Beaumont neighborhood flooded by Hurricane Harvey

Update, Dec. 14, 2017: This article, originally published Dec. 8, has been revised and updated to include subsequent news.

+++

By Bill Dawson

Texas Climate News

Manmade climate change made Hurricane Harvey’s catastrophic rainfall – which exceeded 50 inches in some places – worse than it would have been without pollution-fueled global warming, according to two new scientific studies released this week.

The findings, released at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in New Orleans, follow a national opinion poll that found more than half of Americans already thought climate change boosted Harvey’s destructiveness.

One of the new studies, conducted by an international scientific consortium called World Weather Attribution, calculated that global warming had made Harvey’s rainfall about 15 percent more intense and made such a precipitation event three times more likely.

“These results make a clear case for why climate-change information should be incorporated into any plans for future improvements to Houston’s flood infrastructure,” said Antonia Sebastian of the city’s Rice University, a study co-author.

“The past is no longer an accurate predictor of present or future flood-related risks,” Sebastian said in a university release. She is a postdoctoral research associate at Rice’s Severe Storm Prediction, Education and Evacuation from Disasters Center.

The second new study about Harvey, conducted by scientists at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, calculated that human-caused climate change made the rainfall accumulations recorded in “the most affected areas of Houston” at least 3.5 times more likely.

Manmade climate change increased those accumulations by as much as 38 percent, the Lawrence Berkeley researchers concluded.

Michael J. Wehner, a study author, told the New York Times the 38-percent figure surprised him – he had expected to find only a 6-to-7-percent boost from human influence.

The new studies add to a growing body of research findings quantifying the role of climate disruption from fossil-fuel pollution in Harvey’s severity.

A study by MIT atmospheric scientist Kerry Emanuel, published in November in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, concluded that global warming made Harvey’s catastrophic rainfall totals far more likely. Emanuel calculated that a storm depositing more than 20 inches of rain on Texas was six times more likely today than it was in the latter part of the 20th century.

Such findings are among the latest in a series of warnings by scientists that manmade global warming is boosting the number and severity of extreme weather events, like Hurricane Harvey and recently raging wildfires in Southern California.

A report last year from the National Academy of Sciences addressed the issue:

As climate has warmed over recent years, a new pattern of more frequent and more intense weather events has unfolded across the globe. Climate models simulate such changes in extreme events, and some of the reasons for the changes are well understood. Warming increases the likelihood of extremely hot days and nights, favors increased atmospheric moisture that may result in more frequent heavy rainfall and snowfall, and leads to evaporation that can exacerbate droughts.

Climate-action proponents point to such expert conclusions to argue for policies to fight manmade warming. Opponents of such pollution-reducing action, for their part, often downplay, dismiss or deny the strengthening scientific consensus about weather extremes.

Who’s winning this struggle for public opinion? Judging from a new national survey, conducted from Oct. 20 to Nov. 1 by researchers at Yale and George Mason universities, climate-action forces and the scientists they cite are proving to be more persuasive. From the pollsters’ report:

Nearly two in three Americans (64 percent) think global warming is affecting weather in the United States, and one in three think weather is being affected “a lot” (33 percent), an increase of 8 percentage points since May 2017.

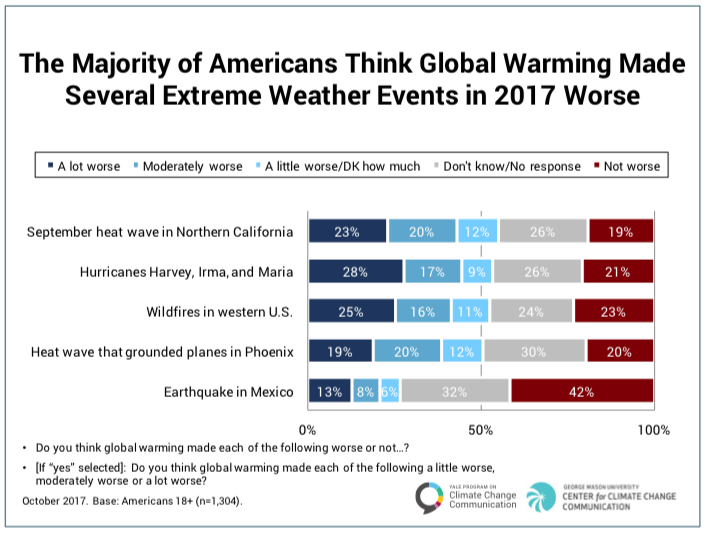

A majority of Americans think global warming made several extreme events in 2017 worse, including the heat waves in California (55 percent) and Arizona (51 percent), hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria (54 percent), and wildfires in the western U.S. (52 percent).

Other findings in the opinion survey documented increasing public concern about climate change – a trend running counter to the Trump administration’s dismissive stance toward climate science and its multiple initiatives to roll back the Obama administration’s policies to reduce greenhouse pollution.

Sixty-three percent in the latest survey, for instance, said they were at least “somewhat worried” about global warming. Twenty-two percent said they were “very worried” – the largest portion since the Yale-George Mason climate polls began in 2008, and twice the percentage of the “very worried” segment of the population in March 2015.

Forty-two percent, meanwhile, said they believe global warming is hurting Americans “right now.” That marked a 10 percentage-point jump since March 2015 in those perceiving harm “right now.”

Sixty-seven percent (up 11 percentage points since March 2015) said global warming is “extremely” (12 percent), “very” (19 percent), or “somewhat” (37 percent) important to them personally.

+++++

Bill Dawson is the editor of Texas Climate News.