By Bill Dawson

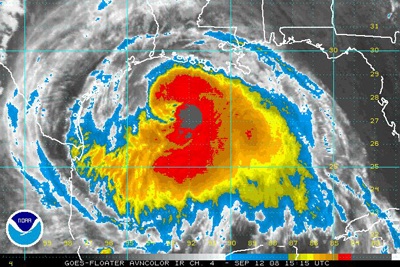

Hurricane Ike

To build or not to build?

More precisely, should the Houston-Galveston region adopt a “structural” or “non-structural” approach to reduce storm surge damage from hurricanes?

That central question hovered over Rice University’s recent Coastal Resilience Symposium, just as it has been at the heart of a community debate since Hurricane Ike brought vast damage to Galveston and the Bolivar Peninsula in 2008.

Instead of taking sides, however, several symposium speakers said the Houston-Galveston region needs to be looking at both structural and non-structural actions to limit its vulnerability to flooding.

Structural methods include things like building levees. Non-structural methods include things like limits on development in surge-prone areas.

Following Ike, it sometimes seemed that the two categories were being presented as opposing alternatives in a polarized dialogue. Two central figures in that debate were among the symposium panelists at Rice.

One was William Merrell, a marine sciences professor at Texas A&M University at Galveston who conceived the Ike Dike – a system of levees and flood gates extending southward, from the top of Bolivar Peninsula to the bottom of Galveston Island. Merrell has said this “coastal barrier” would also protect inland areas including the vast petrochemical complexes near Galveston Bay against surge flooding.

The other was Jim Blackburn, an attorney affiliated with Rice, who has voiced concerns about the Ike Dike’s potential harm to Galveston Bay’s ecosystem. As an alternative to that project, he has suggested replacing some coastline development with a national seashore – one of the coastal units of the National Park System managed for conservation and recreation.

Merrell, Blackburn and others have exchanged back-and-forth arguments in newspaper op-ed columns in recent months.

In January, for instance, Blackburn had a column in the Galveston County Daily News, headlined “National seashore makes more sense than Ike Dike.” He wrote:

If a hurricane buyout fund had been in existence before Ike, there is no doubt that large numbers of homeowners on the Bolivar Peninsula, as well as on the west side of Galveston Bay, would have been willing to have been bought out.

Through time, large green spaces and open beach and bay access areas could be established so that we have recreational access to the Gulf and to Galveston Bay.

Merrell’s responses have included a column in the Galveston newspaper in May, titled “Ike Dike is right solution for bay area.” He argued:

An Ike Dike and a national seashore are not equivalents. A national seashore or any nature area reduces the amount of human-built infrastructure at risk by preventing the presence of infrastructure but does little to suppress surge. The Ike Dike approach significantly suppresses surge for both built and natural areas.

If anyone came to the Rice symposium hoping to experience a live version of that debate, however, they were certainly disappointed.

Instead, the discussion was marked more by broad agreement on some crucial points.

“You have to maintain the ecosystem services in Galveston Bay or we shouldn’t do the [Ike Dike] project.” Merrell said.

For his part, Blackburn said he and colleagues from Rice and other universities and institutions are conducting a study of structural and non-structural options, adding that he agreed with other speakers that the region should be considering “a mix” of the two.

Merrell told the symposium audience that the Ike Dike project could be built with “proven technology,” reiterating the point he has made previously that the Netherlands has ample experience with such coastal-protection systems.

One symposium speaker was Mathijs van Ledden, a Dutch engineer and president of Haskoning, which is involved in a project constructing a surge barrier to protect New Orleans’ Inner Harbor Navigation Canal.

Van Ledden said there is no single “Dutch solution” to block storm surges and urged that structural elements should be regarded as just one element in reducing flood risk.

In any event, climate change should not be ignored in any plans for making coastal areas more resilient in the face of future storms, he said.

Structural projects may be appropriate in some places, while non-structural approaches are more appropriate elsewhere, observed Susan Rees, program manager of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ Mississippi Coastal Improvements Program.

The program which has proposed a plan for reducing hurricane damage to Congress that incorporates structural and non-structural elements, as well as environmental projects.

Ecosystem restoration offers “the biggest bang for the buck,” Rees said.

Sam Brody, associate professor of landscape architecture and urban planning at Texas A&M University, described his research comparing strategies for reducing flood risk by local government entities in Florida and Texas.

Florida employs significantly more non-structural actions – things like zoning rules and development setbacks – than does Texas, he said, adding that a hybrid approach combining non-structural and structural methods is necessary in the Houston-Galveston region.

Phil Berke, a professor of city and regional planning at the University of North Carolina, said he was neither for nor against the Ike Dike, but was skeptical about it.

One concern about the proposal, he said, is that it might have the potential to increase development in high-hazard areas where it offers protection.

Blackburn said his Rice research has revealed that it will be a tough sell to extend even a “modest” non-structural form of protection to prospective home buyers in parts of the Houston-Galveston region – a requirement that sellers inform them if a home is in an official surge evacuation zone.

He said one local official confessed that he doubted he could be reelected if he supported adoption of such a rule.

The symposium was held on the verge of a hurricane season that experts say could be an extremely active one in terms of storm formation.

Adding an even greater sense of urgency to the conference discussions, a report was issued at the event by Rice’s Severe Storm Prediction, Education and Evacuation from Disasters Center, warning that a major hurricane could “devastate the Houston-Galveston region.”

Report conclusions included:

- Roads are inadequate to evacuate the million people living in evacuation zones now, and another half-million residents are expected in those areas by 2035.

- A “major disconnect” exists between the flooding that a major hurricane would cause and the mapping of 100-year floodplains that serve as the basis for flood insurance.

- Most of the water-crossing bridges in the Galveston Bay area – more than 65 percent – may be particularly vulnerable to a strong hurricane, such as Katrina in 2005.

Several days after the symposium, a new nonprofit government corporation, formed to assess how the region can defend against surge flooding, held its second meeting.

Guidry News Service reported that former Harris County Judge Robert Eckels, now president of the six-county Gulf Coast Community Protection and Recovery District, said there is an “emergent consensus” that surge-protection strategies are “at least … worth the review.”

Eckels added that he is “excited about the prospects of providing protection to this upper Texas coast and particularly the coordination between the Houston-Galveston region and the Orange, Jefferson and Sabine basin.”

The Galveston County Daily News reported in April that Galveston County Judge Jim Yarbrough said the district will consider structural projects for protecting the upper Texas coast that extend northward and southward beyond the end points of Merrell’s Ike Dike proposal:

“We are looking at some sort of levee system that would run from the (Texas/Louisiana) state line all the way down the coast to past Freeport.”

[Editor’s note: Merrell holds the George P. Mitchell ’40 chair in marine sciences. Brody holds the George P. Mitchell ’40 chair in sustainable coasts. Mitchell founded the Houston Advanced Research Center, which publishes Texas Climate News.]