By John Upton

Climate Central

Athletes and tourists who converged on Brazil for the Olympics are crowding into a country where rapid environmental change and natural weather fluctuations nurtured a viral epidemic that has gone global.

The Zika virus has exploded throughout South America, up through Mexico and Puerto Rico and into Florida, but the conditions it needed to fester in northern Brazil were rooted in urbanization and poverty. The initial Brazilian outbreak appears to have been aided by a drought driven by El Niño, and by higher temperatures caused by longer-term weather cycles and by rising levels of greenhouse gas pollution.

This combination of human and natural forces is emerging as the possible incubator of a disease that’s painfully elusive to detect, despite its cruel effects on unborn children.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued an unprecedented domestic travel advisory this week, warning pregnant women to avoid a Miami neighborhood where more than a dozen Zika cases were confirmed.

The warning came six months after the World Health Organization declared a public health emergency “of international concern” in Brazil, where the opening ceremony for the Summer Olympics occurred last Friday.

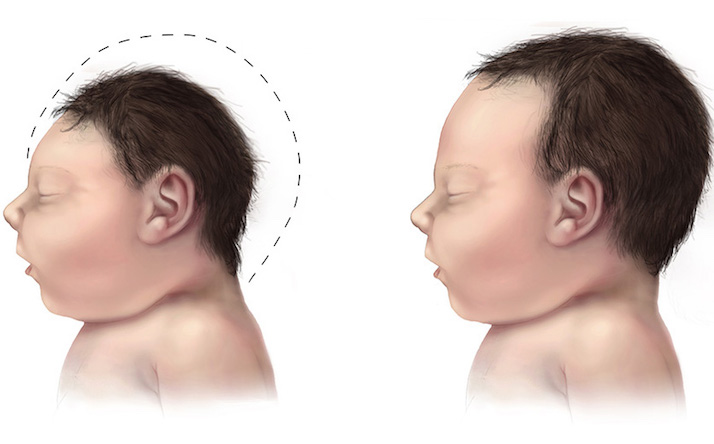

Most Zika infections produce no symptoms, turning their hosts into unwitting harbors for the disease, which is mainly spread through mosquito bites. Unborn children risk microcephaly when their mothers are infected, meaning their heads are small — the result of unusual brain development.

While the effects of El Niño and other weather cycles are beyond the control of humans, the recent spread of the disease into the U.S. is a savage reminder of the heavy toll that humans are taking on their planet — and of the potential for those changes to bite back.

Climate Central research recently showed that warming temperatures have lengthened the mosquito seasons in three quarters of major cities in the U.S.

For Americans unaccustomed to fearing tropical diseases at home, the northward march of the outbreak is delivering an exotic threat. Researchers are warning that the disease could reach the halls of power in Washington, D.C., and the dense metropolis of New York.

Mosquitoes rely on water to breed and flourish, yet a drought that beset northern Brazil amid a heatwave in 2014 and 2015 — while the disease was stealthily taking root — is thought to have worked in the mosquitoes’ favor.

That’s because households began storing more water, ushering breeding mosquitoes and their larvae inside their homes. Like other developing countries, many in Brazil lack regular access to piped water.

“If you have a drought, you don’t have reliable water access, and that makes you go and get water and store,” said Sadie Ryan, a medical geographer at the University of Florida. “By storing it, you’re creating mosquito habitat.”

Small puddles and ponds of water that accumulate in urbanized areas also tend to favor the lifestyles of the types of mosquitoes that spread Zika, compared with those that tend to thrive in more remote regions. Ryan called these types of mosquitoes “urban capable.”

“In South America up to the ‘70s, there was a really big push for vector control,” Ryan said, referring to efforts to control mosquito populations, such as spraying insecticides. “Then the money went away for it.”

Meanwhile, temperatures have been rising globally because of the polluting effects of fossil fuel-powered industrialization, deforestation and livestock farming, and natural climate cycles have been exacerbating the rate of warming in some places, such as in northern Brazil and California. That’s significant, because mosquitoes can only survive above certain temperatures.

“Once you’re over that minimum temperature, there’s nothing killing the vector,” Ryan said. “There’s nothing slowing it down.”

In a February letter published in The Lancet, a British medical journal, the University of Haifa’s Shlomit Paz and Jan Semenza of the Stockholm Environment Institute and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control reported discovering a “striking overlap” between areas in Brazil that were afflicted by extreme weather linked to El Niño, and areas where Zika was lurking one month later.

“We definitely think temperature and climate have an impact on transmission, but that relationship is often complex,” Semenza said. “It’s always very difficult to attribute one single climatic event to climate change, and then draw a causal link to health outcomes.”

More recently, a team of American and Venezuelan scientists took a closer statistical look at the relationship between climate and the Zika outbreak, and reported that El Niño and climate change were not the only important factors — though they were both important.

While the team blamed El Niño for the drought that fueled the Zika outbreak, they concluded that climate change and long-term weather cycles, such as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, which is a long-term cycle in trade winds that influences surface temperatures globally, played important roles in pushing temperatures up to those favored by Zika-carrying mosquitoes.

The findings were hurriedly pre-published without being peer reviewed on the website bioRxiv. That provided health officials and policymakers with rapid information about the findings while the details continue to be reviewed and improved.

Anthony Janetos, a professor of earth and environmental studies at Boston University, who wasn’t involved with the recent study, warned that it does not definitively prove the links that the researchers reported.

Because of that, Janetos criticized the researchers for their choice of headline for the paper, which states that the Zika epidemic was “fueled by climate variations.”

“If they’d been able to show that the same patterns occurred in other outbreak regions, such as Puerto Rico, then their circumstantial case would be stronger,” Janetos said. “But they haven’t done that.”

Ángel Muñoz, a climate scientist with affiliations at Princeton and Columbia universities who led the research, acknowledged Janetos’s criticisms, and he said the headline would be changed prior to final publication.

“This paper is not an answer for a lot of the questions that we have, but it’s an important step,” Muñoz said.

“It’s not possible right now to show a formal link between Zika and climate, because no one has enough data,” Muñoz said. “You need years, not months.”

With models warning that the epidemic will worsen before it begins to improve, the human suffering that’s expected in the months and years to come may help scientists continue to tease apart roles of natural forces in driving the outbreak from those of climate change and other problems caused by humans.

+++++

This article was originally published by Princeton, N.J.-based Climate Central, an independent organization of scientists and journalists researching and reporting on the science and impacts of climate change.