A quick-association quiz: Which Texas president first comes to mind in connection with climate change?

A quick-association quiz: Which Texas president first comes to mind in connection with climate change?

George W. Bush? He controversially abandoned the pledge he made in his 2000 campaign to champion regulatory controls on global warming pollution from coal-fired power plants. And he spent his eight years in the White House resisting calls for him to change his mind and adopt an emission-reduction agenda.

His dad, George H. W. Bush? The first President Bush signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, a non-binding framework for later treaties that may set mandatory emission limits, at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. And he signed a sweeping overhaul of the Clean Air Act, whose many provisions included a mandatory phase-out of chemicals that deplete the Earth’s stratospheric ozone layer and also contribute to the warming trend that drives climate change.

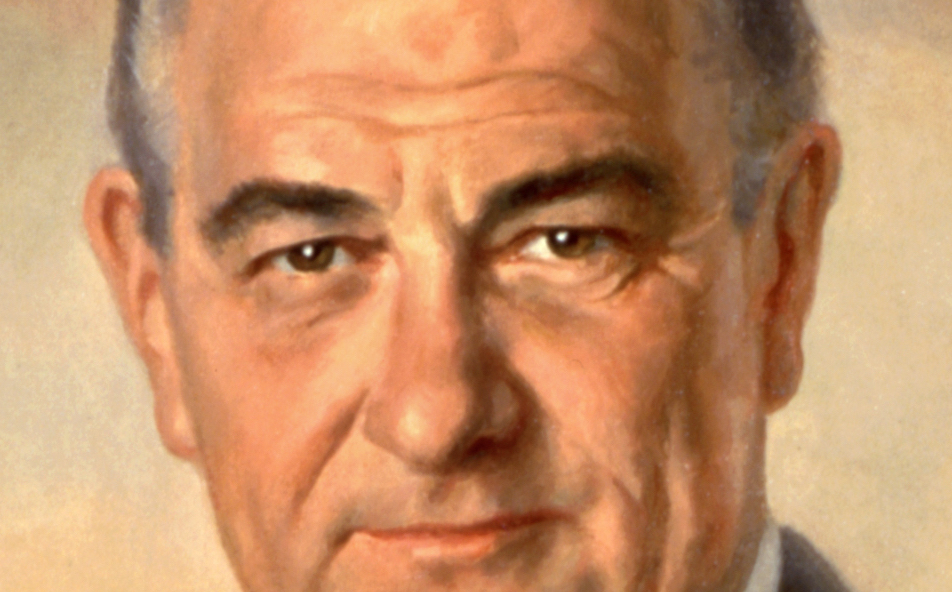

How about the first of three Texans who have served in the White House, Lyndon Johnson? His name probably doesn’t immediately pop up amid thoughts of climate change and global warming.

However, as the news website The Daily Climate recently reported, it was 50 years ago in 1965 that Johnson made “the first presidential mention of the environmental risk of carbon dioxide pollution from fossil fuels.”

It came in a special message to Congress in which Johnson, according to The Daily Climate’s retrospective article, “warned about build-up of the invisible air pollutant that scientists recognize today as the primary contributor to global warming.”

“Air pollution is no longer confined to isolated places,” said Johnson less than three weeks after his 1965 inauguration. “This generation has altered the composition of the atmosphere on a global scale through radioactive materials and a steady increase in carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels.”

The speech mainly focused on all-too-visible pollution of land and waterways, including roadside auto graveyards, strip mine sites, and soot pollution that had marred even the White House.

Within the year, Johnson would sign six new environmental laws during a period better remembered for the strife that led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the escalation of the Vietnam War. Johnson also that year established a dozen new national monuments, historic sites, and recreation areas; and submitted a draft nuclear non-proliferation treaty to the United Nations.

Given Johnson’s little-remembered place in history with regard to manmade climate change, it seems fitting that a recent project at the University of Texas institution that was named for him, the LBJ School of Public Affairs, involved a group of papers by graduate students outlining ideas for dealing with the issue.

They include policy recommendations for the U.S., European Union and 12 other nations. The papers, according to U.T.’s Energy Institute, identify “some of the important barriers and opportunities to mitigate greenhouse gases in the world’s major economies as scientists and other researchers across the globe ready for the next round of climate negotiations.”

Those negotiations, scheduled to take place in Paris in November and December, will be the latest follow-up talks to the climate convention that the first President Bush signed 23 years ago.

Without mandates for emission reductions that a resulting treaty might yield, the UT students’ recommendations may have to rely on nation-by-nation policy initiatives if they’re to be implemented.

– Bill Dawson