This article is part of TCN’s occasional series, Health+Climate.

+++

By Bill Dawson

Texas Climate News

Floods. Storms. Insect-carried diseases. Deteriorating air quality. These are a few of the threats to human health and safety that scientists say will increase because of warming-fueled climate change.

A recent study led by University of Hawaii at Manoa researchers looked at another health hazard on that list – extreme heat waves and how they will multiply.

The scientists incorporated both temperature and humidity in their projections of potentially deadly heat-related conditions in coming decades. The results are not encouraging for Texas, a place already well acquainted with hot-weather extremes.

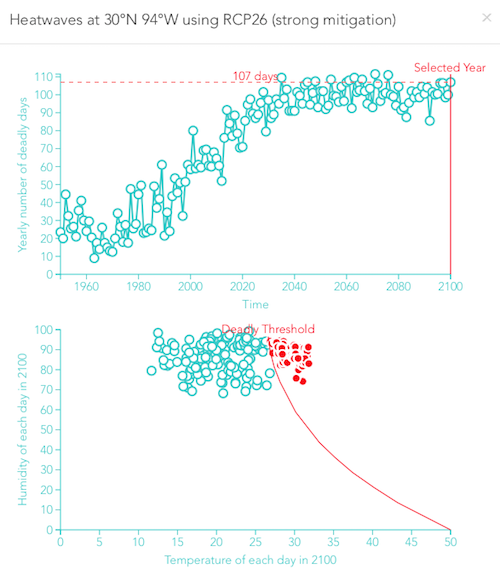

In Houston, for instance, even in a scenario with “drastic reductions” of emissions from heat-trapping fossil fuels, the researchers projected the number of days when combined heat and humidity can be lethal would rise from about 75 per year now to 107 in 2100. That’s about a 50 percent jump.

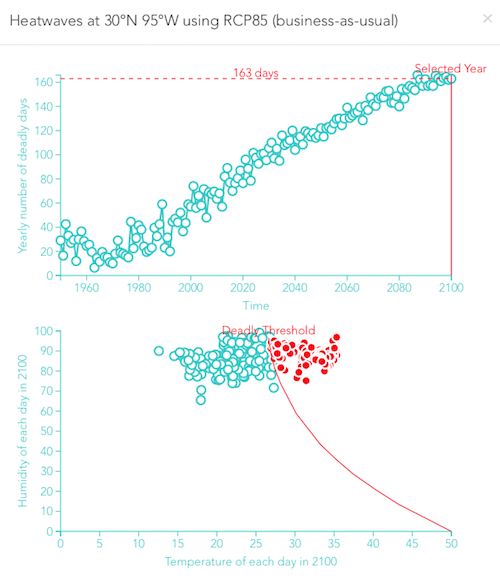

If emissions continue to increase at current rates, however, Houston’s number of days with deadly heat-and-humidity conditions would more than double to 163 per year by the end of the century, the researchers projected.

In the scenario with growing emissions, weather conditions would exceed a potentially fatal threshold for “the entire summer” in Texas’ largest city, an announcement of the study noted.

Future heat: Houston

Researchers’ projection of heat waves in Houston in 2100 with aggressive reduction of global warming pollution.

Researchers’ projection of heat waves in Houston in 2100 with continued growth of global warming pollution.

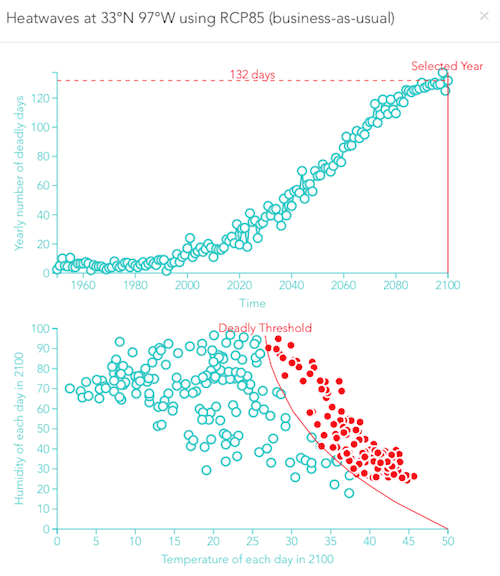

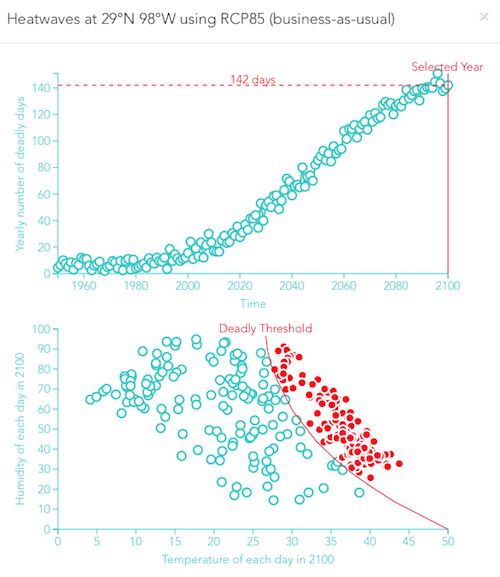

The charts above were generated by a web application the researchers developed to display the number of days in different emission scenarios when heat and humidity will combine to cross a deadly threshold at any given place.

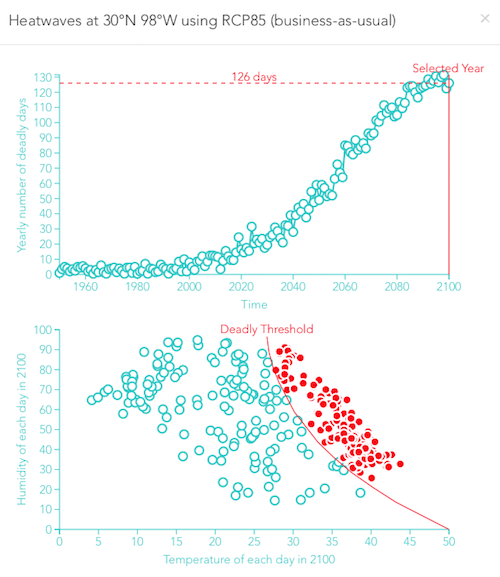

The application indicates that with emissions continuing to rise, they project the number of days with potentially deadly conditions would go from about 20 now in Austin to 126 in 2100, from about 25 to 132 in Dallas, and from about 30 to 142 in San Antonio.

Future heat: Austin

Researchers’ projection of heat waves in Austin in 2100 with continued growth of global warming pollution.

Future heat: Dallas

Researchers’ projection of heat waves in Dallas in 2100 with continued growth of global warming pollution.

Future heat: San Antonio

Researchers’ projection of heat waves in San Antonio in 2100 with continued growth of global warming pollution.

Camilo Mora, a geography professor at the University of Hawaii and lead author of the study, warned upon its release last month that the findings foretell public-health challenges even with major cuts in greenhouse gases:

We are running out of choices for the future. For heat waves, our options are now between bad or terrible. Many people around the world are already paying the ultimate price of heat waves, and while models suggest that this is likely to continue, it could be much worse if emissions are not considerably reduced. The human body can only function within a narrow range of core body temperatures around 37 degrees C (98.6 F). Heat waves pose a considerable risk to human life because hot weather, aggravated with high humidity, can raise body temperature, leading to life-threatening conditions.

In a far-reaching review of records related to heat waves and mortality, the research team discovered 1,900 cases since 1980 in which high temperatures were documented to have been fatal. Analyzing climate data for 783 of those events, which affected 164 cities in 36 nations, they determined the threshold when combined temperature and humidity can kill.

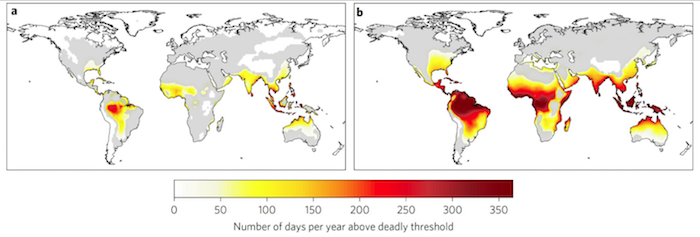

They determined that the threshold is crossed – potentially deadly heat/humidity conditions occur – for at least 20 days a year in areas where 30 percent of the world’s population lives.

If there are what the scientists called “drastic reductions” of greenhouse-gas emissions, they projected just under half (48 percent) of people worldwide would be affected in the same way.

If emissions keep growing at current rates, they calculated, nearly three-fourths (74 percent) would live in areas where the threshold is exceeded on 20 or more days a year.

Expanding deadly heat waves

These maps show the University of Hawaii-led researchers’ projections of how many days heat and humidity will exceed the potentially lethal threshold in different places around the world in 2100. The map on the left represents a scenario with aggressive reductions of global warming pollution. The map on the right represents a scenario with continuing growth of emissions at current rates.

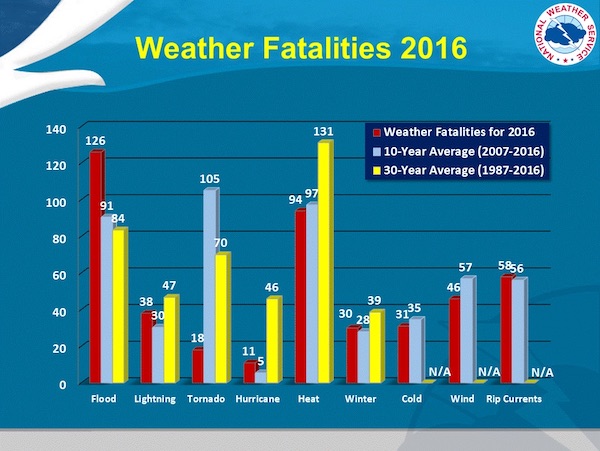

Heat is already the leading weather-related cause of death in the U.S., according to the National Weather Service. Averaged over the last three decades, there were about 60 percent more heat deaths per year (131) than deaths from flooding (84), the second leading cause of weather-related fatalities.

Considering its climate and large population, it’s not surprising that Texas has relatively high heat-fatality statistics.

In 2011, for instance, when the state experienced its most severe one-year drought and heat wave on record, it recorded 46 of the nation’s 206 heat-caused deaths, the most of any state. More recently, Texas again had the largest number of heat deaths in 2015, 48 out of 176 nationwide. It recorded 6 of 94 in 2016, ranking third behind Nevada and Arizona.

Older people are disproportionately represented in heat-fatality statistics, but extreme heat can quickly kill the young and middle-aged, too. Last month, for instance, two hikers died in West Texas of reportedly heat-related causes – a 46-year-old woman at Big Bend National Park and a 15-year-old Boy Scout at Buffalo Trail Scout Ranch near Fort Davis.

And just as these incidents sadly remind us that relative youth doesn’t necessarily protect a person against extreme heat in such exposed outdoor settings, heat itself isn’t always the primary determining factor in who dies when a protracted heat wave grips a city.

Extreme weather conditions in the prolonged Chicago heat wave of 1995 killed 739 people, medical and health experts determined. But in a subsequent, landmark investigation, sociologist Eric Klinenberg of New York University concluded that “throughout the city, the variable that best explained the pattern of mortality during the Chicago heat wave was what people in my discipline call social infrastructure. Places with active commercial corridors, a variety of public spaces, local institutions, decent sidewalks, and community organizations fared well in the disaster. More socially barren places did not.”

Writing last October in Wired, Klinenberg urged urban planners to pay attention to such social aspects, and not just rely on engineering considerations, when they build climate-change resilience in their communities:

“[Along with] the temperature of a heat wave, the height of a storm surge, or the thickness of a levee, it’s the strength of a neighborhood that determines who lives and who dies in a disaster. Building against climate change can either support vibrant neighborhood conditions or undermine them. We know how to do both.”

+++++

Bill Dawson is the founding editor of Texas Climate News.