Updated July 12, 2017

By Bill Dawson

Texas Climate News

In the never-ending battle to shape the public conversation on climate change, it’s gotten progressively harder for opponents of pollution-reducing action to contend there’s still a major scientific split over the consensus that climate disruption is mainly manmade.

An international team of researchers (including one at Texas A&M University) concluded last year that six independent studies found 90 to 100 percent of climate scientists publishing peer-reviewed research agree “humans are causing recent global warming.” Atmospheric warming is the force driving multifaceted climate change.

An earlier, widely publicized survey found 97 percent of research-publishing climate scientists accept the consensus that climate change is mainly manmade. That was a “robust” conclusion, the 2016 survey authors concluded, adding that “the level of consensus correlates with expertise in climate science.”

The breadth of scientific consensus was the key basis for agreement by 195 nations on the emission-reducing Paris Climate Agreement in 2015. At last week’s G20 summit in Hamburg, Germany, 19 of the 20 leaders spurned President Trump’s withdrawal from the climate accord, declaring it “irreversible.” The 19 nations included governments run by conservative parties (the UK and Germany, for example) and major oil producers (Russia and Saudi Arabia).

Despite its isolation on the issue, the Trump administration announced recently that it would launch a formal initiative to critique and challenge the international climate-science consensus. News accounts suggest the administration may be trying to portray the fundamental state of climate science in the public eye as “debate” rather than “consensus.”

The critique initiative was outlined in a speech last month to a coal industry group by Environmental Protection Agency chief Scott Pruitt (former attorney general of Oklahoma). Energy Secretary Rick Perry (the former Texas governor) endorsed it. Both have attracted attention lately for rejecting the idea that heat-trapping pollution is the main cause of climate change. Backing the critique project, Perry told a Senate committee human causation is still “not settled science.”

In an interview with Reuters this week, Pruitt did nothing to undercut the view that the administration hopes the critique project will sow doubt with the public about the climate-science consensus.

He told the news agency he wants it to include staging a public debate “for all the world to see,” which would perhaps be televised.

“You want this to be on full display,” he said. “I think the American people would be very interested in consuming that. I think they deserve it.”

If the project is indeed intended to sway public attitudes, officials will be swimming upstream.

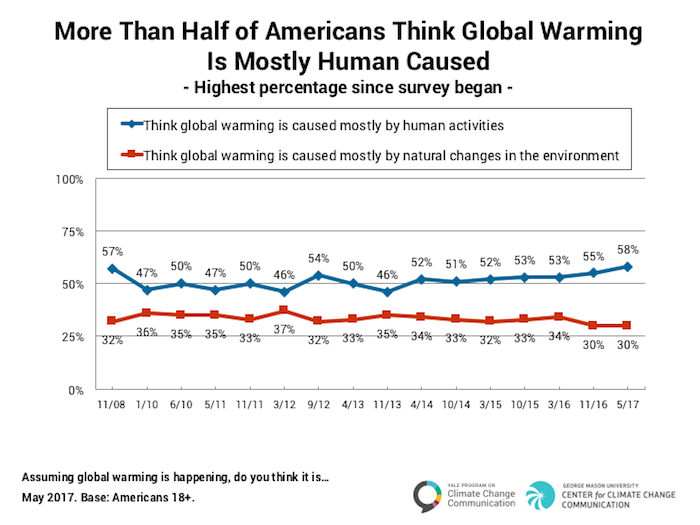

The latest in a series of national opinion surveys by Yale and George Mason universities, released last week, found a record level of public acceptance of the scientific consensus:

“Over half of Americans (58 percent) understand that global warming is mostly human caused, the highest level since our surveys began in November 2008. By contrast, three in ten (30 percent) say it is due mostly to natural changes in the environment – the lowest level recorded since 2008.”

The poll found little public knowledge of how large the consensus is, however:

“Only about one in eight Americans (13 percent) understand that nearly all climate scientists (more than 90 percent) are convinced that human-caused global warming is happening.”

Speaking to senators, Perry defended the project to challenge climate science by arguing there should be “intellectual conversation” on scientists’ basic conclusion about causation of global warming.

Critics of the effort, such as Sen. Al Franken, a Minnesota Democrat, fired back that the complex research enterprise that led over many years to the consensus included constant critiques and challenges in formal peer reviews of research findings.

The administration initiative is “fundamentally a dumb idea,” akin to questioning “whether gravity exists,” the Texas A&M atmospheric scientist Andrew Dessler told the New York Times.

A differing view was advanced by Joseph Makjut, director of climate policy at the libertarian Niskanen Center. That think tank agrees “there is little scientific doubt that the globe is warming and that industrial emissions of greenhouse gases are the main cause.”

“Both climate scientists and advocates should see opportunity” in the critique exercise, Makjut wrote in a blog post. He suggested “it could both elevate the status of climate science in the Trump administration and among Republicans, and reset how we approach climate science as a nation.”

Even if the administration’s unspoken aim is to undercut the case for climate action, the exercise could backfire if it boosts public awareness of the 90-plus scope of scientists’ consensus on causation.

A 2014 study by a group of communication researchers concluded that knowing about that scope is a “gateway belief” that often leads to support for action.

Northeastern University’s Matthew Nesbit, a communication researcher not involved with the study, summarized its basic finding:

“…Boosting awareness of scientific consensus increased beliefs that climate change is happening, that it is human-caused, and that it is a worrisome problem. These shifts in beliefs in turn increased subjects’ support for policy action, with some of the biggest increases observed among Republicans, who tend to be more dismissive of the issue.”

+++++

Bill Dawson is the editor of Texas Climate News.