By Bill Dawson

Texas has not kept pace with many other states in adopting policies that address global warming – a distinction that the Legislature left unchanged in its 2009 session.

Some Texas government and business leaders, meanwhile, have been outspoken in opposing federal regulations to combat climate change, particularly the American Clean Energy and Security (or ACES) Act, which barely won House approval in June.

Some Texas government and business leaders, meanwhile, have been outspoken in opposing federal regulations to combat climate change, particularly the American Clean Energy and Security (or ACES) Act, which barely won House approval in June.

Still, the recently conducted 2009 editions of a pair of annual polls – the Texas Lyceum Poll and the Houston Area Survey – suggest that Texans’ opinions on various aspects of the climate issue are not very different from those of Americans in general, including support for stepped-up regulatory action.

One point of similarity relates to the proposed national cap-and-trade system for reducing emissions of greenhouse gases produced during the use of oil, coal and other fossil fuels. The ACES Act – also known as the Waxman-Markey bill after its House sponsors – would impose a gradually lowering limit on greenhouse emissions and create a system of tradeable emission permits.

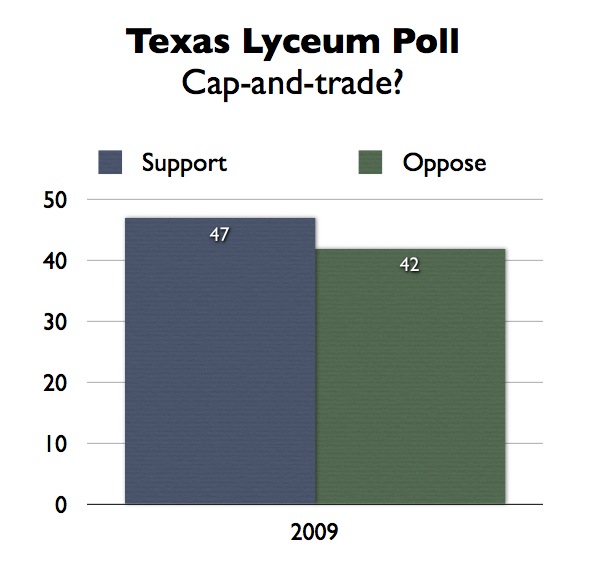

The Texas Lyceum Poll surveyed 860 adults statewide from June 5-12 on a variety of economic and other issues. It was the third annual poll by the Texas Lyceum, a nonprofit, nonpartisan leadership organization.

One question directly addressed the cap-and-trade concept:

There’s a proposed system called “cap and trade.” The government would issue permits limiting the amount of greenhouse gases companies can put out. Companies that did not use all their permits could sell them to other companies. Supporters argue that many companies would find ways to put out less greenhouse gases, because that would be cheaper than buying permits. Opponents argue that this amounts to a huge tax on large companies. Would you support or oppose this system?

Forty-seven percent of the respondents said they supported cap-and-trade. Forty-two percent were opposed. The rest – 11 percent – didn’t know or wouldn’t say.

In a national poll of 1,001 adults, conducted June 18-21 for the Washington Post and ABC News, an almost identically worded question was asked, but without the sentence about opponents’ “huge tax” argument. The surveyfound a slightly larger national margin of support for cap-and-trade than in the Texas poll – 52 percent in favor and 42 percent opposed – with 6 percent having no opinion.

To test how strong that support was, the Post-ABC pollsters also assigned hypothetical personal costs to a cap-and-trade proposal in a pair of followup questions.

For a plan that would “significantly” lower greenhouse gases and raise the respondent’s electricity bill by $10 per month, 56 percent said they were in favor and 42 percent were opposed. However, when the monthly addition to the household power bill was pushed to $25, the numbers turned around – only 44 percent in support and 54 percent opposed. (The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated on June 19 that the ACES bill would cost the average household about $14 per month in 2020, but added that this did not include “the economic benefits and other benefits of the reduction in GHG emissions and the associated slowing of climate change.”)

Both the Texas Lyceum and the Post-ABC polls were conducted as debate over the ACES bill, and especially its potential costs, was heating up in the immediate prelude to the 219-212 House passage of the measure on June 26. The Texas delegation split largely along party lines, with Republicans voting 20-0 against the bill and Democrats voting 9-3 in favor.

The 2009 Houston Area Survey, conducted for more than a quarter-century under the direction of Rice University sociologist Stephen Klineberg, comprised questions on a variety of issues that were posed to 706 Harris County residents by the University of Houston’s Center for Public Policy from Feb. 3-25.

The 2009 Houston Area Survey, conducted for more than a quarter-century under the direction of Rice University sociologist Stephen Klineberg, comprised questions on a variety of issues that were posed to 706 Harris County residents by the University of Houston’s Center for Public Policy from Feb. 3-25.

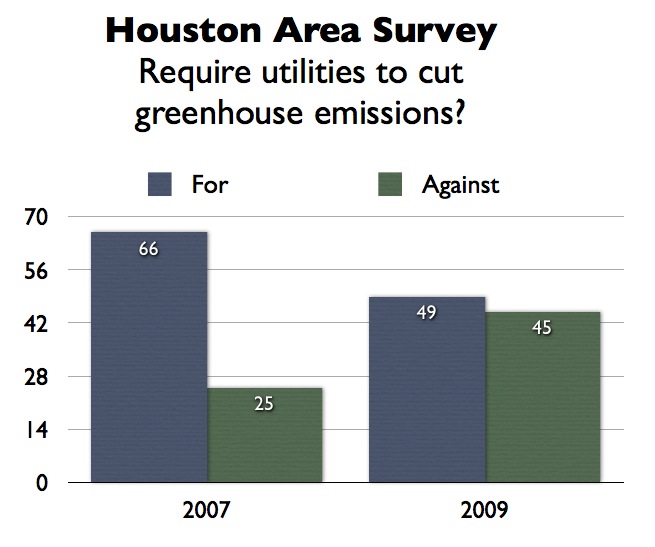

One notable change in the survey findings was recorded when respondents were asked a question that had been included in the 2007 edition of the poll: “What about requiring utilities to reduce their emissions of greenhouse gases, even if this means that electricity rates will rise?” (Unlike the Post-ABC poll, the Houston Area Survey did not pin a specific dollar figure to the emission reduction.)

In 2007, a large majority had said they were in favor of a mandate to utilities to cut greenhouse gases, with 66 percent for the idea and only 25 percent opposed.

By the time of the 2009 survey, however, support for the idea had plummeted. This year, 49 percent favored an emission-cutting requirement for electricity producers and 45 percent were against it – similar to the 47-42 margin in the statewide Texas Lyceum Poll for the cap-and-trade idea, which would not just affect the utility industry.

The 2007-2009 change that was recorded in the Houston Area Survey on the question of a utility-targeting requirement, coming as it did soon after “a serious economic recession” gripped the United States last year, was “highly significant,” Klineberg told Texas Climate News.

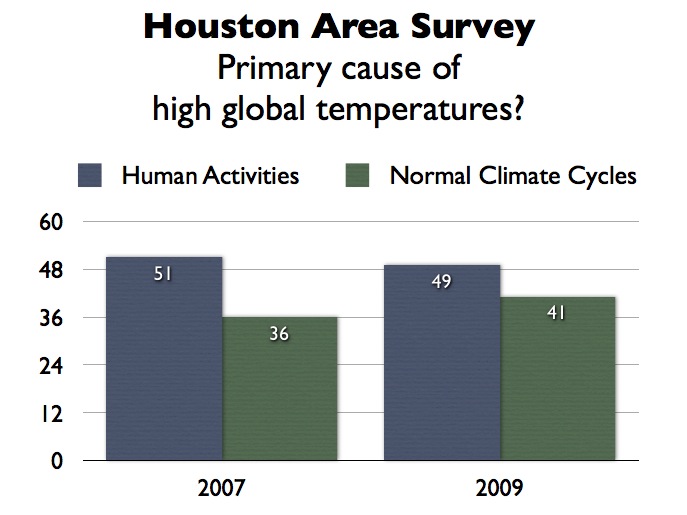

One thing that essentially did not change from 2007 to 2009 in the Houston Area Survey, however, was the belief by people in the oil capital that human activities, not natural variability, is the main driver behind global warming.

Both years, pollsters asked this question: “What do you believe is the primary cause of the high global temperatures we’ve experienced in recent years? Are they mainly caused by human activities, or are they mainly caused by normal climate cycles?”

Both years, pollsters asked this question: “What do you believe is the primary cause of the high global temperatures we’ve experienced in recent years? Are they mainly caused by human activities, or are they mainly caused by normal climate cycles?”

In 2007, 51 percent of respondents said the main cause was human activities and 36 percent said normal cycles. In 2009, 49 percent said human activities and 41 percent said normal cycles. Given the poll’s margin of error, Klineberg said the 2009 finding represented no significant change.

A striking feature of the Houston Area Survey findings on questions about climate in recent years is “the degree to which it has become a partisan issue,” Klineberg said.

He discovered a growing separation in the views of Democrats and Republicans on environmental issues in general between 1990 (when there was essentially no partisan difference) and 2000, a period when he conducted the statewide Texas Environmental Survey.

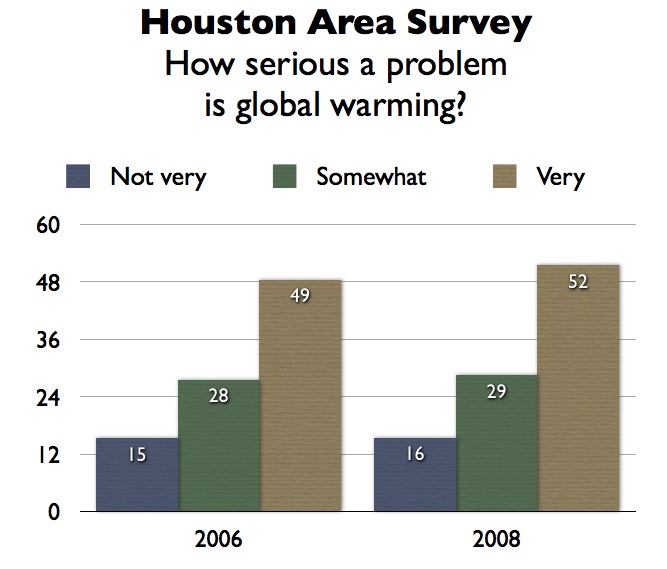

The party divide was evident last year in a Houston Area Survey question that was not asked in 2009: “How serious a problem would you say is the ‘greenhouse effect,’ or the threat of global warming? Would you say: very serious, somewhat serious, or not very serious?”

In 2006 and 2008, both years when that question was posed, large majorities (77 percent in 2006 and 80 percent in 2008) answered “somewhat” or “very” serious. A major difference was manifest between the responses of self-identified Republicans and Democrats – in 2008, for instance, 32 percent of Republicans and seven percent of Democrats said “not very serious”, while 30 percent of Republicans and 68 percent of Democrats said “very serious.”

Likewise, on the question about the main cause of global warming – human activities or normal cycles – a large partisan divide was evident. In 2009, 69 percent of Democrats and 36 percent of Republicans said human activities, while 64 percent of Republicans and 31 percent of Democrats said normal cycles.

Likewise, on the question about the main cause of global warming – human activities or normal cycles – a large partisan divide was evident. In 2009, 69 percent of Democrats and 36 percent of Republicans said human activities, while 64 percent of Republicans and 31 percent of Democrats said normal cycles.

A growing partisan split on questions about climate change has been evident in national polls, as well.

The Gallup Poll, for instance, has been asking Americans since 1998 whether they think that mainstream news reporting generally exaggerates, is generally correct about, or generally underestimates the seriousness of global warming.

In 1998, 35 percent of Republicans and 23 percent of Democrats thought it was exaggerated. This year, however, in a survey of 1,012 adults in March, the party split of 12 percentage points had grown to a 44-point division, with 66 percent of Republicans and 22 percent of Democrats saying that news accounts generally exaggerate the seriousness of global warming.

A national opinion survey of 3,006 adults by the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press and the American Academy for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) between April and June also found what the pollsters called a “stark partisan divide” on climate change. On the question of causation of global warming, the report included this observation:

The strongest correlate of opinion on climate change is partisan affiliation. Two-thirds of Republicans (67 percent) say either that the earth is getting warmer mostly because of natural changes in the atmosphere (43 percent) or that there is no solid evidence the earth is getting warmer (24 percent). By contrast, most Democrats (64 percent) say the earth is getting warmer mostly because of human activity. Nearly half of independents (49 percent) say human activity is causing the earth to warm, while 47 percent say either that the earth is getting warmer due to natural atmospheric changes (38 percent) or that there is no solid evidence that the earth is warming (nine percent).

The divide is even larger when party and ideology are both taken into consideration. Just 21 percent of conservative Republicans say the earth is warming due to human activity, compared with nearly three-quarters (74 percent) of liberal Democrats.

In a survey of 2,553 scientists for the same Pew-AAAS report, 84 percent said the earth is warming because of human activity.

Reflecting on these and other national opinion surveys in recent months, Klineberg said environmentalists may find it easy to think the nation has “turned a corner” on the climate issue.

“But the polls indicate it is still a tough sell,” he added. “By no means is this battle over.”