By Randy Lee Loftis

Texas Climate News

Texas has been wetter than normal of late, harking back to massive floods in May and October. Is it El Niño, climate change or other factors?

The top suspect is the periodic, temporary tropical Pacific warming called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO, for short) – helped, some contend, by global warming. That case is up for debate.

There’s also a bigger scientific mystery: whether climate change is changing the nature of El Niños. No one is sure, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said in its Fifth Assessment Report in 2013.

“The issue of whether El Niños will become more or less frequent or more or less intense under global warming is far from clear,” John Nielsen-Gammon, regents professor of atmospheric sciences and Texas state climatologist at Texas A&M University, told Texas Climate News in an email.

El Niño, by the way, refers to the Christ child due to its occurrence around Christmas.

Sea surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific rise sometimes. If a 0.5-degree Celsius (0.9 Fahrenheit) increase above normal lasts three months, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration declares El Niño conditions.

The key is the difference from normal. As climate change heats the oceans, NOAA revises what it calls normal.

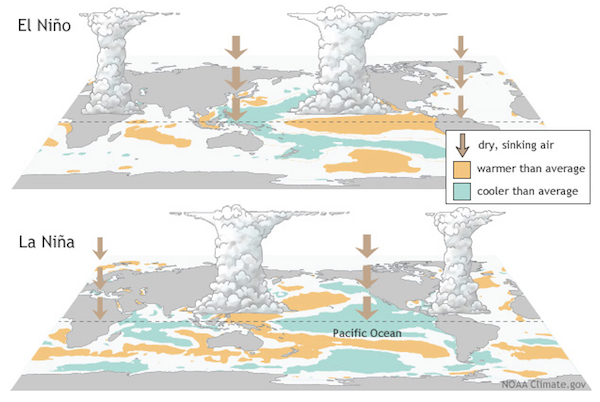

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration provides this summary description of the phenomenon that produces El Niño and La Niña conditions: “El Niño and La Niña are the warm and cool phases of a recurring climate pattern across the tropical Pacific—the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or ‘ENSO’ for short. The pattern can shift back and forth irregularly every two to seven years, and each phase triggers predictable disruptions of temperature, precipitation, and winds. These changes disrupt the large-scale air movements in the tropics, triggering a cascade of global side effects.”

ENSO can skew global temperatures, floods, droughts, severe storms and cyclones. It often brings more rain to the U.S. Southwest and less to the Pacific Northwest. Climate change could shift its influence eastward, while future ENSOs could dump huge slugs of rain as climate change strengthens monsoons.

The ENSO that developed last year, still strong, is expected to fade by early summer. For the central U.S., including Texas, NOAA sees cooler but near-normal temperatures and continued above-average rainfall through April-May.

ENSO fingerprints were on Texas’ autumn floods. “The October weather pattern fit the strong El Niño pattern almost perfectly, so it’s fair to say that El Niño helped set up the conditions that led to the October flooding,” Nielsen-Gammon said.

But what about the deadly Texas downpours of last May, when the ENSO was developing? Was global warming partly to blame?

Utah State University researchers assert that it was. They said greenhouse gas emissions brought a “significant increase” in abnormal rainfall in Texas and Oklahoma.

Others aren’t convinced. Even if global warming is strengthening the atmosphere’s response to El Niños – unproven, Nielsen-Gammon said – the current one needed little help.

“The global warming enhancement would have been small beyond what El Niño would have done anyway,” he said.

+++++

John Nielsen-Gammon is a member of TCN’s volunteer Advisory Board, serving solely in his capacity of regents professor as atmospheric sciences at Texas A&M University.

Randy Lee Loftis is senior editor of Texas Climate News. He was The Dallas Morning News’ environmental writer for 26 years.

Image credits: Photo – NASA; Maps – National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration