With a coastline extending hundreds of miles from Louisiana to Mexico, Texas faces a challenging future as human-caused climate change brings what scientists project will be escalating rates of sea-level rise.

Researchers are increasingly training their attention on what that may mean. A couple of recently published, nationwide studies by scientists based in New Jersey and California provide graphic portrayals of the threats that sea-level rise poses to populated areas in Texas and other states.

Looking ahead, more in-depth mapping and evaluation of how rising seas could affect Houston and nearby areas on the upper Texas coast, plus “tools to address this critical issue,” will be forthcoming from a recently announced project being launched by researchers at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi.

Texas cities and “locked-in” sea-level rise

Climate Central, a news and research organization based in Princeton, N.J., last month published a scientific study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and related materials on its own website, listing coastal cities at risk of significant inundation because of sea-level rise that is being “locked in” by increasing emissions of greenhouse gases.

Ben Straus, the Climate Central scientist who authored the paper, explained in an article on the Climate Central website that his study had analyzed the implications for the U.S. of another study by an international team of scientists that found for every degree Fahrenheit that the earth’s average temperature rises because of accumulating greenhouse emissions, global average sea level will rise by about 4.2 feet “in the long run.”

To begin with, it appears that the amount of carbon pollution to date has already locked in more than 4 feet of sea level rise past today’s levels. That is enough, at high tide, to submerge more than half of today’s population in 316 coastal cities and towns (home to 3.6 million) in the lower 48 states.

By the end of this century, if global climate emissions continue to increase, that may lock in 23 feet of sea level rise, and threaten 1,429 municipalities that would be mostly submerged at high tide. Those cities have a total population of 18 million. But under a very low emissions scenario, our sea level rise commitment might be limited to about 7.5 feet, which would threaten 555 coastal municipalities: some 900 fewer communities than in the higher-emissions scenario.

[…]

If we call a place “threatened” when at least half of today’s population lives below the locked-in future high tide line, then by 2100, under the current emissions trend, more than 100 cities and towns would be threatened in each of these states.

Nationally, the largest threatened cities at this level are Miami, Virginia Beach, Va., Sacramento, Calif., and Jacksonville, Fla.

If we choose 25 percent instead of 50 percent as the threat threshold, the lists all increase, and would include major cities like Boston, Long Beach, Calif., and New York City. The lists shrink if we choose 100 percent as the threshold for calling a community “threatened.”

Using a “threat threshold” defined as 25 percent of a city’s or town’s population below sea level, the interactive graphic accompanying Straus’s article (above) produces projected outcomes for Texas including these:

- By 2020, the current emissions trend yields a “committed” or “locked-in” sea-level rise of 6 feet, 7 inches – enough to inundate 25 percent of the population in 23 Texas cities and towns with a total current population of more than 155,000. The largest are Bayou Vista, Bolivar Peninsula, Freeport, Galveston, Groves, Laguna Vista, Port Aransas, Port Arthur, Port O’Connor and South Padre Island.

- By 2100, the current emissions trend leads to “locked-in” sea-level rise of 23 feet, 1 inch, enough eventually to flood areas inhabited now by 25 percent of the inhabitants of 103 cities and towns with total current population of about 1.36 million. The largest are Baytown, Beaumont, Brownsville, Corpus Christi, Friendswood, Galveston, La Porte, League City, Port Arthur and Texas City.

- Sixteen Texas cities and town qualify in Straus’s study as “threatened” if “threat threshold” is defined as 100 percent of the current population is below a future sea level that’s “locked in” at the current emission trend by 2100. The largest: Bayou Vista, Groves, Laguna Heights, Oyster Creek, Richwood, San Leon, Seadrift, Taylor Lake Village and West Orange.

Straus noted that neither the international team’s study nor his own calculations based on their research address “the big question” of how quickly sea levels propelled by a warming climate will rise to those “locked-in” levels.

The international team put an upper limit of 2,000 years on the period when that would happen, he wrote, but added that “our sea-level rise commitment [the “locked-in” increase due to manmade climate change] may be realized well before two millennia from now,” since “middle-of-the road projections point to rates in the vicinity of 5 feet per century by 2100.”

Natural protection against rising seas

In another recently published study – conducted by the Natural Capital Project, based at California’s Stanford University, and the non-profit Nature Conservancy – researchers used computer modeling to map natural habitats to identify places where those ecosystems protect human populations against impacts projected to increase due to climate change.

“The main question we were asking with this analysis was where do coastal ecosystems like wetlands, coastal forests and oyster reefs have the potential to reduce risk to people and property from sea-level rise and storms,” Katie Arkema of the Natural Capital Project, who led the research effort, told Texas Climate News.

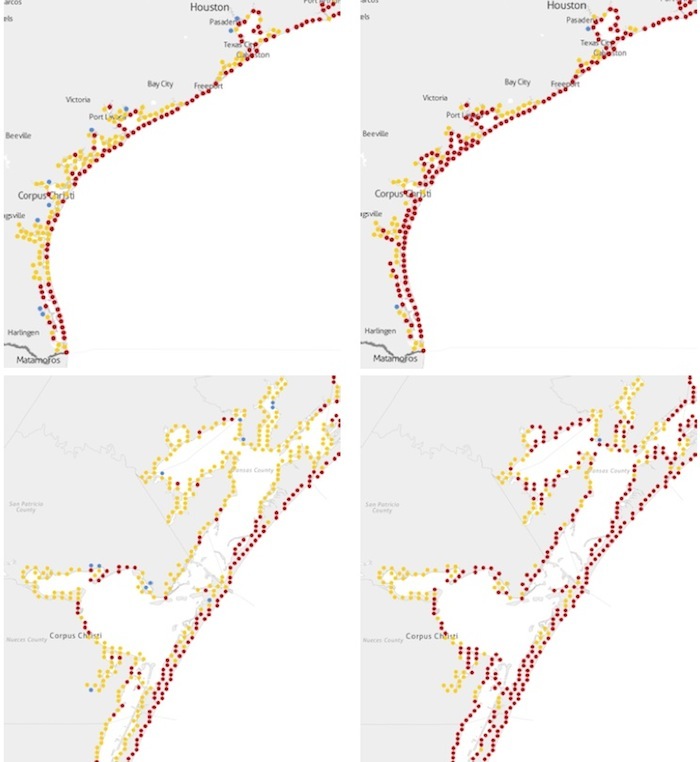

The resulting study was published last month in the journal Nature Climate Change. To produce those findings, the research team combined information about coastal habitats, human habitation (identifying areas with “vulnerable populations,” such as poor people and the elderly), property values and information about exposure to storms and sea-level rise within 1 kilometer of the shoreline. Five future sea-level-rise scenarios were analyzed in combination with two ecosystem scenarios – one in which natural habitats are preserved and one in which they disappear due to human development or climate change.

Announcing the research results, the Natural Capital Project said:

The paper’s findings are relevant at a time when U.S. coastal planners are grappling to manage shorelines for rising sea levels, intensifying erosion, and storm events. The devastating and costly impacts of Hurricane Sandy highlight the need for such analyses to inform strategies for enhancing resilience of coastal communities to shoreline erosion and inundation. Arkema et. al present the first national map of risk-reduction due to coastal habitats, suggesting areas where investing in coastal ecosystems is a critical component of coastal defense and climate adaptation planning.

In Texas, nearly 40,000 people live in “high-risk areas” that are now protected, or where hazards are at least reduced, by coastal ecosystems, Arkema said. Protected property in those areas totals about $2.5 billion in current value, she said.

In the sea-level-rise scenario assuming the second-highest increase among the five scenarios studied, slightly more than 100,000 near-shoreline Texas residents were projected to be at “high risk” in 2100 with habitats intact, and about 130,000 residents if they are “lost owing to climate change or human impacts.”

One finding about Texas that struck the researchers as “particularly interesting” was the estimate that about 1,000 poor families, especially concentrated along the southern part of the state’s coastline, live in high-risk areas protected by natural ecosystems, Arkema said.

“That’s not the top number across the U.S., but is quite high in proportion to the total [at-risk] population,” she said.

An interactive map illustrating the research findings can be accessed here. Some of that map’s results show how hazards increase with the loss of ecosystems’ protective functions along the Texas coast:

In each pair of maps above, the map on the left displays the "hazard index" values that researchers calculated at different locations with a current rate of sea-level rise and habitat intact. Each map on the right shows the projected situation in 2100 in a "high" sea-level rise scenario without habitat. Blue dots represent the lowest hazard index ratings, yellow dots are for medium values, and red dots indicate the highest hazard numbers. (Source: Natural Capital Project)

[Previously in Texas Climate News: An in-depth interview with Jim Blackburn, a Houston environmental attorney and Rice University professor, about a Rice hurricane-preparedness project’s partnership with the Natural Capital Project.]

Assessing the Houston region’s risks

The Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies at Texas A&M-Corpus Christi recently announced that it would undertake “a ground-breaking project to map and evaluate the effects of sea level rise on the upper Texas coast and develop tools to address this critical issue.”

The institute, which has previously carried out sea-level-rise modeling for Galveston, Mustang and South Padre Islands and sea-level-rise research in the Galveston Bay region, “will assess the impacts of sea-level rise on the greater Houston area in order to acquire the knowledge necessary to mitigate and adapt to higher sea level during the next 50 to 100 years,” the announcement said.

Larry McKinney, a biologist who is Harte’s executive director and was formerly a senior official at the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, described the project’s significance in language that some top Texas officials with contrarian views rejecting the mainstream conclusions of climate science may find at least challenging and possibly annoying:

“If you want to stick your head in the sand about the implications of climate change along the upper Texas coast, you are likely to drown. Climate change and land subsidence have effectively doubled the relative sea-level rise along the upper coast and we have millions, even billions, of dollars in natural and manmade infrastructure at risk. If we do not effectively deal with it, we will pay the price – either over time or when the next hurricane hits. That is fact, not opinion.”

Flavius Killebrew, president/CEO of Texas A&M-Corpus Christi, said he was proud that the university “can provide the necessary knowledge to make Texas and the entire Gulf Coast better prepared; not just years from now but for decades to come.”

The institute’s announcement added these details about the project, which will enlist the expertise of a team of three endowed chairs at the institute:

The program is the first of its kind in Texas to project changes to the environment caused by sea level rise and also examine the socio-economic impacts and public policy options for living with a rising sea. The natural and built environments of the greater Houston area are part of a low-lying coastal plain that is undergoing sea-level rise which is causing critical coastal environments, such as coastal wetlands, to migrate or convert to open water. Since 1908, the tide gauge at Pier 21 on Galveston Island has recorded a rise in relative sea level of about two feet. Roughly one foot of this rise is due to a global increase in ocean water volume caused by climate change with the remainder caused by local land subsidence. The amount of relative sea-level rise across the greater Houston area varies because of differences in how much the land is subsiding. Land subsidence has been and is expected to remain an important component of relative sea-level rise during the next 100 years, and the global component of the rate of sea-level rise is expected to increase.

This phenomenon makes Houston and the surrounding areas more vulnerable to damage from hurricanes and other environmental changes. It also creates a concern for the fast-growing population in the Upper Texas Coastal region who may find their homes and businesses literally at the water’s edge. The study will assess the growing vulnerability of Houston and its surrounding counties to the adverse consequences of sea level rise.

The research is being funded by a $790,000 grant from Houston Endowment, a leading philanthropy that has been the major financial supporter of Texas Climate News since this magazine’s launch in 2008.

– Bill Dawson

+++++

Editor’s note: Texas Climate News is published by the non-profit, non-partisan Houston Advanced Research Center. TCN’s editors and writers are not HARC employees and make all editorial decisions independently, without direction or influence from HARC, its partners and funders.

Image credits: Interactive graphic – Climate Central; Maps – Natural Capital Project