By Bill Dawson and Greg Harman

By Bill Dawson and Greg Harman

The impending demise of Denton’s brief ban on fracking, overwhelmingly adopted by voters in the North Texas college town last November, is a potent example of the oil and gas industry’s continuing primacy in the state and reminder that those who challenge it risk forceful political blowback.

At the same time, the fate of the Denton ban suggests that climate activists, campaigning internationally against fossil fuels, were overoptimistic or simply trying to rally their forces when they hailed it – a grassroots win in Texas, of all places – as a possible precursor of more local victories, here and beyond.

The Denton ban on fracking will end with Gov. Greg Abbott’s signature of a bill that the state Senate passed earlier this month, just a couple of weeks after it won similarly lopsided, bipartisan House approval. Any future bans on the controversial drilling method by other Texas cities will be forbidden by the measure, HB 40. Abbott, whose approval of the bill was universally expected, confirmed on Monday that he would sign it.

A strong effort to enact such a “ban on fracking bans” was given a good chance of success in this year’s legislative session, given the election victories in November of the anti-regulation Abbott and Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, plus large, philosophically kindred Republican majorities in both the House and Senate.

But critics say the bill that eventually passed – which “expressly pre-empts” local regulation of oil and gas operations in favor of oversight at the Texas Railroad Commission – goes beyond outlawing fracking bans with a big bonus for the oil and industry.

That extra benefit, they say, came in the form of provisions that make cities’ enforcement of rules to protect public safety and health harder, if not impossible in some cases, to carry out.

“It’s a horrible bill,” declared Scott Anderson, an attorney who has led the Environmental Defense Fund’s (EDF) attention to policy issues involving natural gas development issues since 2005 and was formerly an executive of the Texas Independent Producers and Royalty Owners Association (TIPRO), a major oil and gas industry group.

HB 40 was widely known as the “Denton fracking bill,” but Anderson told Texas Climate News that overturning the Denton prohibition and banning other cities’ potential bans on fracking is actually “one of the smaller impacts” it will have.

The bill, he said, additionally “upends tens of thousands of regulations by dozens of cities,” and Denton voters’ fracking ban simply provided “a convenient excuse” for the oil and gas industry to pursue a broader legislative goal of reducing its regulatory burden across the state.

Even before the House passed HB 40, but after committee approval foretold the eventual outcome, EDF announced that it was filing three petitions with the Railroad Commission, seeking new state regulations to replace local ordinances “that will be hampered or eliminated” by the bill.

Such ordinances, the organization said, have historically “protect(ed) public health, safety and property from oil and gas development” through rules covering such things as minimum distances of drilling rigs from schools and hospitals, limits on truck traffic and noise restrictions.

It cited a number of local rules that “would need to be replacement regulations at the state level,” including “truck traffic routing and time limits within city boundaries to minimize impacts on adjacent land uses; requirements for installation, maintenance and activation of subsurface shut-off valves that control well flow in the event of catastrophic damage at the surface from hurricanes; (and) disclosure of pipeline and gathering-system locations to allow cities to plan and provide emergency responses and delegation of permitting authority.”

EDF’s harsh criticism of HB 40 and its damage-control effort at the Railroad Commission are a telling sign of the magnitude of the industry victory that the bill’s passage represents.

Green vs. green

Some may also find it ironic that it’s EDF, instead of some other environmental organization, trying to salvage regulatory protections at the state agency – development that illuminates the evolution of the natural gas and fracking issue within the broader discussion of what to do about manmade climate change.

Contrary to what some casual observers might think, all environmental groups are not always on the same page, in terms of either tactics or policy positions. EDF, a national organization with a major staff presence in Austin, is known for its often collaborative, bridge-building interactions with industry and does not share the same strong opposition to fracking and natural gas that many other environmentalists, including those at other major organizations, have adopted in recent years.

Natural gas is the principal fuel produced by fracking the Barnett Shale region of North Texas, and the fracking-enabled natural gas boom that began there in the 2000s inspired the expansion of fracking in other parts of the country. In step with that trend came growing citizen complaints in affected areas.

As that happened, many environmentalists and climate campaigners increasingly grew hostile to both fracking and natural gas, despite its lower emissions of conventional pollutants and climate-disrupting carbon dioxide than those that occur when other fossil fuels are burned.

Reasons for this increasing opposition included fracking’s local impacts, such as threats to water and air quality; concern that more natural gas production could slow a transition to cleaner, renewable forms of energy; and worries that increased use of natural gas would bring increased leakage of methane, an especially potent greenhouse gas, during production and distribution.

Amid a variety of research findings on the subject in recent years, people voicing this last concern argue that methane leaks could offset any climate benefit that might accrue from substituting natural gas for dirtier fossil fuels, particularly for coal in power plants. Questions about methane have figured in shifting positions of many environmentalists regarding natural gas.

For example, the Worldwatch Institute, a sustainability-focused think tank in Washington, concluded in a research report on natural gas in 2010 that “renewable energy, energy efficiency, and natural gas hold the key to a low-carbon future.”

Worldwatch released a new analysis of the shale gas boom last month, however, which came to a more pessimistic conclusion:

“The shift in the United States from coal to natural gas for power generation has helped to reduce domestic greenhouse gas emissions in the short term. But the long-term, global benefit of this reduction is dubious, as fracking releases large quantities of methane—a more potent contributor to atmospheric warming than carbon dioxide—and because growing amounts of U.S. coal have found their way to export markets.”

Even more striking is the radically changed position of the Sierra Club, which was founded in 1892 and calls itself the nation’s largest grassroots environmental organization.

In 2009, the Wall Street Journal reported that despite growing dissent in some local chapters, the Sierra Club at the national level was “one of natural gas’s biggest boosters,” supporting it, along with other major green groups, as a “bridge fuel” to get past coal and oil to a renewable-energy future.

The Journal added that Carl Pope, then the Sierra Club’s executive director, “has traveled the country promoting natural gas’s environmental benefits, sometimes alongside Aubrey McClendon, chief executive of Chesapeake Energy Corp., one of the biggest U.S. gas companies by production.”

In 2012, Time reported that “between 2007 and 2010 the Sierra Club accepted over $25 million in donations from the gas industry, mostly from Aubrey McClendon, CEO of Chesapeake Energy—one of the biggest gas drilling companies in the U.S. and a firm heavily involved in fracking—to help fund the club’s Beyond Coal campaign.”

Now, the Sierra Club has added a “Beyond Natural Gas” campaign, citing methane concerns among others. “Natural gas is a menace to our air, water, local communities and climate,” the campaign’s website proclaims. “Natural gas is not part of a clean energy future.”

In contrast, EDF continues to argue that natural gas can be a key part of a transition to such a future. However, in light of growing findings about methane leaks it stresses a key proviso, reflected in a blog post last month by the senior manager for natural gas at EDF’s U.S. Climate and Energy Program: “Reducing methane pollution is not only a significant tool to address climate change; it’s also critical for ensuring that natural gas plays a credible role in the planet’s transition to a lower carbon energy system.”

A local vote with statewide ramifications

The Denton ban on fracking was celebrated by climate campaigners elsewhere who are opposed to natural gas as a victory for “direct action against climate change.” But the climate issue never figured prominently in the local debate leading up to the vote by residents. Local organizers of the drive for the ban instead stressed fracking’s impacts on air quality and property values in the city itself, declaring they were not trying to ban fracking everywhere.

Cathy McMullen, a nurse who leads the Denton Drilling Awareness Group that campaigned for the prohibition, was sufficiently encouraged by its victory at the polls, however, to warn industry leaders that they should “listen to concerned citizens” if they want to avoid similar local bans in other cities. It’s evidence of just how quickly the political landscape can shift on such an issue that just five months later, state lawmakers have decreed there will be no such municipal bans in Texas, regardless of voters’ wishes.

Nosebleeds and breathing problems. The near-constant noise of oil and gas drilling and production in residential areas. Even widely circulated videos of flammable water. All helped inspire the fracking ban in Denton.

But before disgruntled residents organized their drive to ban the drilling method outright, they tried for years to temper it.

On one level, it was an extended tussle with competing claims of property rights. Fracking enabled the oil and gas industry to tap previously unreachable deposits, extending its reach across the Barnett Shale and into urban areas including Denton. Besides oil and gas operators, some local residents benefitted because they owned royalty-producing mineral rights. Others organized to protect their health, quality of life and home values against a rash of industrial impacts.

Fracking, formally “hydraulic fracturing,” involves the shattering of deep shale formations with millions of gallons of water and slurries of chemicals to release the oil and gas there.

As the region’s fracking boom progressed, controversy intensified in Denton. The city passed a moratorium on new drilling, tightened local codes and promised to start to measuring air pollution.

But members of the Denton Drilling Awareness Group said the city’s failure to actively monitor air quality moved them – as a last resort, they insisted – to seek the first fracking ban by a Texas city.

“Because the city cannot uphold its public promises to measure fracking pollution – let alone prevent it – we have no option but to protect our health by banning fracking altogether,” McMullen said early last year as signatures were being collected to put the matter on the ballot.

Many expected legal challenges to Denton’s ban. In fact, lawsuits materialized just hours after the vote from both the Texas General Land Office and the Texas Oil and Gas Association. In March, the Republican leadership at the Legislature delivered their proposed response with HB 40 and companion bill SB 1165, respectively submitted by Rep. Drew Darby of San Angelo, chair of the House Energy Resources Committee, and Sen. Troy Fraser of Horseshoe Bay, who chairs the Senate Natural Resources Committee.

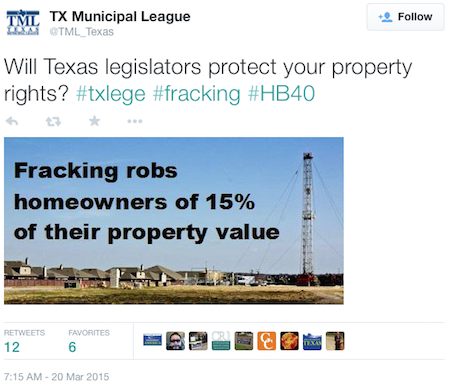

Joining environmentalists in staunch opposition were leaders of various cities and the Texas Municipal League (TML), which represents 1,145 cities across the state.

The Texas Municipal League initially argued forcefully against HB 40

A post on TML’s website, headlined “Oil and gas industry goes nuclear against homeowners,” reflected the depth of that organization’s unhappiness. It said the industry-backed HB 40 and SB 1165 would go far beyond the expected effort to block city bans on fracking and nullify local restrictions such as setback rules, thereby allowing companies to drill “right next to homes, day care centers, churches or hospitals.”

TML’s post charged that the oil and gas industry had “gotten greedy and see an opportunity to pursue a ‘scorched earth’ strategy to wipe out nearly every city regulation.”

A compromise with dissenters

Eventually, however, Darby crafted a compromise between TML and the principal industry backer of his HB 40, the Texas Oil & Gas Association (TXOGA). Both organizations agreed to “support or be neutral to” the revised version, Darby vowed to resist further amendments, and the bill easily passed the House and then the Senate without changes beyond those he had negotiated.

As approved by both chambers, the bill states that regulation of subsurface oil and gas activity (including but not limited to fracking) is the exclusive territory of the state and that local governments can oversee such aboveground matters as emergency response, traffic, related lights and noise, as well as set “reasonable” setback requirements. However, the measure stipulates that local restrictions would have to be “commercially reasonable” and could not prohibit activities by any “reasonably prudent operator.”

The Texas Oil & Gas Association stressed fossil fuels’ benefits in the debate over HB 40

Following the Senate vote, TXOGA president Todd Staples issued a statement praising the bill, saying it would “continue the 100-year history of cooperation between Texans, their communities and oil and natural gas operators.” He added that it is “a fair bill that balances local control and property rights.”

TML, in one of its periodic legislative updates for member cities, said the compromise version was “unnecessary” but the best deal cities could achieve under the circumstances:

“If the deal weren’t in place, and given the political makeup of the Texas House and Senate, it’s nearly certain that further amendments to the bill would make it worse instead of better (most likely worse than the originally-filed version). Some committee members where the bill and its companion were heard expressed frustration that city authority wasn’t completely preempted.

The TML update listed “four significant ways” the compromise made the bill better:

- A list of items that cities can still regulate, with setbacks “a key component because the original version of the bill likely prevented them.”

- Letting cities regulate aboveground matters “related to” oil and gas activities, instead of the “prohibitively restrictive” original language, “incident to.”

- An “objective standard” to determine which city regulations are “commercially reasonable,” instead of leaving that question up to oil and gas companies’ own “subjective assessment.”

- A presumption that an ordinance is “commercially reasonable” if it has allowed oil and gas activity for at least five years.

TML said it had concluded that “better than 80 percent of what most cities regulate under current ordinances will be protected” under the deal brokered by Darby. There are strong dissenters among city leaders and backers of city regulations, however.

For instance, the city of Dallas, which has some of the nation’s toughest regulations on fracking that some believe serve as a de facto ban, remains staunchly opposed to the compromise version.

“I appreciate the beneficial changes that have been made to the bill in recent weeks, but my fear is we end up with a cookie-cutter approach that does not take into consideration individual city needs and differences,” Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings said in a prepared statement.

A common refrain of HB 40’s critics is that its limitations on cities’ authority could still restrict their ability to establish setbacks that would effectively create buffer zones around drilling sites to ensure public health and safety.

Jim Jeffers, city manager of Nacogdoches, wrote to that area’s state senator, Republican Robert Nichols, saying his city and many others in East Texas “would love to have more oil and gas production within their city limits due to increased tax value,” but Nacogdoches remained opposed to the revised HB 40 because of its “encroachment” on local regulations that “simply protect the public health, safety and welfare.”

The editorial board of The Eagle, the daily newspaper serving Bryan-College Station, also had a more pessimistic view than TML regarding the level of municipal authority that will survive once HB 40 (which it called “a bad, bad bill”) becomes law. In an editorial last month, the board echoed a decades-old allegation that the oil and gas industry “controls” the Railroad Commission, the principal state agency assigned to regulate it, and added that “cities will be left impotent” with regard to drilling, which will be able to occur “pretty much any place an operator chooses.”

A Denton councilman drew attention to a lightning-ignited well fire

Sarcastically expressing similar distrust of state officials to regulate drilling adequately, Kevin Roden, a member of Denton’s city council who supported the city’s fracking ban, took to Twitter on May 7 when lightning turned a Denton gas well for several hours into what the Dallas Business Journal called “a raging inferno”:

“Hey @TXlege and @GregAbbott_TX: thanks for all the great regulation at the state level.”

Cities and their environmentalist allies may at least have been successful enough in inserting safety concerns into the debate over HB 40 that, even in defeat, they prompted a passing nod to that issue from the industry.

In his statement following Senate passage of the bill, TXOGA’s Staples said it will “keep Texas communities safe and our economy strong.” The Texas oil and gas industry has “a long track record for safe and responsible production,” he added, while it “pays billions of dollars” in taxes “that directly fund schools, roads and essentially services.”

TIPRO’s president, Ed Longanecker, issued a statement upon the Senate vote that dealt solely with economics, however, in making an argument that state-level regulation is preferable to local control:

“Our greatest priority as an industry is the need for regulatory certainty in our operations. A patchwork effect of local ordinances creating inconsistent regulations, some of which are intentionally onerous in nature, is the wrong path forward, and if left unchecked, could negatively impact investment, tax revenue, employment, and lead to additional legal challenges over property rights.”

Just as some city officials were displeased by TML’s stance, not everyone at TIPRO was pleased by HB 40, however. The Texas Energy Report’s Polly Ross Hughes reported that attorney Rex H. White Jr., a past chairman and current board member of that industry organization and a veteran of 47 years of legal experience in the field, believed the bill would “threaten the traditional authority of cities to safeguard [their] citizens” and was telling lawmakers that a ban on municipal fracking bans was enough to protect companies’ interests.

Local control: Protecting the public or threatening liberty?

The legislative effort to restrict local regulation of fracking has been playing in the context of a broader debate over local regulatory authority and is in step with Abbott’s aspirations for the 2015 legislative session.

In January, before his inauguration, Abbott rolled out some of his priorities for the session. High on that list was limiting the power of local governments. Speaking before a group highly sympathetic to the message – the Austin-based Texas Public Policy Foundation (TPPF), a conservative think tank heavily funded by the libertarian-leaning Koch brothers’ Koch Industries and other business and industry interests – the then-governor-elect decried what he called patchwork regulations that were fast turning the “Texas Miracle” of nation-leading economic growth into the “California Nightmare.”

“This is being done at the city level with (plastic) bag bans, fracking bans, tree-cutting bans,” he said.

Before agreeing to abandon its opposition to HB 40, the Municipal League listed it as just one of a slew of bills submitted this session that would weaken local controls by reserving those areas for the state government.

On its Big Government Index list, the TML includes bills submitted by state lawmakers that would take away cities’ ability to ban plastic bags; prohibit the open carry of guns on city property; regulate agricultural products, including raw milk, as well as stun guns, knives, and pepper spray; or hire lobbyists. As of Monday only one of those bills – HB 40 – had been passed by both the House and Senate and sent to the governor, according to the TML Index.

Even so, the House last week passed another bill inspired by Denton citizens’ fracking referendum. HB 2595 by Republican Rep. Jim Keffer of Eastland would prohibit presenting a municipal ballot item “requesting the enactment or repeal of an ordinance or charter provision if it would restrict the right of any person to use or access the person’s private property for economic gain.”

Environmentalists argue that the bill would prevent voters from having a direct say on plans for projects like landfills and reservoirs, but Keffer said it would only prohibit referendums affecting property uses, not city-council-adopted ordinances themselves, the Dallas Morning News reported.

Surrounding the debates on specific bills, competing advocates have sought to position themselves as the true champions of long-held Texas traditions.

The free-market-promoting TPPF released a policy paper on the fracking issue in March, appealing to Texas conservatives’ frequent hostility to federal regulations:

“Government power held closer to the people often makes that power more responsive. However, local governments and municipalities through laws and ordinances, are just as adept at violating our liberty protected in the Constitution as the federal government. Local control is not the primary governing principle in our state or our country – liberty is.”

Against such arguments, proponents of local regulatory authority have countered that restricting cities’ authority to protect public health and quality of life would reverse a long-established, widespread Texas practice.

In an April 30 letter to Darby and Fraser, 15 city and county officials – including the mayor of Wichita Falls and the county judges of Travis and El Paso counties – noted that more than 300 Texas cities have ordinances restricting oil and gas drilling:

“The notion that our communities have the right to control activities which threaten public health or the quality of life of their residents has a long tradition in Texas law. This principle is the basis of common health ordinances and local land use rules, including zoning, which often involve trade-offs with property rights and other interests.”

+++++

Bill Dawson is the editor of Texas Climate News. Greg Harman is an independent journalist based in San Antonio.