The whooping crane – the tallest bird in North America and one of the rarest – is the leading symbol of wildlife-conservation efforts in the United States. In 1941, the species' total population had dwindled to 15 cranes, discovered wintering on the Texas coast. The American Birding Association reported a species population of 599 last September, including 278 cranes in the group that migrates 2,500 miles between nesting grounds in Canada's Wood Buffalo National Park and wintering habitat around Texas' San Antonio Bay, north of Corpus Christi.

By Michael Berryhill

In 1991 a blind, cave-dwelling salamander, two species of beetles, an eyeless crustacean and an inch-long fish helped change how Texas manages underground water. Using the federal Endangered Species Act, conservationists won a federal court order to protect these creatures by limiting the amount of water that can be pumped from the Edwards Aquifer.

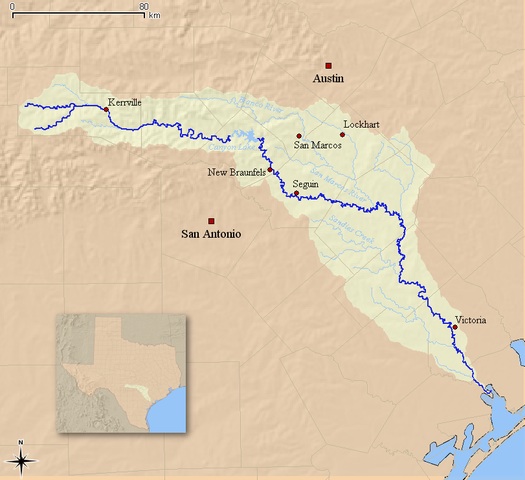

Now a group of conservationists called The Aransas Project (TAP) is using the Endangered Species Act to challenge the management of surface water. The animal in question is no obscure salamander, but the most famous and charismatic animal in North America: the whooping crane. If a federal judge rules in favor of TAP, the way Texas manages the Guadalupe River and its estuary, San Antonio Bay, will be fundamentally changed. The state may have to guarantee that enough freshwater is allowed to flow from the Guadalupe into San Antonio Bay to nourish the blue crab population, the primary food there of the whooping crane.

During the first two weeks of December, experts on the cranes and estuaries argued in federal court about what caused the loss of 23 whooping cranes during their 2008-09 wintering season in Texas. Experts for TAP argued that the birds had died of emaciation and predation brought on by extreme drought. Experts for the Guadalupe Blanco River Authority, which represented the state’s case, said that the birds had survived other droughts and are highly resilient. There was no solid proof that 23 died, since U.S. Fish and Wildlife officials found only four carcasses. The GBRA argued that the cranes are omnivorous and when blue crabs are down, whooping cranes can survive on other foods such as clams, snails, insects, snakes, fiddler crabs and fish as well as plants, including acorns and wolfberries, a wild pepper that favors brackish marshes. The defendants questioned whether whooping cranes need to drink fresh water at all and whether blue crabs need freshwater inflows to reproduce.

A reporter for the Corpus Christi Caller-Times characterized the scientific testimony as tedious. But Judge Janis Graham Jack, who declared that she and her husband were birdwatchers and appreciated the annual $5-million ecotourism business that has grown around the cranes, seemed both sympathetic and skeptical about the testimony. When she learned that U.S. Fish and Wildlife’s most eminent specialist on the cranes was not available as an expert witness for either side because of federal rules, she had him subpoenaed. Before he retired last spring, Tom Stehn spent 29 years managing the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge where the cranes winter, and had made no secret that he thought the cranes deserved some measure of freshwater inflows.

In 2003 he told writer Joe Nick Patoski of the San Antonio Current, “We’d like to see environmental considerations done at an early stage. One of the problems with the Texas Water Plan [the state’s water-supply blueprint] is the environment got short shrift. I bet there weren’t a lot of biologists being talked to. Now they’ll have to prove their case that the project [to take additional water from the Guadalupe River] won’t impact endangered species.”

Judge Jack pressed Stehn about his conviction that the 23 cranes died because of lack of freshwater inflows into the bay. “I just want to make sure they didn’t go to New Mexico or to Antigua for the holidays,” she said.

Stehn explained that unlike most birds, the flock of 260 or so whooping cranes is easy to count. They stake out family territories, usually two, three or at most four birds, and were readily observed during his frequent airplane surveys. Stehn added that while he could only count 23 cranes as missing, he thought that more had probably died because of the drought.

Proving the cause of death of even a few birds is a tough problem. There have been periods of low freshwater inflows when large numbers of cranes did not die. But as drought continues on the Texas coast, more data is accumulating. One crane with a radio collar was found dead in mid-December and its body had been sent for a necropsy.

Human-caused climate change is probably a factor in aggravating the current record drought, according to Texas state climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon, who has said it is likely to last another year because of the La Niña weather pattern and to cause “continued drawdown in water supplies.”

Natural droughts are hard to predict, but Texas faces another drought that is predictable, the one that will be produced by its increasing population. Texas is estimated to grow from 25 million people to 46 million by 2060. In December, the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB) issued a sweeping update of its statewide water plan, which outlines projects estimated to cost $53 billion. That number accounts for less than a quarter of the more than $200 billion worth of infrastructure costs that the TWDB estimates the state needs during the next 50 years. Although state law requires that the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department study the freshwater needs of each Texas bay system, environmentalists have been complaining for several years that the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality and the Water Development Board have not fairly allocated water for the bays in regional water plans that comprise the state plan.

The TWDB explains the allocation of surface water this way:

“When issuing a new water right, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality assigns a priority date, specifies the volume of water that can be used each year, and may allow users to divert or impound the water. Water rights do not guarantee that water will be available, but they are considered property interests that may be bought, sold, or leased. The agency also grants term permits and temporary permits, which do not have priority dates and are not considered property rights. The water rights system works hand in hand with the regional water planning process: the agency may not issue a new water right unless it addresses a water supply need in a manner that is consistent with the regional water plans and the state water plan.

“In general, Texas has very little water remaining for appropriation to new users. In some river basins, water is over appropriated, meaning that the rights already in place amount to more water than is typically available during drought. This lack of ‘new’ surface water makes the work of water planners all the more important. Now more than ever, regional water plans must make efficient use of the water that is available during times of drought.”

Here and there, the TWDB acknowledges environmental issues. In the Water Plan study for Region L, which includes the Guadalupe River and its estuary, San Antonio Bay, the agency states: “Concerns have also been expressed that increased uses of existing water rights may reduce freshwater inflows to bays and estuaries.” But that’s as far as it goes.

The study notes that endangered migratory species, such as the whooping crane, must be protected, but the concern seems to be whether proposed reservoirs might be disruptive: “Reasonable and prudent measures should be taken to avoid and minimize the potential effects of project activities on threatened and endangered species…”

Although the state of Texas has been studying freshwater inflows into the bays since the 1980s, the need for such inflows does not appear in the technical summaries of the TDWB’s regional and statewide plans. In projecting the state’s future water needs, for example, the numbers come in only six categories: municipal, manufacturing, mining, steam-electric, livestock and irrigation. Wildlife does not figure centrally in the regional planning, yet freshwater is essential for the bays’ nurseries, where fish, oysters, shrimp, and crabs spend part of their early lives.

“The only exception in the Region L plan,” its authors state, “comes with regard to the Edwards Aquifer. Development of new water supply sources for Bexar, Comal, and Hays Counties reduces reliance on the Edwards Aquifer during drought thereby contributing to maintenance of spring flow and protection of endangered species. The Regional Water Plan recognizes the on-going efforts of the participants in the Edwards Aquifer Recovery Implementation Program (EARIP) to develop a Habitat Conservation Plan which will help to define the requirements for maintenance of spring flow and protection of endangered species and meet with approval from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.”

A “Recovery Implementation Plan” for the whooping crane, or RIP, to use the federal lingo, is just what The Aransas Project hopes to get the state to agree to. Such a plan requires both sides to negotiate the science and the water planning numbers.

The Edwards Aquifer Plan, for example, guarantees 320,000 acre-feet of water during a drought of record.

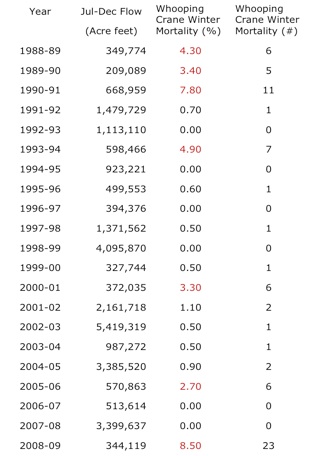

TAP’s expert witness on the correlation of freshwater inflows to whooping crane mortality, Ron Sass of Rice University, used these numbers as evidence:

The red numbers in Sass’s analysis represent the correlation between crane mortality and low inflows. The GBRA lawyers attacked Sass’s numbers and conclusions, which lie at the heart of the plaintiffs’ case.

Lawyers for the Guadalupe Blanco River Authority complained in court that if the Aransas Project wins its case, it would confiscate all the inflow for nature and devastate industry and agriculture in the basin.

But Jim Blackburn, the Houston environmental lawyer and lead attorney for the plaintiffs, contends that argument is nonsense. He has said his hope is that during times of extreme drought that everyone, including the whooping cranes, would get a share of the water.

How much water would be enough to protect the whooping crane and bay ecosystem? TAP’s expert witness on bay salinity, Joseph Trungale, stated in a court deposition: “Changes in inflow as a result of decreased or increased diversions can have a significant impact on salinities. i.e. this analysis shows that 100,000 acre feet difference over several months or a year, can make a difference and significantly raise or lower salinities over large parts of the bay.” GBRA experts on salinity testified that 100,000 acre feet was too little to affect the bay’s salinity.

At the end of the trial in mid-December, Judge Jack told both sides to write their final arguments and present them as briefs later this spring. She said she expected to immerse herself in the trial documents and arguments during the summer and then make a ruling. She also urged both sides to talk about a settlement.

Bill West, the general manager of the GBRA, said there is a possibility of a settlement, but “senior water rights are off the table.” Under state law, the holders of senior water rights are entitled to priority over those who hold junior rights during periods of drought and can take all the water they want. The GBRA, which supplies agricultural, industrial and municipal users, is the largest holder of such rights. TAP argues that it would be fairer if all users, including the bay, got a share of the water during drought.

West said that instead of arguing over water rights, TAP and the GBRA should work toward acquiring and protecting more habitat on the Texas coast for the whooping cranes. The federal goal is to establish a flock of a thousand migrating cranes in the Aransas area. He said that through purchases and conservation easements, the flock’s territory could be expanded further north along Matagorda Bay, and further south along Copano, Corpus Christi and Nueces Bays. “We’re saying that even if the salinity varies, they can accommodate to that if they have adequate habitat.”

Blackburn said he was open to a settlement if it is reasonable, “but this litigation was about water. We think we proved a significant statistical relationship between freshwater inflows and whooping crane mortality.”

If Judge Jack agrees with that science, she can force the GBRA to yield its senior water rights to the cranes and the bay. Such a settlement might win water for San Antonio Bay, but what about the other major Texas estuaries? Advocates for Galveston Bay have complained that in April the state approved such low freshwater inflows that the bay’s wildlife is unprotected. The whooping crane suit could serve as a signal to Texas water planners to include the Texas bays, including their multimillion-dollar fishing and tourism industries, as part of the planning, along with cities, industry and agriculture. Or it could be a signal that in the coming water wars – which increasing droughts and other climate-change impacts that scientists have projected for Texas could undoubtedly aggravate – both planners and conservationists need to lawyer up.

While Judge Jack considers the data for the winter of 2008-09, whooping cranes have returned to their refuge along the shores of the San Antonio Bay-Guadalupe Estuary during Texas’ worst drought on record. The GBRA presented evidence from a $2.1-million study called SAGES, an acronym for the San Antonio Guadalupe Estuarine System. The SAGES study states that crabs reproduce well in high salinities, but crane expert Tom Stehn strongly contested this conclusion, saying it was based on laboratory studies only. The general observation of field biologists is that crabs decline when the salinity of the bays is high. Indeed, the usually robust crab fishery that operates in San Antonio Bay has dwindled to two or three boats going out for half a day. Whooping crane guide Tommy Moore, who watches the cranes almost daily from his boat, says the cranes are not finding crabs, but feeding on dead fish, and he fears that such a diet increases their susceptibility to disease.

The GBRA’s experts contend that whooping cranes are highly adaptable to brackish conditions and may not even need to drink fresh water. Again this contradicts years of field observations in which biologists have seen cranes fly as much as three miles to fresh water to drink. Frequent daily flights for water, they contend, weaken the birds, making them vulnerable to hunger and predators.

At least one family of three whooping cranes flew to the Aransas refuge this fall and found conditions so bad that they flew a couple of hundred miles inland to Granger Lake near Austin. It appears that as many as six cranes may spend the winter there, attracting hundreds of bird watchers who have never seen whoopers so far from their natural territory on the coast.

+++++

Michael Berryhill is chair of journalism at Texas Southern University and a former editor of Texas Parks and Wildlife Magazine.