Left to right: Michael Sorrell, president, Paul Quinn College; Dale Ross, mayor, Georgetown, Texas; Ken Smith, president, Revitalize South Dallas Coalition

By Randy Lee Loftis

Texas Climate News

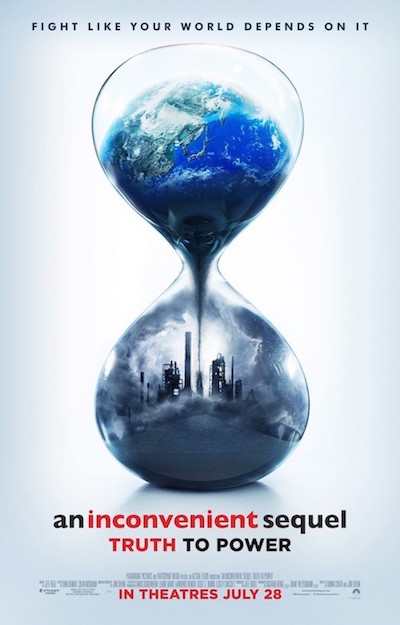

DALLAS – Al Gore’s new documentary on climate change, “An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power,” is a narrative of pressing on through loss – over and again.

“If I said there haven’t been times when this felt like a personal failure on my part,” a grim and candid Gore allows at one point, referring to the lack of real climate progress, “I’d be lying.”

The film, the follow-up to Gore’s 2006 “An Inconvenient Truth,” resonates in different ways – and in some unlikely places.

One place is Georgetown, the affluent, heavily Republican city of 50,000 north of Austin that has switched its city-owned electric utility to 100 percent renewable energy – wind and solar. Mayor Dale Ross, an avowed conservative, maintains in the new film that it’s about saving money. But deep into a conversation with Gore, he admits a concern for clean air and the children afflicted by coal’s pollution.

Another is the swath of Dallas south of downtown, including some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods, seemingly far from the concerns of an entire planet. Highland Hills is the home of Paul Quinn College, a historically black, four-year institution where President Michael Sorrell speaks of hope, work and sustainability. South Dallas-Fair Park is a community of high unemployment but also, in the view of Revitalize South Dallas Coalition president Ken Smith, deeply held values and great ambitions.

On the evening of July 26, Ross, Sorrell and Smith watched a screening of “An Inconvenient Sequel” at Dallas’ Magnolia Theater, then talked before a packed house about what the film, climate change and sustainability mean in disparate parts of Texas. I served as moderator.

The film shows Gore acknowledging a Western debt for past environmental damage by negotiating with leaders from India on a solar intellectual property pact that Gore hopes will seal that energy-hungry country’s vote for the Paris Climate Agreement. In Dallas, the three Texans discussed how such global spheres touch – or sometimes miss – the local.

And Smith and Sorrell talked about the nexus between the Paris Agreement and a burning, illegal dump in Dallas.

Following are edited excerpts of their conversation. Video of the full discussion is available on the Facebook page of the event’s sponsor, EARTHxFilm, the film arm of EARTHx, formerly Earth Day Texas.

+++

Michael Sorrell

We became engaged in the issue of our environment and sustainability when we turned our football field into an organic farm. We did so to call attention to the fact that the area surrounding our institution, which is in the Highland Hills area of Southern Dallas, is a food desert. But we also did it to begin to teach our students the importance of using their voice and disturbing the narrative of poverty and pitifulness. We tell our students life is not about pity; it’s about partnerships. A slight change in how you perceive yourself and in how you engage changes everything.

We now are engaging in what we consider our next phase, which is how do we teach students from the inner cities of our country – 85 percent of our students are Pell grant eligible – how do we teach those students about the role that they must play in the environment and sustainability and climate change? How do we teach them to be consumers in a way that allows them to do more than just address the issue from the sense of this is all we can afford to do? They must have a bigger role to play, and we are teaching them that role now.

Dale Ross

We had two goals [with Georgetown’s switch to renewable energy]. One, we wanted to eliminate price volatility in the market. And two, we wanted to mitigate or minimize regulatory risk when it comes to those knuckleheads in D.C. We were able to do that. We have long-term contracts, 25 years. And I don’t see how you’re going to regulate wind turbines. They don’t put any pollutants in the air, and the same thing for solar panels. So I think we’re on the path.

Your federal elected officials are not the ones that are going to lead the charge on renewable [energy]. It’s going to be mayors and city council members and county commissioners. We’re the ones that are responsible for providing electricity to our citizens, not the federal officials.

Ken Smith

The thing that hit me about the conversation, the meeting between [Gore and] the [Indian] energy minister in the film, was that I saw Gore representing a former colonial power now talking to, as an equal, a country that has a billion people, and more people without energy than the entire number of people who live here. But they were across the board as equals, whereas 20, 30, 40, 50 years ago, they were not equal.

When I was growing up [in South Dallas-Fair Park], it was a really a great place to live. I would not choose to live anyplace else. But we had some environmental issues that were very deeply seated. My middle school, Pearl C. Anderson Middle School, which is closed down now, was literally across the alley was a slaughterhouse. We could literally hear the cows being killed, literally maybe about 20 yards down from the playing field. Down the street, on Lamar Street, we had nothing but metal recyclers. We had the huge Procter & Gamble plant. And the Procter & Gamble plant would emit this aroma and odor that was so nauseous that we would have to get out of school because it was so bad. This was in the 1960s.

For 15 years in Dallas, from 1982 to 1997, there was a landfill [the privately owned Deepwoods dump, which operated without permits and in defiance of hundreds of city citations] in Oak Cliff that was polluting so badly that you actually had 18-wheelers and huge rock haulers going through the middle of the streets and dumping everything. That landfill caught on fire two times, and that fire lasted for six months. Six months. And today – I don’t want to be negative; I want to be positive – today that is where they are building the Byron Nelson golf course. That is where the Audubon [the Trinity River Audubon Center] is and the Texas Horse Park. So we could take a negative if we want to and turn it into a positive, but we have to have a common vision. That was the relationship that I [saw in] that video. At the end, India came into the fold and agreed to the renewable energy, but the funding for it came from the countries that they thought were holding them down.

Michael Sorrell

That landfill is across the highway from our college. All right? So I want to put this into perspective for you. [Sorrell noted that Paul Quinn shares a Methodist background with Southern Methodist University, in wealthy University Park.] Can you imagine a landfill being a mile and a half from the campus of SMU? Can you imagine a landfill being a mile and a half from the Park Cities?

Highland Hills is a community that has held on, fighting for dignity, fighting for respect, constantly being promised things that never quite showed up. So I think it’s amazing the golf course is being built. I think it’s amazing that the Audubon – I think all of that’s great. But there’s still a landfill. It’s just a little further south [the city’s McCommas Bluff landfill].

And when we talk about how we engage in personal responsibility, it’s a really interesting conversation – to say to the students and to say to their families and their parents, hey, we have a responsibility for doing A, B, C and D. And then they look back at you and say, well, whose responsibility was it for my community to be free of stray dogs? Whose responsibility was it for my community to have curbs? Because if you come to certain parts of the southern part of our city, there are no curbs. Whose responsibility is it for my children to go to schools that have the supplies that are needed?

So we fast-forward this to a conversation such as tonight. And what you’re saying to people is, we have to do this to promise a better tomorrow. But yet, folks are looking and saying, are you kidding me? What about my today, right? Until you can talk to me about a better today, I question my role for a better tomorrow. And I know that because I’ve had people tell me that. I’ve had my students say that. I’ve had their families say that.

So we fast-forward this to a conversation such as tonight. And what you’re saying to people is, we have to do this to promise a better tomorrow. But yet, folks are looking and saying, are you kidding me? What about my today, right? Until you can talk to me about a better today, I question my role for a better tomorrow. And I know that because I’ve had people tell me that. I’ve had my students say that. I’ve had their families say that.

And so what we have to do is find a way to allow people to express their frustration with how things have been as a pathway for where they think they can be tomorrow. Which means we have to listen to some conversations that are uncomfortable. We have to give people the space to be honest and to be authentic. And then we have to carve out roles which make today better so that they can believe in tomorrow.

And as I look at this, and as I thought about how India came to the table, I don’t know if I think that that’s how the rest of our communities get there. Because we are in a time where there doesn’t seem to be a lot of compassion or willingness to accept responsibility for people’s plights.

I think the path forward for a lot of these conversations starts with things that our universities can do. We can create level playing fields and engagement opportunities that give everyone a chance and give people a seat at the table without making them feel as if the table isn’t for them. We have to engage. We have to provide opportunities. And I’m proud that we’re able to do that at Paul Quinn.

Dale Ross

All politics is local. The people demand a certain level of results from their leaders. And if they can’t get those results done, you change them out. The local leaders are the ones that can make the most progress on climate change. They can make the most decisions about whether their community is going to have renewable energy or not. You can’t rely on the state or the federal government to make those decisions for you. The people need to rise up and demand from their elected leaders those things that are important to them.

If climate change is important to you, talk to your local leaders and see where you get your electricity from. Because we are at a tipping point with renewable energy. If you’re taking care of the folks you’re elected to serve on an economic level, then you get to go to a higher level and take care of some of the other issues.

Ken Smith

I wrote down the things that struck me about the film. Mr. Gore said suffering has a way of bringing us closer together. Isn’t that strange? I believe that’s very true. And another point that I got from it was progress and change often result from disasters and tragedies. And the pope said that environmental disasters have the greatest impact on the poorest. I agree.

Just like the U.N. secretary said in that little private conversation, to Mr. Gore, you have to listen. We can’t go over and say this is what we want you to do, if we’re talking to another country. We have to listen to what they have as needs and partner together so that if you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.

Michael Sorrell

I don’t know if suffering brings us closer together. I think it depends on the length of time that people have been suffering. If you’ve been suffering too long, I think you can give up hope. What can our communities teach the climate movement? I think we can teach them about resilience. I think we can teach them about the length of time that it takes to engage in a fight. Because this is not a short-term fight.

I do agree politics are local. I think there’s a lot that can be done locally. But there’s an awful lot of damage being done nationally. I also think that a significant education campaign has to occur to show exactly why this is important. And not in a way where you’re, you know, we can call it the India effect, where you are preaching to someone from a position up high, but more from a shoulder to shoulder engagement, where we are in this together.

So I think it’s a coordinated effort, that it requires education, collaboration and patience.

Dale Ross

If you look at the Dallas area, the number of children that have respiratory illnesses is just off the charts. Because if you go from Texarkana to San Antonio, you have all these coal-producing plants. And they produce coal with lignite, which is the nastiest kind of coal. So you have all these children that are getting sick in the Dallas area because it really just puts a haze over the city. The kids can’t go out to play. And when they do get sick – you know, you talk about economics – there are a lot of families that cannot afford their medication. That’s probably the biggest thing with me, the climate change and the health hazards that it presents.

Michael Sorrell

I’m going to take a really aggressive, perhaps unrealistic stance at this stage. I think that you have to close coal plants. I think we know enough now at this stage, the damage, that we really have to ask ourselves just what are we doing.

Dale Ross

But you know, the coal industry is going to collapse. It’s not going to be able to compete with [renewables]. You know, there are only about 30,000 miners left in this country, and it’s dwindling every day, compared to 100,000 solar jobs being created. [Read PolitiFact’s take on solar versus coal jobs.] So I think the market will take care of that. Because we all know there’s no clean coal, and it’s very expensive to mine.

Michael Sorrell

The only thing about that is that gradual collapse will leave people without jobs who don’t get the message. I think we’ve got to be proactive and retrain people so they can have as soft a landing as possible.

Dale Ross

That can be solved just like [it was with] the tobacco industry. There was a program of grants to try to transition the tobacco growers into some other trade. The same thing can be said for the coal miners. There’s a lot of opportunity in the wind and solar industry.

Michael Sorrell

You are rapidly becoming my favorite Republican.

Ken Smith

If this conversation were in South Dallas-Fair Park – environmentalism and climate change and things like that – people would say, huh, what are you talking about? But they would interpret environmentalism as, can we get the train that goes from Spring Avenue all the way past where Pearl C. Anderson used to be and all the way back to Bonton [a Dallas neighborhood] to stop blowing its horn at 1 a.m., 3 a.m. and 5 a.m.? That’s environmental, isn’t it? They may interpret [environmentalism] in a different way.

The statistic [for unemployment] in Dallas is 4 percent, for the metro area is 3.8 percent, and in South Dallas-Fair Park, is about 50 percent. So that’s environmental, I think, from the standpoint of the people who live there, but it may not be in the context of the movie that we see.

If we continue to have dialogue and discuss and listen, then we can both share each other’s burdens and come up with a vision for our communities. Because our people perish for the lack of vision, if I may be biblical.

Dale Ross

On a local level, if your kids are getting sick because of the air they’re breathing, I think that’s a real-world problem. There’s the tie-in to the environmentalism. Because if you don’t clean up the air, your kids are either going to have to stay indoors or they’re going to continue to get sick.

Michael Sorrell

Maybe part of this is reframing the narrative so that climate change and environmentalism don’t feel like a luxury item.

Ken Smith

Anybody can use data, right? But you cannot argue with a person’s experience. Because that belongs to them. They wrote it. They lived it. And they’re telling it. So testimonials are a way to get at that story.

And let the people from Bonton tell the story of how they’re changing their community through urban agriculture. And how seven guys who were formerly gangbangers are now gardeners who are leading their families and are making a living and have changed that community because they were connected to something better and bigger than themselves.

You get that [kind of] personal story. And that’s what I loved about the film.

+++++

Randy Lee Loftis is a senior editor of Texas Climate News. An independent journalist based in Dallas, he also teaches at the University of North Texas.