“Ain’t no more cane on the Brazos,” inmates at Texas prison farms chanted in a 19th century work song perpetuated by latter-day singers including Lead Belly, Bob Dylan and Lyle Lovett.

Employing a little poetic license for exaggeration, a singer of topical songs today might modify that lyric to “Ain’t no more water in the Brazos” in a nod to just one of the recent news items detailing the once-again expanding drought that blankets most of Texas.

The inspiration could be a story in the Texas Tribune, which reported the possibility of water shortages in Galveston County. Most of the water supply there comes from the Gulf Coast Water Authority.

The Tribune explained the situation:

“The GCWA holds water rights to more than 450 acre-feet of water from the Brazos River, but it began running out of water on June 14, said general manager Ivan Langford.

“’The river, in essence, ran dry,” he said.

If public water-supply systems in Galveston County impose tougher water-use restrictions than are already in place as a result of reduced flows in the Brazos, they’ll hardly be alone in adapting to evolving drought conditions.

In the Central Texas city of Brownwood, for instance, the Brownwood News reported that stricter water-use limits appeared likely:

The Brown County Water Improvement District #1 (BCWID) is sticking with Stage 3 water restrictions for another month, but encouraged the public to conserve in outdoor watering as Stage 4 restrictions loom as the level at Lake Brownwood continues to decline.

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality last week reported that of 4,663 such public water systems across Texas, the number with some level of water-use restrictions in effect has risen to 988, with mandatory rules at 665 systems and voluntary measures being urged at another 323.

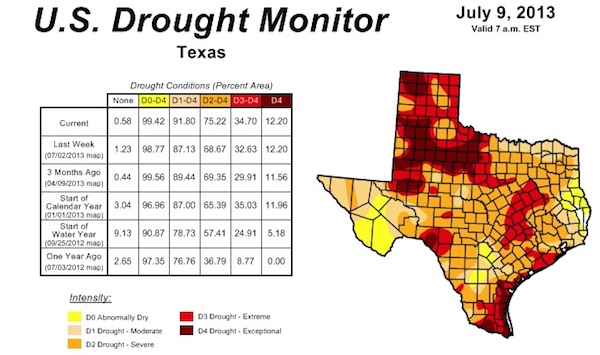

A glance at the latest U.S. Drought Monitor maps and statistics, posted last Thursday, shows the reason for the large number of restrictions.

Except for a tiny sliver of white (meaning no abnormally dry or drought conditions) in Southeast Texas, the entire state was in colors indicating drought conditions of varying severity (91.8 percent) or the less-severe “abnormally dry” category (7.6 percent).

A year ago, about 20.6 percent of the state was abnormally dry, while 76.7 percent was in some level of drought.

The effects are being manifested in various ways, none of which should come as a surprise to Texans familiar with drought and its impact as the record-breaking dry spell of 2011 has dragged on:

Wildfires

The state experienced its worst wildfire season on record in 2011, with the most severe destruction occurring in Bastrop County, where more than 1,600 homes burned.

Austin’s KEYE reported Friday on a worrisome rash of brush fires in the same county that was conjuring unhappy memories of the 2011 conflagration.

County deputies adopted a no-leniency stance with regard to violations of the local burn ban, the television station reported, quoting Bastrop Sheriff Terry Pickering: “We are very vulnerable right now for another wildfire.”

Concerns about fires due to dry conditions were reported in other parts of the state, as well.

“North Texas is so dry that grass fires can easily ignite, and temperatures climbing past 100 won’t help,” the Fort Worth Star-Telegram reported last week, attributing the warning to weather forecasters.

Part of Texas’ exceptional heat in 2011, which created conditions conducive for that year’s wildfires, has been credited by climate scientists to manmade global warming.

Now, there’s new scientific evidence suggesting wildfires may themselves add to that human-caused warming. The Los Angeles Times reported last week that researchers at New Mexico’s Los Alamos National Laboratory had determined that wildfires “may be warming Earth’s atmosphere far more than previously thought.”

Scientists scoured the terrain where a major wildfire occurred near the laboratory in 2011, collecting and analyzing particles created in the blaze.

The newspaper reported:

The Los Alamos team identified tar balls – spherical, carbon-based particles – that are 10 times more prevalent than soot particles, and can boost the heating effect of wildfire emissions, according to the study, published last week in the journal Nature Communications.

“We provided the data that shows that current estimates, which are close to zero or show a very slight warming, are incorrect and the warming will be higher,” [researcher Manvendra] Dubey said. “We are confident this will change the results and show that fire emissions will have a tendency to warm.”

Close examination of soot also showed these particles were sheathed by organic coatings that “act like a lens to focus sunlight and amplify the sunlight that soot absorbs,” Dubey said.

Water conflicts

Data maintained by the Texas Water Development Board indicate that reservoir levels around the state, which had stayed about the same for several months, have started edging downward.

Taken together, all monitored water-supply reservoirs were 63.9 percent full on Sunday – slightly down from the 66.4-percent level measured one and three months ago and substantially lower than the 73.5-percent cumulative level that was measured one year ago.

Conflicts over allocation of scarce Colorado River water, stored in Central Texas’ Highland Lakes reservoirs, are a chronic matter, stemming from competition among users including lakeside residents and businesses around those reservoirs, the city of Austin and downstream agricultural interests. Because of low river levels during the current drought, Lower Colorado River Authority (LCRA) officials have withheld water from downstream rice farmers in 2012 and again this year.

Now, farmers aren’t the only downstream users complaining about low flows on the river below Austin.

The Austin American-Statesman last week reported that Mark Rose, general manager of Bluebonnet Electric Cooperative, said the Colorado in Bastrop County “is rife with algae, impeding boaters and raising questions about the quality of the water.”

The newspaper quoted Rose:

“There are parts of the river where people on canoes or kayaks can’t even get through,” he said. “This is much bigger than just the river. It’s about recreation. There is a $50 million park system along the river and many businesses that operate along the river.”

The LCRA, in one of its regular drought updates, reported on its website that “heavy growth of aquatic weeds downstream of Austin is skewing the readings of some stream gauges, making it appear that there is more water flowing in the Colorado River than there actually is.”

The agency explained:

Water weeds commonly grow in the river during summer, but this year is the worst in modern memory. One factor causing the growth is that because of the severe drought LCRA has withheld Highland Lakes water from most downstream farmers in 2013 for the second year in a row. As a result, there is relatively little water flowing in the river this year, which makes it easier for water weeds to grow. A strong steady flow of water has a scouring effect on the river and makes it more difficult for water weeds to grow.

Meanwhile, USA Today, in one of a continuing series of articles on the current effects of climate change across the country, reported on conflicts over groundwater as drought grips Texas amid a gas-production boom in some parts of the state:

“Climate change is likely prolonging the duration and severity of naturally occurring drought in the Southwest,” says Martin Hoerling, a research meteorologist at theNational Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. He says the main cause of U.S. drought today is a lack of rainfall, but by century’s end, the key culprit might be higher temperatures.

Texas, prone to drought, is particularly vulnerable. Its supply of water is shrinking while its demand for water is rising amid a boom in population and fossil fuel production. In a process known as hydraulic fracturing or fracking, huge amounts of water are blasted underground to break apart rock and retrieve oil or gas trapped inside.

So conflicts are flaring between frackers, who are giving what landowners call “mailbox money” for the right to tap their wells, and residents whose wells are running dry. Tiffs have arisen even within families, as some take the money and others don’t. Much of Texas fracking is done in the northern Barnett Shale near Fort Worth and the southern Eagle Ford Shale.

Agriculture

An article in the Dallas Morning News, reporting on an upcoming Texas A&M University conference on the cattle industry, said workshops will include discussions pertinent to aspiring newcomers to the field including one on “introductory cattle production” and another on “retiring to ranching.”

There was also this cautionary note for would-be cattle ranchers mindful of the extra challenges posed by the possibility of a years-long drought that some climate experts have warned about: “Texas, which had just over 4 million beef cows on Jan. 1, has lost more than 1 million beef cows over the last three years because of drought, a 22 percent decline.”

Drought-driven decisions to withhold water from rice farmers in Southeast Texas will also affect wildlife species that use those same fields, the Houston Chronicle reported:

Rice farms are a focus of attention in the Texas drought, and not without reason. Tens of thousands of acres across the state will be out of production this year because of the abnormally dry conditions.

But fewer fields flooded for the thirsty crop also mean fewer places for ducks, geese and other migratory birds to eat and roost during their winter sojourn. In Texas, rice fields have replaced the birds’ favored wetlands, which are rapidly being lost to development.

The Associated Press reported recently on the agricultural situation in the Rio Grande Valley of South Texas, where the farm industry depends on water from the river that forms the border between the U.S. and Mexico:

South Texas is in the midst of a years-long drought that is the driest ever recorded here. While swaths of the state have somewhat recovered from the historic dry spell of 2011, farmers in this agriculture-rich region are dealing with massive crop losses in which entire fields have been wiped out.

[…]

The entire region is in severe, extreme or exceptional drought and crop losses are mounting as insurance adjustors travel field to field. Agriculture officials have predicted losses of cotton, corn and grain sorghum crops could double the region’s $50 million lost in 2006, though the claims are still coming in.

Looking upstream on the Rio Grande isn’t reassuring. New Mexico, where snowmelt feeds the river, is itself in an even worse drought than Texas, with practically the entire state shown in the two most severe categories on the latest U.S. Drought Monitor map.

The AP reported last week that prospects for farmers in a region of southern New Mexico, northwest of El Paso, were not good:

Federal water managers on Tuesday warned that the irrigation season for farmers in [New Mexico’s] Lower Rio Grande Valley soon will be over.

The flow between Elephant Butte and Caballo reservoirs ended Monday, meaning the shortest irrigation season in the history of the Rio Grande Project quickly will be coming to an end. The Bureau of Reclamation said no further releases were scheduled, and the Rio Grande south of Elephant Butte was expected to start drying up. “We’re breaking all the records now of the 1950s and the ’60s droughts. It’s just not a good year,” said Gary Esslinger, manager of the Elephant Butte Irrigation District.

[…]

The Rio Grande Project [a federal initiative for irrigation, hydroelectricity, flood control, and inter-basin water transfers] extends from Elephant Butte into Texas. It delivers water to about 280 square miles of farmland in southern New Mexico, West Texas and Mexico, as well as water for municipal and industrial uses by the city of El Paso, Texas.

– Bill Dawson

+++++

[Editor’s note: This story was updated with additional information after it was first posted.]

Image credits: Wikimedia Commons, U.S. Drought Monitor