Sister Leticia Benavides greeted a refugee child from Guatemala last year at one of the assistance centers opened by Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley in response to the flood of unaccompanied children and other immigrants entering Texas from Central America. Pope Francis expressed his thanks for the effort this month in a “virtual papal audience” with groups in South Texas, Los Angeles and Chicago, which was hosted by ABC News.

Migration and refugees are two words that have been much in the news lately.

The migration crisis in Europe, with thousands of desperate people flooding into that continent from Syria and other troubled nations, is gripping the world’s attention. Researchers recently tied the Syrian part of that exodus to drought aggravated by manmade climate change.

The recent 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina has been a sobering reminder of scientists’ warnings that climate change, through sea-level rise and in other ways, will increase hurricanes’ destructiveness – and that a single catastrophic weather event can abruptly force tens of thousands of people to seek new homes far away.

President Barack Obama, speaking this month to an international conference in Alaska about the impact of climate change in the Arctic, cited longstanding concerns that climate change may create more refugees to underscore his call for international action at a diplomatic climate conference in Paris later this year.

If the climate-change “trend lines” charted by scientists continue, “there’s not going to be a nation on this earth that’s not impacted negatively,” Obama said. “People will suffer. Economies will suffer. Entire nations will find themselves under severe, severe problems. More drought; more floods; rising sea levels; greater migration; more refugees; more scarcity; more conflict.

In this article, TCN contributing editor Greg Harman provides an in-depth examination of the complex issue of migration driven by climate change, with particular attention to the situations in Mexico and Central America and the future prospects for climate-increased movement of people from those areas into Texas and elsewhere in the U.S. An accompanying article provides the transcript of Harman’s detailed interview with Alice Thomas, climate displacement program manager of Refugees International.

+++++

By Greg Harman

Texas Climate News

In her native Honduras, she didn’t seem a likely target for the local drug gangs. But the former cafeteria worker was marked nonetheless. Men in masks attacked her in the street, looking for keys that would allow them to slip in and out of the local school building at will. But after a nephew intervened, pulling off one of the assailants’ masks in the process, things worsened for the mother of two.

“They were calling her saying that if she reported the crime they would kill her,” said Brenda Riojas, spokesperson for the Catholic Diocese of Brownsville. Even after Paloma (not her real name) moved her children across town, the calls kept coming. The men threatened to kidnap her children. And worse.

Like much of Central America today, Honduras is a nation gripped by runaway drug violence. In 2012, the nation had the world’s highest homicide rate of 90 murders per 100,000 people, according to the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime. And in cities like San Pedro Sula that figure screams to over 180 per 100,000. (By comparison, Iraq at the height of 2007’s insurgency had an estimated homicide rate of about 62 per 100,000; the U.S. rate is less than five per 100,000.)

Paloma grabbed her children and nephew and fled, joining thousands of others believing an arduous journey of more than a thousand miles across Mexico to the United States was their best chance at survival.

An unprecedented 62,997 unaccompanied minors were apprehended in the border regions of the United States in the October-through-July period of fiscal 2014. Apprehensions of such children have dropped by about half, to 30,862, in that same part of fiscal 2015, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Apprehensions have risen this year in some areas, however, including the agency’s El Paso and Big Bend sectors along the Texas-Mexico border.

“We see these children and families as refugees,” said Riojas, describing such migrants who cross the international border into the Lower Rio Grande Valley of South Texas, where last year’s flood of immigrants prompted the Brownsville Diocese to open assistance centers to help them.

“They don’t get up one day and just decide to come to the United States for a vacation. They’re fleeing very real dangers. They’re taking all the risks of taking this journey because they still find the possibility of hope — just the chance of life.”

The pressures on residents of Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, however, don’t begin and end with drugs. Large swaths of these nations have also been gripped by their worst drought in decades. Farmers are losing their livelihoods and city dwellers are struggling to keep up with rising food prices. In Nicaragua, considered the hardest-hit nation in the region, the government responded by urging people to eat more native iguanas.

Last September, it was estimated that 2.8 million Central American residents were struggling to feed themselves, according to the United Nations World Food Programme. This year, as dry conditions continued to punish the region, U.N. representatives urged surrounding nations to “prioritize resources” to assist people there. Members of the international relief organization Save the Children say conditions have worsened since last year and predicted the situation could become a “serious humanitarian situation” if aid is not increased.

Drought and its consequences are everywhere in the news these days. Scientists recently calculated that global warming has intensified California’s record-breaking drought, now in its fourth year, by as much as 20 percent. The Syrian civil war, which has displaced millions and fed into what is thought to be the largest mass migrations since World War II, was primed by warming-enhanced drought at home that crippled growers, researchers concluded in another study published this year. And drought inspired Russia, a major supplier to the Middle East, to stop all wheat exports.

And while it hasn’t received as much media attention in the U.S., droughts of similar intensities have been unfolding across Central America, Colombia and Brazil.

Threatening social conditions may have been the principal factor compelling tens of thousands of unaccompanied children and others to enter Texas without immigration documents last year. But a variety of experts are worried that future migrations – within Central America and Mexico and into the U.S. – could very well be much larger in years ahead, and increasingly prompted by the intensifying impacts of global warming.

+++

Concerns about migration prompted by climate change are nothing new. Calling their projections “extreme” but “plausible,” a pair of researchers at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., took on the topic of abrupt climate change for the Department of Defense a dozen years ago. The thought exercise examined how the rapid onset of global warming impacts may affect the national security of the United States.

Their sweeping portrait was of a planet thrown into chaos: Conflicts over oil supplies, fishing rights, and dwindling freshwater resources rage around the world. The United States, able to achieve relative self-sufficiency, turns itself into a defensive fortress.

“Borders will be strengthened around the country to hold back unwanted, starving immigrants from the Caribbean islands (an especially severe problem), Mexico, and South America,” Peter Schwartz and Doug Randall wrote in “An Abrupt Climate Change Scenario and its Implications for United States National Security,” published in 2003.

“Tension between the U.S. and Mexico rises as the U.S. reneges on the 1944 treaty that guarantees water flow from the Colorado River,” they continued.

And looking beyond the Western Hemisphere, the researchers envisioned the U.S. confronting daunting security challenges across a globe in the grip of a fast-changing climate: “The intractable problem facing the nation,” the researchers wrote, “will be calming the mounting military tension around the world.”

Even without anything as dire as that imagined scenario, U.S. immigration policy has grown increasingly strict in recent years, particularly with regard to migrants from Mexico and Central America. The 2006 Secure Fence Act resulted in hundreds of miles of high metal barriers being constructed along the U.S.-Mexico border. Deportation numbers, rising fast for a decade already, reached an all-time high of 400,000 under President Barack Obama in 2012.

Leading Republican presidential contenders are now saying that’s not nearly enough. Businessman Donald Trump, enjoying a commanding lead in Republican presidential polling, has called for mass deportation of all undocumented immigrants in the U.S. – an estimated 11 million people – and construction of a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border to stem future illegal entries.

And Trump is far from alone among his party’s presidential contenders in urging a stern crackdown on immigration. NBC News reported last month, for example, that eight Republican candidates had endorsed the idea of ending the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of birthright citizenship for all children born in the U.S. to undocumented immigrants living here. As he abandoned his own bid for the nomination last week, former Texas Gov. Rick Perry was obviously concerned about such developments, warning that Republicans should not “indulge nativist appeals that divide the nation further.”

That’s part of what’s happening in the U.S. political arena now. It’s easy to imagine future debates over immigration issues becoming ever more intense. Looking ahead to the time when scientists project more numerous and more severe impacts from climate change, global projections of the displaced range widely in relation to a number of factors, including how much warming can be avoided by curbing emissions of greenhouse gases.

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), for example, expects between 25 million and 1 billion people to be displaced by short- and long-term disasters associated with climate change by 2050.

Climate change has already begun to impact people and deepen inequalities worldwide as the number of weather-related disasters has doubled from 200 to 400 per year in 20 years, according to a recent UNHCR paper. And the Norwegian Refugee Council has suggested that climate-related disasters may have driven as many as 20 million from their homes in 2008.

It was exactly these sorts of issues that inspired Katharine Hayhoe, the daughter of missionary parents, to study climate change in the first place. As a committed Christian who had spent years of her childhood in Colombia, she became deeply concerned about what climate change meant for the world’s poor.

“The biggest reason I study climate change is because of the impact that it has on the people who don’t have the resources to adapt,” said Hayhoe, a climate scientist at Texas Tech University and director of the Climate Science Center there. “What I learned living in Colombia is just how vulnerable people can be to what have previously been entirely natural hazards but what are increasingly becoming not-so-natural hazards.”

+++

When decades of rising temperatures and declining rainfall – attributed, in part, to climate change – created conflict between farmers and seasonal nomads sharing the same water wells in western Sudan, the resulting explosion of ethnic tensions led to the killings of hundreds of thousands. Some researchers began to posit that the genocide was the world’s first war attributable to climate change. Projections for more of the same as average temperatures continue to rise suggested the possibility of a 55 percent increase in African conflict – and hundreds of thousands more dead – by 2030.

It inspired one of the world’s leading nongovernmental organizations dedicated to supporting refugees, Refugees International, to create a full-time position to lead on the issue in 2010.

“The organization got very concerned about how climate change was going to impact displacement,” said Alice Thomas, Refugee International’s climate displacement program manager, “not just as a driver in terms of sea-level rise and island states, but as another contributing factor to displacement in poor and fragile countries.”

While scientists say a certain degree of manmade warming is now locked into the earth’s climate system, no matter what world governments do to reduce heat-trapping pollution, society’s vulnerability to those coming impacts of additional heat, drought, intensified rainfall events and sea-level rise can be reduced through preparedness and availability of resources.

A major drought in Texas, for example, can hit the state in the pocketbook and drive many out of work, Thomas said. But if a drought of the same severity occurs in some parts of Africa — think Somalia in 2011— people will starve to death. Same drought intensity, very different outcomes.

“Here we can go to 7-Eleven and get water if we don’t have water,” Thomas said, “but if you’re in a country where if it doesn’t rain you don’t have water, the situation becomes a crisis very quickly. It’s a lot more about vulnerability to these extremes than it is the extremes themselves. The impact of climate change will largely be a function of underlying vulnerability of the population it affects.”

[Read TCN’s extended interview with Thomas]

Of course, some parts of the United States are also more vulnerable to climate change than others. It wasn’t just its low-slung position on the hurricane-prone Gulf Coast that put New Orleans at increased risk. The city’s high levels of poverty made many residents especially vulnerable when Hurricane Katrina arrived in 2005.

As Hayhoe points out: “The people who had access to information and to transportation were able to get away. The people who did not have access to that struggled to get away, maybe couldn’t get away.”

It’s a point that Robert Bullard, dean of the Barbara Jordan-Mickey Leland School of Public Affairs at Houston’s Texas Southern University, drove home when he keynoted the SXSW Eco conference in Austin last October.

“We know what happened after Hurricane Katrina,” he told the audience. “But the communities that were vulnerable during the storm and after the flood, these communities were vulnerable before because of policies, because of land-use decisions, because of housing patterns, because of other kinds of policies that were put in place.”

As in Louisiana, so in Mexico.

+++

Given the growing impact of climate change around the world, researchers across academia are struggling to predict future challenges to human health and safety. Some have dedicated themselves to studying migration patterns and drought. As the United States’ most important trading partner — and part of one of the planet’s most frequented and oldest migration corridors — Mexico is the subject of much of this study.

In 1990, an estimated 5 percent of all Mexican nationals were living inside the United States. During the last years of what researchers have dubbed the “great Mexican emigration,” that number doubled to just over 10 percent in 2005. Some have blamed the importation of cheap corn from the United States following the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement. Others have spotlighted other economic hardships or changes in U.S. immigration policies.

Few, however, have explored the impact of drought on the influx, despite the frequent accounts of the migrants themselves, many of whom have been Mexican farmers claiming they were driven north because of protracted crop failures in recent years.

Studying Mexican drought and migration patterns between 1995 and 2005, a team of researchers at Princeton University found a strong correlation: the more drought, the more migration. That link led to a clarion-call warning of a massive new influx into the United States of dispossessed farming families, perhaps as many as one in 10 Mexican adults.

“Depending on the severity of crop losses, between 1.4 million and 6.7 million people would migrate to the United States by 2080,” the trio from Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs wrote in 2010.

Even those figures were probably low, they said, as crop losses from global warming in future decades are expected to be considerably higher than the 1995-2005 period that the team studied.

While the numbers are undoubtedly bleak, the Princeton authors also made one big assumption: that Mexican farmers will not be able to afford to invest in new farming equipment, such as irrigation implements, in order to adapt to changing climate conditions.

“We believe that options for mitigating unfavorable climate conditions are limited by a lack of capital for significant investments in infrastructure,” they wrote.

But is that changing?

+++

Drought has played a starring role in many of the key events of Mexico’s history. The Mayan empire collapsed, it is believed, in part because of water scarcity and overuse; Mexican independence from Spain in 1810 occurred during a period of extended drought, which likely inspired many to revolt; a century later, grinding drought in northern Mexico helped Pancho Villa mobilize an army of disgruntled peons to dismantle the feudal landowner system during the Mexican Revolution.

The country, with half its land considered arid or semi-arid, and most of its population in the water-poor north, remains extremely vulnerable to water shocks today. While as much as 80 percent of the nation’s water resources are sucked up by agriculture, many subsistence growers remain totally dependent on rainfall.

Already about 20 million people in Mexico are considered “food insecure,” according to a recent report by the U.K.’s Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies, and as much as 400 square miles of farmland are lost to desertification every year.

Pondering those unhappy statistics along with the onset of “coffee rust,” a fungal disease impacting coffee plantations from Mexico to Peru, provides a sense of the serious challenges ahead for this vulnerable country.

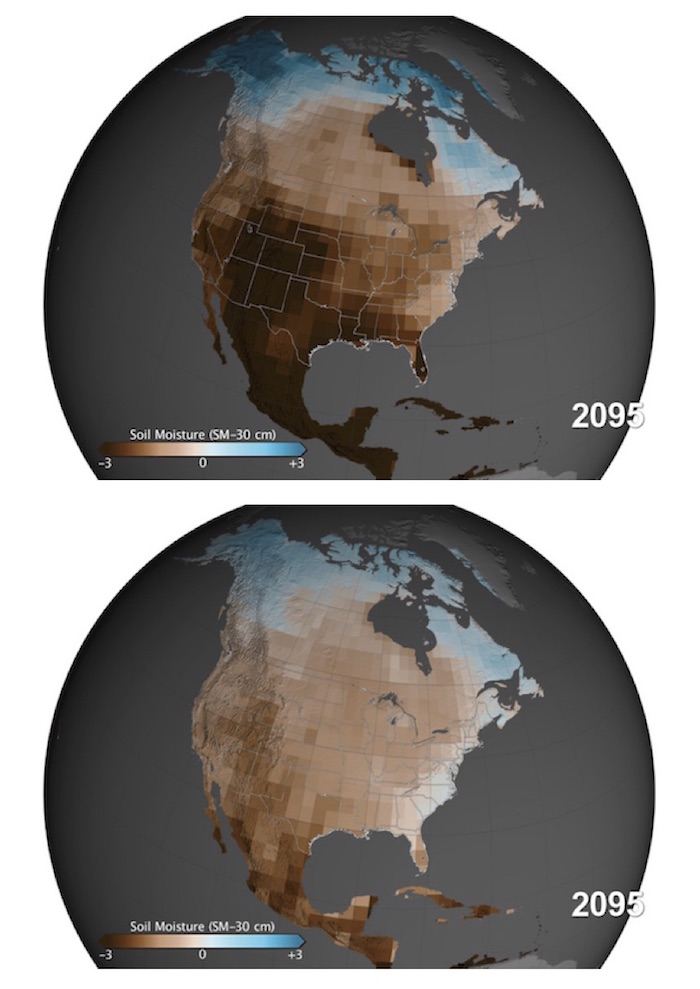

NASA: Continuing greenhouse emissions boost “megadrought” risks

Continuing emissions of heat-trapping greenhouse gases will increase the risk of severe, decades-long “megadroughts,” according to a NASA study published in the journal Science Advances in February. As these maps from the study show, projections of the lowest levels of soil moisture include large parts of Mexico and Central America. The top map represents soil moisture in 2095 in a “high emissions” scenario. The bottom map represents a “moderate emissions” scenario.

Echoing the findings of the Princeton team, a group of Mexican researchers exploring the possibilities of climate-change adaptation measures in their country wrote in a 2012 paper that most relocations away from rural areas of the country between 2000 and 2005 — both to urban areas inside Mexico and to the United States — were due to “environmentally forced migration,” drought specifically.

“Government, agribusiness and small farmers together should not only collaborate in order to mitigate the effects of greenhouse gases in Mexico, but also to prevent the increasing lack of water for agriculture by means of water-saving processes and new infrastructure for recycling,” wrote the team, drawn largely from the National Institute of Forestry, Agricultural, and Animal Husbandry Research (whose Spanish name’s acronym is INIFAP).

A National Water Plan spotlighted in the INIFAP paper blamed inefficiencies for a loss of more than 60 percent of agricultural water; outright corruption and politicization were fingered for the limited effectiveness of water management efforts; and overall improvements were said to be hampered by meager investment in science and technology.

But these challenges may also be read as opportunities, said Ignacio Sánchez Cohen, head of INIFAP’s watershed management research.

The two most important measures that Mexico can implement to prepare its population for climate-change impacts, according to the INIFAP report, are poverty alleviation and environmental conservation.

“Even though climate vulnerability is not directly associated with poverty, poor people are the most affected by extreme events,” the team wrote. “Accordingly, a development policy orientated towards poverty alleviation should be considered in any proposal for a climate change strategy.”

But the United States could also do much to ease the impact of climate change on Mexican residents, some migration experts argue.

+++

Moving in that direction would include overcoming anti-immigration sentiments with a spirit of compassion, Refugee International’s Thomas said.

“Rather than having an attitude that we need to close the border, governments need to think about how to better use migration as an adaptation strategy to climate change,” she said.

Such an approach would undoubtedly face political challenges in the U.S. For instance, two Republican presidential candidates, Florida Sen. Marco Rubio and Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, recently criticized Democrats for regarding climate change as a foreign policy and international security issue.

Even so, shifts of the sort that Thomas suggested have begun to occur in places like the Pacific Island States, where sea-level rise is forcing people in the most low-lying and isolated islands to move to larger neighboring islands, sometimes just temporarily. Central American states offer a wide variety of cross-border visas for those being driven by sudden-onset disaster. And in West Africa, some nations have entered into a “free movement of persons” agreement that has virtually collapsed the human smuggling trade there, said Walter Kälin, of the quasi-governmental Nansen Initiative.

Nansen was established by the governments of Norway and Switzerland to help nations adopt cooperative, trans-boundary strategies to better respond to disasters, including the slow-onset disaster of climate change.

Kälin, a former representative of the United Nations secretary-general on the human rights of internally displaced persons, said it is important to be more proactive to avoid the creation of more refugees.

“Refugees means people stay in their country until they really have to run to save their lives,” Kälin, a Swiss legal scholar and human rights expert affiliated with the Washington-based Brookings Institution, an influential public policy organization, told Texas Climate News.

“Then you have all the humanitarian problems, the protection problems – basically you have a mess,” he said. While refugee camps will always be needed to respond to emergencies, during slower-moving crises, like extended droughts and sea-level rise, the facilitation of migration can be an important tool that prevents needless suffering.

“During drought, part of a family moves to cities or other countries and sends money back,” he said. “Later, they come back home. We don’t need a humanitarian response.”

Nansen has conducted a series of consultations, starting in the Pacific Islands in the spring of 2013. There, representatives of 10 small island states emphasized that while they recognize rising sea levels and other climate-driven changes will require many of their residents to relocate, they want those communities to have as much say as possible over how those evacuations are handled.

According to the concluding document from the Pacific gathering, “participants stressed that having to leave one’s own country is the least preferred option. Participants expressed concern that cross-border relocation may negatively impact on nationhood, control over land and sea territory, sovereignty, culture and livelihoods.”

In December of 2013, Nansen hosted a similar gathering of Central American nations in Costa Rica. Topics ranged among related topics, including reducing the risks of disaster, displacement, human rights, and climate change. The gathering included participants from Central America, Mexico, Colombia, Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

The group discussed existing regional agreements that allow temporary trans-border migrations — including a Regional Climate Change Policy that recognizes the need for national strategies related to “the evacuation, temporary and permanent relocation and immigration of populations most affected by increased and reoccurring extreme climate.”

They also stressed that trans-border migrations have provided an important strategy for survival for many residents of the region, particularly during Hurricane Fifi in 1974, Hurricane Mitch in 1998 and the 2010 earthquake in Haiti.

“Participants recognized that climate change is increasingly affecting the region, for example, through the increased frequency and intensity of [tropical storms and hurricanes], and reduced accumulated precipitation,” the concluding document stated. “Coastal erosion, flooding, and the salinization of fresh water sources and agricultural land associated with sea-level rise have also prompted some communities, including indigenous communities, to plan for the relocation of their villages to higher ground.”

The large number of treaties existing across Central America may hold potential lessons for the U.S. for dealing with future climate-related migration. Now, the only tool the nation has is the ability to grant temporary protection status for those who have already fled disasters and entered the United States illegally.

“It’s not really for admitting people,” said Kälin. “It’s for not sending people back.”

But ideas such as those discussed at the Costa Rica meeting may have caught the interest of some in the Obama administration. U.S. immigration officials have reached out to Nansen, according to Kälin, to discuss ideas for “harmonizing” policies from Panama to Canada.

“We’re still very far away from anything binding or anything that could be implemented, but for me it was interesting to see that there is an acknowledgement that there is something we have to look at,” he said. “It is the beginning of a very long discussion.”

+++

That people will be displaced across Mexico and Central America in greater numbers in the future due to climate change is not in dispute among experts. How many people may become migrants as a result is a subject of disagreement.

Predicting only moderate impacts on migration — and this mostly occurring within Mexico — Kerstin Schmidt-Verkerk wrote in her 2012 doctoral thesis at Britain’s University of Sussex: “Alarmist predictions of large numbers of ‘climate change refugees’ are … inappropriate and policies should instead focus on the factors projected to impact most on migration under scenarios of future climate change.”

Also much in dispute – unsurprisingly, given the fiercely contentious political debate surrounding immigration issues now – is what the U.S. response should look like.

Promoting a position diametrically different from Trump’s mass deportation proposal, for instance, is Antonio Diaz, who leads an annual march in San Antonio to establish an Indigenous Dignity Day in that city, similar to the Indigenous People’s Day commemoration that Minneapolis substituted for Columbus Day celebrations. Marchers in the San Antonio event typically call for decriminalizing migration into the United States and for closing family detention centers in Texas.

Migrants from Mexico and Central America, they say, are simply following an ancient route of trade and cultural exchange that predates the founding of the United States.

“I believe all people should have the right to migrate pursuing food, shelter, well, survivability,” Diaz told Texas Climate News by email. “The case may come where U.S. citizens may need to migrate south to escape severe climate change.”

That hypothetical emigration scenario may seem far-fetched – climate experts have long said that the United States and other affluent societies have the best chance to adapt to the projected impacts of climate change. When it comes to general matters of climate-driven displacement of people, however, the U.S. is not immune.

Michael Mann, a prominent climate scientist at Penn State, discussed the issue in an interview last year with TCN.

“The streets of Miami flood every year now with the [extremely high] seasonal King tide,” he said. “If you look at Texas and Oklahoma, the heat and drought in recent years has decimated their livestock. It’s wreaked havoc on their agriculture. … We think of environmental refugeeism as something that afflicts the Third World but not us.”

But California’s severe, years-long drought is the U.S. situation that comes closest now to a scenario involving climate-forced migration, Mann said.

“It’s not just record drought [in California], it’s off-the-scales drought. There is a very real threat of conflict over diminishing water. The increasing population, decreasing water resources, increasing competition [for water] from the energy industry for natural gas and fracking,” he said.

“If the drought in California becomes the new normal, and there’s a very real possibility that it does, we are going to see people driven from their communities, driven from that state,” he added. “It will not be able to meet the water needs of its population.”

Recent reports chronicled impressive, above-expectations actions by Californians to coserve water this summer. But the process of drought-driven migration that Mann envisioned may have already begun, according to a prominent Texas expert on such subjects.

Lloyd Potter, the Texas state demographer and a demography professor at the University of Texas at San Antonio, told that city’s WOAI-AM last month that 600,000 Californians have moved to Texas since 2009. Better job prospects and a lower cost of living in Texas were two factors Potter cited as factors motivating the exodus. California’s punishing drought was the third.

Along the Texas-Mexico border, meanwhile, the flow of unaccompanied minors being apprehended has slowed this year – along with the intense media attention that last year’s throngs attracted – but the arrival of such would-be immigrants has by no means stopped.

Whatever their motivations may be, the families and children making the difficult trek into Texas are still coming in numbers large enough that they sometimes challenge the capacity of those dedicated to helping them, such as Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley, which opened the assistance centers in that region last year.

“Some days we’re still short on volunteers,” said Riojas of the Brownsville Diocese this month. “We had a large group come in, 75 refugees, and we only had four volunteers on hand that day.

“The families are arriving every single day,” she said. “We pray that what is happening here on the border will raise awareness.”

+++++

Greg Harman, contributing editor of Texas Climate News, is an independent journalist and writer based in San Antonio. He is also a graduate student in the international relations program at St. Mary’s University there.