism can’t sustain itself without these seven cheap things.

That’s what the word cheap is doing in our title. It’s both an acknowledgment of how capitalism operates but also that nothing is ever cheap forever. That’s what we’re also pointing out in the title: The seven things aren’t going to be cheap for much longer. And if they’re not going to be cheap for much longer, we really ought to be having a look at the kind of social and ecological systems that we would rather have come next. Because capitalism can’t sustain itself without these seven cheap things.

How did you come up with those seven cheap things? Could the list be longer or is there something special about those seven?

One could envision an infinitely long list, but those seven characterize the sorts of relations that happened when capitalism began. In looking at those seven, we’re both providing a history for anyone who’s interested in how capitalism emerged through climate change and through disease in Europe in particular and we’re suggesting that capitalism was the alternative because it was able to avail itself of these seven cheap things.

So you’re not using capitalism as meaning simply the process by which people buy and sell goods and services at a profit. You’re using it in a more precise sense.

That’s right. People have been buying and selling things and making money for millennia. That’s not what capitalism is at all.

We’re using the term in a very specific sense. We want to show what’s different about this civilization, the civilization we’re in at the moment. This civilization has a relationship with the rest of the planet that is very different from every other human civilization.

Sure, every other human civilization has bought and sold things, every human civilization has eaten animals and culled plants. But what’s different about ours is the relationship between humans and the rest of the planet.

We trace that to the 15th century and to the emergence of the distinction between society and its opposite. The opposite of society becomes nature. No other human civilization has that distinction. You have lots of ways of collectively referring to groups of humans, but it’s only under capitalism that the opposite of nature is society and vice versa. That’s what we see as sort of the original sin of capitalism.

As soon as you start operating under those assumptions, the natural world becomes yours to plunder and trash. And certain kinds of humans get placed into the natural world – the savages, the people who become slaves, women. These ideas of nature and society are the ones from which we see a great deal of other trouble arising.

I was interested in your argument about the role that frontiers have historically played in the advance of capitalism. You write, “Capitalism not only has frontiers; it exists only through frontiers.” Could you give an example of what you mean?

We use Christopher Columbus as exhibit A of the guy who is always there when cheap things are being exploited. But we can also think about our 21st century mega-entrepreneurs, people like Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk. Bezos is on record as saying he’s very interested in colonizing the moon so he can create an entrepreneurial world up there. And Musk is interested in colonizing Mars. The language is unabashed. That need for new frontiers to explore and exploit is something that even as we were writing the book it came increasingly clear to us that this was an extreme area of interest to the world’s entrepreneurs.

So what is the solution to our problems here? What can we do to improve the world around us?

What we are excited about is how many groups are already throwing themselves at these problems quite thoroughly. We aren’t particularly fans of Soviet-style state socialisms. If you want to see environmental destruction, Russia is a great place to look.

We are excited by movements for social change that stitch things together. So, for example, I work with groups like La Via Campesina, an international peasant group with 200 million members, including members in the United States, who are not just interested in valuing food but also are taking strong stands against domestic violence and the exploitation of women and climate change.

Or movements of native lives, for example, that are about stitching together the idea of recognizing the importance of life and new relationships to nature and are against domestic violence. All of this breaches the silos of what used to be a rather tepid kind of imagination for change. We think there are very interesting things happening in the union movement in the United States.

So we’re not expecting scenes of big transformations tomorrow, but when change does happen, it can happen very fast, and it happens not because of any one individual’s consumption decisions or buying green or whatever, but through big movements of big change.

+++++

Fritz Lanham is a senior editor of Texas Climate News. An independent journalist in Houston, he was books editor at the Houston Chronicle for 16 years.