By Randy Lee Loftis

Texas Climate News

Texas’ ears might perk up upon mention of fossil fuels at the Paris climate talks, given the state’s petro-history and its top rank in U.S. greenhouse-gas emissions.

After all, the conference goal is an international agreement obliging nations to achieve specified reductions in these heat-trapping gases, also called GHGs.

Other Texas icons – cattle and lots of land – are also on the Paris agenda, but they’ll stir less discussion back home, and certainly less of the political bombast about President Obama’s Clean Power Plan, which seeks to curb coal use in producing electricity.

The lesser-known Texas climate players include the herds on the wide open plains (or in feedlots or dairy barns), as well as cropland, forests, wetlands and swamps. They aren’t all stereotypical Texas movie backdrops, and they’re relative climate pipsqueaks compared to all those coal plants. But they still occupy big swaths of the state and could play a role – almost certainly voluntary – as the U.S. tries to reduce its emissions.

Land’s climate role is hardly a hot topic in the United States, however. With affluence and huge industrial emissions comes the luxury of overlooking the GHGs embedded in a cheeseburger.

There’s also been a tendency for U.S. policymakers to shy away from even appearing to regulate agriculture’s environmental impact. Federal strategies on agricultural GHGs are voluntary. Last month, Texas Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller told Texas Tribune editor Emily Ramshaw that rules might make a difference in mega-emitter China, but not in America:

To make more rules, to make regulations more stringent — you can go to China and move the needle on that. But in the United States, to put in those erroneous oversights and rules, you can’t move the needle.

Michael Webber, deputy director of the Energy Institute at the University of Texas at Austin, argued for bringing agriculture under the rules in a March 5 op-ed in The Corpus Christi Caller-Times:

At a policy level, we have to stop giving agriculture a free pass. If we can drive more efficient cars, insulate our homes and use less coal, surely we can also reduce emissions from the food we eat.

To explore how Texas land has a stake in the 21st Conference of the Parties to the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, which opens Nov. 30 in the sprawl north of Paris’ city center, here’s a primer on a few sources of emissions that don’t come from smokestacks or tailpipes.

Agriculture’s climate impact tends to get lost amid the much bigger numbers from power plants and vehicles. The U.S. GHG inventory, for example, says just 9 percent of the country’s emissions come from agriculture – easily ignored in arguments over behemoths such as coal.

Globally, however, emissions from agriculture and related land uses are far from trivial — nearly 25 percent, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC’s) Fifth Assessment Report. And they’re growing, the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization reported last year.

Agricultural emissions percentages are also a marker of national poverty: The poorer the country, the bigger the share of its emissions that comes from farming and related land use.

The IPCC calls such emissions AFOLU, for agriculture, forestry and other land uses. They include methane from ruminating livestock, mostly cattle, and from rice cultivation, as well as nitrous oxide from other operations. There are also complex tradeoffs between emissions that result when forests are cut down and their stored carbon is released, and the carbon removed from the atmosphere in “sinks” that include growing forests and other crops.

Climate planners hope to slash the earth’s total emissions from agriculture and land use by as much as 80 percent by 2030, largely by reducing deforestation and improving livestock practices in developing countries.

That’s a sociological goal as much as a technological one. Agriculture employs one-third of all the world’s workers, the FAO says, especially in the poorest regions. And in a developing country, farm work is largely the task of women.

It’s easier to estimate conventional industries’ emissions than those from agriculture and the land. Methods vary and uncertainties are large (“Do you have a month?” Texas A&M agricultural economist Bruce McCarl asks his students in class notes on modeling farming-related emissions, sinks, and mitigation).

Beef or dairy, pasture or feedlot, one diet supplement or another – each changes a cow’s emissions. The depth of a rice field’s flooding alters its methane output. The age of a forest determines its efficiency at capturing carbon. The resulting numbers are iffy, but studies and examples reveal the big picture.

We start with the burps of those legendary Texas cattle.

Texas is the nation’s cattle king, with 11.8 million head on Jan. 1, 2015, about 13 percent of the U.S. total. Each has a first stomach, or rumen, that digests food through a process called enteric fermentation. The cow burps up the byproduct, methane. (Despite misplaced giggling over the source, nearly all the methane escapes from the cow’s front end, not its rear.)

Over the long haul, a pound of methane traps 25 times more heat than a pound of carbon dioxide, the principal GHG produced by human activities. The methane from all the cow burps in the country in 2013 equaled the warming power of 164.5 million metric tons of CO2. U.S. fossil-fuel burning, by contrast, pumps out that much in 11 days.

Methane emissions in the U.S. have dropped by about 15 percent since 1990 (although disagreements continue over accounting for leaks from natural gas operations). But the total coming out of cows has fluctuated only a little.

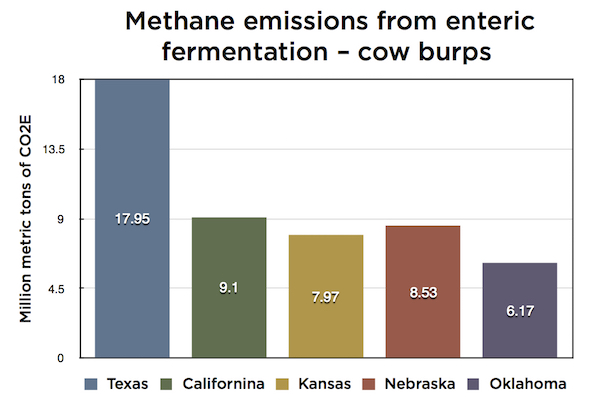

Methane emissions from cows in 2008, expressed in million metric tons of equivalent atmospheric warming power of carbon dioxide, or CO2E. (Source: U.S. Agriculture and Forestry Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990-2008)

Texas, because of its vast numbers of beef cattle, and California, because of its dairy cows, are the biggest states for bovine-burped methane, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Annual methane from Texas cows has the warming power of 17.95 million metric tons of CO2, about a couple of weeks’ worth of Texas industrial emissions.

Growing rice in flooded fields is another Texas methane source, but the state’s numbers are puny. From just over 143,000 acres of rice in 2013, Texas added about 300,000 metric tons of CO2 equivalent. Texas industries crank out that much every six hours.

Agricultural soils, of which Texas has plenty, are a big source of nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas that lasts more than a century in the atmosphere and, pound for pound, has 298 times CO2’s warming potential. The USDA cites two Texas factors that result in especially noteworthy N2O emissions from soil: irrigated cropland in West Texas, such as High Plains cotton, and East Texas hay.

At the same time, growing plants take up carbon. U.S. forests absorb and store enough carbon to offset about 13 percent of the nation’s fossil-fuel emissions, the U.S. Forest Service says, although there’s concern that climate change could reduce that ability.

The land’s ability to forgive and to help draw global links can still surprise. From deep in the body of federal research comes an unexpected Texas fact.

Although the Hollywood image of a Texas town might involve dust and tumbleweeds, nearly one-third of the land area of Texas cities is covered by trees. Together, those urban trees sequester just over 2 million metric tons of carbon a year. Adding still more trees in the state’s cities – or in forested rural regions such as East Texas – could be identified as one more way to fight global warming.

So if a sleepy afternoon beneath a shady Texas oak conjures dreams of a Texas steak and a side of Texas rice, it might also stir thoughts of autumn in Paris.

+++++

Randy Lee Loftis, an independent journalist in Dallas, is senior editor of Texas Climate News.