James Hansen is perhaps the world’s best-known climate scientist, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York City, and the man who dramatically propelled the subject of global warming to public prominence with his congressional testimony in the late 1980s.

James Hansen is perhaps the world’s best-known climate scientist, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York City, and the man who dramatically propelled the subject of global warming to public prominence with his congressional testimony in the late 1980s.

He was going to speak to Houston’s Progressive Forum on Oct. 29, but had to postpone the engagement until this week because of health matters. As things turned out, Hansen’s rescheduled talk could hardly have come at a more appropriate time.

On Monday, the day of his Houston appearance, the 12-day United Nations Conference on Climate Change had just gotten started in Copenhagen. Negotiators there are trying to forge a binding interntional agreement on reducing greenhouse gases to replace the Kyoto Protocol, which was signed in 1997 and expires in 2012.

On the same day, the Environmental Protection Agency announced its formal conclusion that greenhouse pollutants threaten public health and the environment – a necessary step for regulation of those gases under the federal Clean Air Act. Members of Congress, meanwhile, continue to work on a separate law that would address manmade climate change.

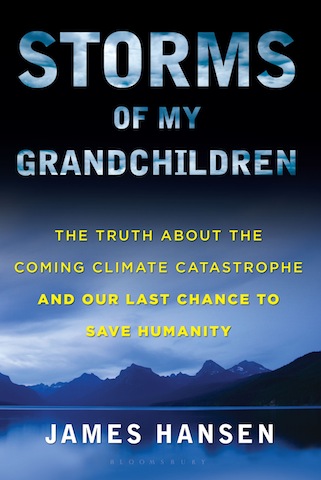

The day after Hansen’s Houston speech, his first book was published – Storms of My Grandchildren: The Truth about the Coming Climate Catastrophe and Our Last Chance to Save Humanity. The title reflects his growing concern about global warming.

In a June 29 profile of Hansen in The New Yorker, Elizabeth Kolbert wrote: “Hansen has now concluded, partly on the basis of his latest modelling efforts and partly on the basis of observations made by other scientists, that the threat of global warming is far greater than he expected.”

The 68-year-old climatologist’s outspoken political activism makes him “an outlier” among climate scientists, Kolbert wrote, and also has “increasingly isolated” him from climate activists who endorse a cap-and-trade policy to reduce emissions. Hansen opposes such an approach, which is central to bills pending in Congress. It would set a cap on carbon dioxide emissions and establish a market for trading emission permits.

In a conversation with Texas Climate News editor Bill Dawson on Monday, prior to his Progressive Forum talk, Hansen explained why he supports a direct carbon tax to reduce greenhouse emissions; described the “climate catastrophe” he expects to unfold without major emission cuts; commented on the disclosure of controversial emails of climate researchers at a British university, and offered a forecast of next year’s global temperature.

Q: You’re perhaps the world’s best-known climate scientist and you’ve been spotlighting the dangers posed by climate change and calling for action to address it for a couple of decades or more now. Recently, you were in the news yet again when you told The Guardian that you hope the Copenhagen conference fails to produce a major, definitive agreement. Could you explain why you feel that way?

A: Of course if they produced an effective one that would be great, but they’re not talking about an effective one, they’re talking about the same old story. They’re talking about the Kyoto Protocol approach, where the core idea is cap and trade with offsets, which practically eliminates the value of any agreements. What they do is set targets, targets that they know in many cases will not be met, and when they are, it will be in terms of offsets, which mean they don’t really reduce their emissions, at least not much, and they buy their way out of it by paying some developing countries to do something that is supposedly useful like preserving a forest or reducing some of their pollution.

But these actually are counter. First of all, it doesn’t reduce the demand. For example, in the case of forests, it does not reduce the demand for wood or for land where you can grow cattle or other foods, or grow foods. Therefore, if you preserve one area of forest, the deforestation and wood harvesting just moves somewhere else. So these things are not really effective.

They won’t face up to the fundamental fact – which should be as plain as the nose on our face – which is that as long as fossil fuels are the cheapest form of energy, they they are going to continue to be used. The reason they’re the cheapest form of energy is they are not made to pay for the damage that they do to human health and the environment and future climate. So the way that you would make them pay is to put a price on carbon emissions, a gradually increasing price so that people have time to adjust their lifestyles and their infrastructure.

So rather than this cap and trade, what I suggest is called fee and dividend. You put a fee on carbon at the mine, so it’s paid by the fossil fuel companies at the mine or at the port of entry where the fossil fuel is imported to the country, and that money should then be distributed to the public on a per capita basis. Ss for example if the carbon fee were $115 per ton of carbon, that’s equivalent to $1 per gallon of gasoline. With the amount of oil, gas and coal that we used in 2007, the collected tax would be $670 billion in the United States. If you distributed that to the legal residents, one share to each legal adult resident, that would be close to $3,000 per adult. And if you give half a share for children, up to two per family, then a family with two or more children would get $9,000 per year.

That would stimulate the economy and allow them to purchase the more efficient – next time they buy a vehicle, they buy a more efficient one and they insulate their home, whatever is necessary to reduce their carbon footprint. Because this fee on oil, gas and coal is going to increase energy prices. It’s going to increase the cost of gas at the pump and it’s going to increase your fuel bills for heating your home. But you’d like to minimize those, so that you get more in the dividend than you pay in your increased energy prices. Just looking at the distribution of incomes and energy use, about 60 percent of the people would get more in the dividend. The person who owns two houses and SUV’s and things would pay a lot more in increased energy than he gets in his dividend.

Q: What would prevent folks from paying their share on something that doesn’t contribute to the solution?

A: Nothing, except they would know this carbon price is going to continue to go up, and most people in the long run are going to start to adjust their habits. The fee is not enough. You should also have regulations. You should have vehicle efficiency regulations and lighting efficiency and building standards and things like that, because even at a dollar a gallon, many people have so much money they don’t care.

But what would happen, if you have this gradually increasing carbon price, you’re going to hit some points at which alternatives become cheaper, at which renewable energy or some energy-efficiency device becomes cheaper than the fossil fuel. And then those things are going to suddenly take off and you get amplifying feedbacks. And so eventually we would move toward the post-fossil-fuel era and get off this addiction to fossil fuel. But we’re never going to get off this addiction as long as it’s the cheapest form of energy.

Q: The book is entitled Storms of My Grandchildren: The Truth about the Coming Climate Catastrophe and Our Last Chance to Save Humanity. Why is it a catastrophe or will it be a catastrophe? Some scientists say, well, things are changing, but we can adapt.

Q: The book is entitled Storms of My Grandchildren: The Truth about the Coming Climate Catastrophe and Our Last Chance to Save Humanity. Why is it a catastrophe or will it be a catastrophe? Some scientists say, well, things are changing, but we can adapt.

A: The changes that have occurred so far, they’re moderate. You can see effects – the Southwest becoming drier and having more fires, same thing in the Mediterranean region and Australia, the places where the subtropics are beginning to encroach poleward. But the catastrophe is when we pass tipping points. And the single tipping point of greatest concern is the stability of the ice sheets. We see that Greenland is now losing mass at a rate of almost 300 cubic kilometers per year. Even more ominously, West Antarctica is losing mass at a rate of more than a hundred cubic kilometers per year. Those rates are higher than they were five years ago.

The primary mechanism is the fact that the ocean is absorbing more heat and it’s melting the ice shelves – the tongues of ice that stretch out from the ice sheets into the ocean. As those shelves melt, that allows the ice streams – the faster-moving part of the ice sheet – to discharge icebergs faster to the ocean. And that’s what we see happening in both of the major ice sheets. We know from the earth’s history that once ice sheets begin to disintegrate, they can disintegrate quite rapidly.

The transition from the last ice age to the current interglacial period, there was a time when sea level went up five meters per century for several consecutive centuries. That’s one meter every 20 years – because the Laurentide ice sheet went unstable. And once it starts to disintegrate, it sloshes into the ocean pretty rapidly. If that begins to happen, when Greenland starts putting out ice fast enough that the North Atlantic is cooled by the ice – and the same thing with West Antarctica – that’s why I talk about the storms.

Because that will keep the North Atlantic relatively cool – even a little cooler than it is now – but the low latitudes and the mid-latitude land areas will continue to be warmer as they have been for the last three decades. So the temperature gradients between the warm areas and the cool ocean areas will get larger. And it’s those temperature gradients that drive mid-latitutde cyclonic storms. So those storms are going to get stronger. And when you combine that with rising seal level, even when it reaches a meter-type sea level, it’s going to be disastrous for hundreds of cities around coastal areas – the kind of storm that the Netherlands and England experienced in the 1950s.

When you get storm surges of several meters of sea level combined with the rising sea level and the increasingly strong mid-latitude cyclonic storms, that’s going to be something that you don’t adapt to. And that will be a chaotic situation which will have economic and social chaos as a consequence. So you don’t want to pass that tipping point where ice sheets become unstable. But that’s what will happen this century if we stay on business as usual. And then with that kind of chaos in place, we will probably pass the tipping point where the methane hydrates, methane clathrates, the frozen methane in the tundra, and continetnal shelves begins to melt and release methane to the atmosphere. And we know that has happened during the earth’s history. The PETM event, Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum, got a sudden wwarming between 5 and 9 degrees Celsius when an amount of methane was released – the carbon equilvalent to all of the fossil fuels. So it’s something that can happen.

Q: So these tipping points lead to additional feedbacks?

A: Yeah, amplifying feedbacks.

Q: Is there a contradiction in this dire a warning on the one hand and on the other hand your willingness to forgo steps toward addressing the problem – Copenhagen, Congress?

A: Copenhagen doesnt address the problem, so what we need – the problem with the Kyoto-type approach, it takes a decade. Look at what happened after Kyoto. The emissions accelerated. The absolute amount of emissions and their percentage, their exponential rate of growth, all accelerated after the Kyoto agreement because – well, there were a few countries, actually, that reduced their emissions, but mostly that was via offsets and the fact that they exported their industry. So industry moved from [developed] countries to developing countries where it was cheaper, and products were then sent back to Europe.

You’re just displacing it. And that’s exactly what will happen as long as fossil fuels are the cheapest form of energy – their use is just going to increase. And there is no way to make that agreement universal. Russia, Saudi Arabia, many countries have no incentive to be part of that. And that’s why Russia was kind of bribed into nominally signing Kyoto, though it didn’t affect their emissions in any way. Their emissions actually fell because their economy collapsed.

Q: You feel that we still have a certain amount of time?

A: We have very little time and that’s why we need an approach that would work rapidly. And it has been demonstrated in British Columbia, which adopted two years ago a carbon tax with a 100 percent dividend, where they provided their dividend in the form of a payroll tax deduction. But that became the election issue in the next election. The opposition party raised that carbon tax as the main issue, and the incumbent party was voted back into office because the public could see their payroll tax had been reduced and they were happy to have a carbon price. So now the opposition party has adopted it as part of its platform also.

Five months after the law was passed, the whole system was in place and functioning smoothly because it’s so simple. A carbon price is so simple. You just place the fee at the mine or the point of entry. Cap and trade is a nightmare, which would take years if not decades to try to implement in contrast to a simple fee at the mine. So I’m not slowing down anything with that proposition. It’s actually speeding up the actions.

Q: What is your reaction – I’ve read a couple of comments you’ve made and wonder if you could share some of your thoughts with me, too, about the leaked emails at the University of East Anglia, which some critics of climate science and action to reduce greenhouse emissions are saying produce evidence of flawed and manipulated findings. For readers who aren’t immersed in the subject, first off, how does this British university’s work relate to the work that you do do at the Goddard Institute?

A: We do very similar, we do analogous analyses of global temperature change, which are based on measurements made at several thousand weather stations around the world, on the continents and islands, and ocean measurements made by ships and satellites, and polar measurements made by research stations. All of that data is available on our website and the program that is used to do the analysis is available on our website. If any answer different from what we get for global temperature could be obtained, don’t you think the contrarians, the deniers, would leap on it? So it’s just nonsense with regard to the claim that the data, the conclusions, the global warming curves, can be manipulated.

Now that being said, the things that were being said – the discussions that were revealed in those emails – do show some problems. For example, East Anglia did not want to release the raw data that they were using. That is not a smart idea. The way science works, you have to release the data that youre using to get your conclusions so other people can check it. As I said, the data we use is released. It’s available on our website. It’s publicly available data. But now East Anglia realizes that – the tremendous public reaction – that they’re going to release their data also.

Another thing, they tried to stop contrarians from publishing in journals and when a journal published a contrarian paper, they said they’re going to boycott that journal from then on. I think that’s a bad idea. Eventually, any paper can be published. You send it enough places. So you have to rely – there are going to be some papers in the journals and you try to have good reviews and try to minimize the bad science being published, but eventually you’re going to have to rely on the review process by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and by the National Academy of Sciences.

In Al Gore’s movie, he talked about there were 930 papers that said global warming is real and there were zero that disputed that thing. Well, that doesn’t sound right. There are always going to be some people that disagree. That’s the nature of science, to be skeptical and to challenge and to publish a contrary piece.

So there were some things in those emails that were very unfortunate and they’re being very effectively used by the contrarians, by the people who want to continue business as usual. It’s a propaganda war, and they’re doing very well in the propaganda war, but they can’t do beans in the science war. As I said, the data is available. If they can produce a curve that looks any different than what we get for global temperature, they would do it in a heartbeat. But they can’t, because they can’t change the data.

Q: So there’s nothing in any of this email trove that’s been discovered and put online that in your view in any way undermines the broad message from the scientific community?

A: Not the broad message. There are arguments about things like how strong was the Medieval warming and the tree ring analyses. There are details. But it does not undermine the science that humans are now in control of global climate. We have become by far the strongest forcing of climate. And the climate that our children and grandchildren are going to experience is determined by the changes in atmospheric composition that humans are making.

Q: You’ve been, I think it’s fair to say, tremendously influential in conveying scientific findings about global warming since the late ’80s and you’ve taken on an increasingly visible role as a political activist as well. For a time in recent years, it seemed that U.S. public opinion was moving in your direction on this issue, but this year in particular several polls have shown some slippage in public agreement, for instance, that global warming is even happening. Any thoughts on why that is? Is this disappointing? I guess it’s disappointing to you.

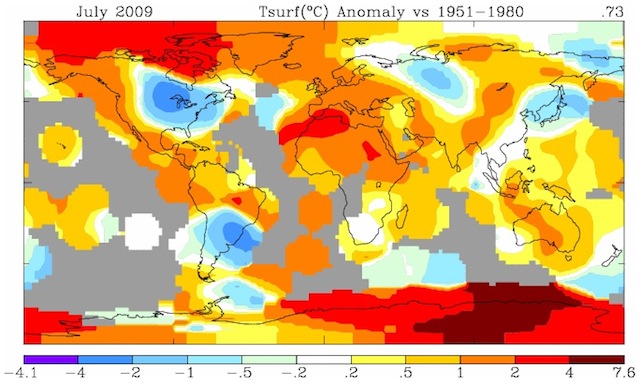

A: One of the biggest reasons is, if you look at a map of the global temperature anomalies this past year, especially last summer, there’s a big blue region in our maps. It’s centered in mid-America. People continue to confuse weather and climate. We had a very cool summer in 2009. Summer – June, July, August – averaged over the world was the second warmest summer in the 130 years of instrumental data, but it was one of the coolest summers in the United States.

July 2009 temperatures vs. 1951-80 temperatures, NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies

The United States – the 48 states – cover one and a half percent of the world. But our view of global warming – the person in the street is looking at what the weather is like where he’s living. That was one of the points I tried to make in the 1980s with my colored dice. And I showed that by the time you got to the first decade of this century, instead of having two red, two white and two blue sides for this die, it became four red, one white and one blue. One blue is the cold – colder than normal – which normal was the 1950 to 1980 climatology. So you still got one chance in six of rolling a season that’s going to be cooler than normal and that’s what happend in 2009. I have five sisters living in the Midwest and some of them are pretty conservative. It convinced some of them – aw, global warming must be wrong.

Q: Even your own sisters? Well I guess it illustrates what a tough job it is to try to get your science out to the public at large.

A: That is right. That’s part of the problem.

Q: What about next year? What do you think?

A: Next year is going to be very warm. It could be the warmest year in the instrumental record. You know, 2008 was the coolest year in this century, in the first decade of this century, because it was a very strong La Niña. There’s this natural oscillation of tropical equatorial ocean temperatures in the Pacific Ocean due to the way the dynamics of the ocean works. It was in a cool phase in 2008 and now it’s moved, in the last few months, into an El Niño phase. How storng that El Niño is going to be is still unclear. It’s moderate strength now.

If it continues to strengthen, then 2010 is almost surely going to be the warmest year in the record, even though the solar irradiance is now in a strong solar minimum. It goes through these 11-year cycles and it’s at its lowest point now. And in fact it’s at the weakest minimum since we started making measurements in the 1970s. The sun is now coolest. And that’s what caused many solar scientists to think the sun controls everything and that’s why last year was cool. But it was cool last year becase of the La Niña. The sun does contribute but the forcing due to increasing CO2 in seven years is enough to cancel the effect of the sun staying down. So even if the sun stays down in the longer minimum of a few centuries ago, that effect is offset by seven years’ growth in CO2.

So the truth is, humans are now in control of climate. There are natural factors like the sun, which varies, and El Niños and La Niñas, which cause year-to-year changes, but the long-term trend is now completely under the control of humans. Even the person on the street is going to admit that in a decade or so, but we don’t have a lot of time for the policy actions to begin to take place. That’s what is the concern. And that’s why we need to put a price on carbon emissions. That’s the only way we are going to reduce our addiction to fossil fuels. Right now we have places that are starting to squeeze oil out of coal, starting to squeeze oil out of tar sands, even the possibility of squeezing it out of the oil shale in the Rocky Mountains. That we can’t do without do without destroying the future for young people.

Q: Has your political activism and your increasing outspokenness in recent years on policy and political questions undercut in any way your credibility as a scientist? Some of your critics have tried to make that case.

A: Well, I don’t think so because science has its own ways of judging the merits of scientific papers. It’s done by the peer review process and publication. I prefer to do science. I just realized the policymakers were continuing to ignore the implications of the science. They say words as if they understand the issue. They talk about a planet in peril and such things. But what I realized was that their words are basically greenwash. They learn to say the right words because some of the public feels it’s important to deal with environmental issues, but they’re not willing to take the actions which will upset business as usual and the fossil fuel interests in particular.

You see what tremendous clout the coal industry has, for example, even though it’s a $50-billion industry. Compare that to the trillion dollars we spent on bailing out the banks and trying to solve the econmic crisis. But even though it’s a small industry it has so much influence on our politicians, including the president.

[Disclosure: The Cynthia & George Mitchell Foundation was a sponsor of James Hansen’s talk to The Progressive Forum. Businessman George Mitchell founded the Houston Advanced Research Center, publisher of Texas Climate News.]