For more than two decades now, scientific warnings have been accumulating about the risks posed to the Texas coast by rising sea levels that scientists say are being propelled by manmade climate change.

For more than two decades now, scientific warnings have been accumulating about the risks posed to the Texas coast by rising sea levels that scientists say are being propelled by manmade climate change.

Another such alert was sounded in a lengthy federal study released this month by the Environmental Protection Agency, U. S. Geological Survey and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. One of numerous research projects commissioned by the U.S. Climate Change Science Program, the report focused on sea-level hazards confronting the mid-Atlantic region as a case study. It also included considerable general discussion relevant to other coastal areas.

John Anderson

Regarding Texas, the report said: “The mid-Atlantic region is highly vulnerable to sea-level rise, but regions like the central Gulf Coast (Louisiana, Texas) are just as vulnerable or more so.”

Another passage, while not geographically specific, may strike a chord with Texans mindful of the state’s direct and indirect experiences with hurricanes Ike, Rita and Katrina:

Rising sea level increases the vulnerability of development on coastal floodplains. Higher sea level provides an elevated base for storm surges to build upon and diminishes the rate at which low-lying areas drain, thereby increasing the risk of flooding from rainstorms. Increases in shore erosion also contribute to greater flood damages by removing protective dunes, beaches, and wetlands and by leaving some properties closer to the water’s edge.

Another passage is typical of the study’s general conclusions pertinent to Texas, given the state’s history:

At the current rate of sea-level rise, coastal residents and businesses have been responding by rebuilding at the same location, relocating, holding back the sea by coastal engineering, or some combination of these approaches. With a substantial acceleration of sea-level rise, traditional coastal engineering may not be economically or environmentally sustainable in some areas.

Last October, a Rice University faculty member warned of the combined impacts in Texas, Louisiana and Alabama of rising seas and dammed rivers in coming decades.

John Anderson, a professor of oceanography and Earth science, presented research findings to a geology conference that the university said represented “the most comprehensive geological review every undertaken of the upper U.S. Gulf Coast.”

In terms of sea-level increases and river sediments flowing into the bays, we’re rapidly approaching a time when bays will face conditions they last saw in the Holocene, from about 9,600 until 7,000 years ago. That period was marked by dramatic and rapid flooding events in each of these bays – events that saw some bays increase their size by as much as one-third over a period of 100 or 200 years. A Rice announcement quoted Anderson about the study, which included Galveston, Matagorda and Corpus Christi bays in Texas and Sabine Lake on the Texas-Louisiana border:

Anderson was further quoted: “There is no question that sea levels are rising in this region at a rate today that approaches what we saw in the Holocene.”

He noted that several recent studies have confirmed a doubling of the rate of sea-level rise along the Gulf Coast over the past century, while dam construction has greatly reduced river-borne sediment reaching bays.

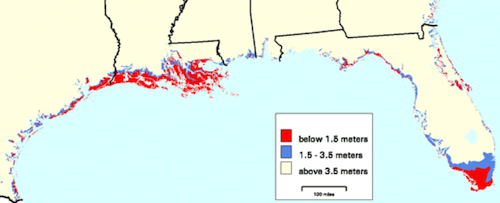

A federal study published in 2000 sought to refine scientists’ map-based understanding of where the largest risks of rising seas will be along the United States’ Atlantic and Gulf Coasts.

Those researchers concluded that about 58,000 square kilometers of land are lower than 1.5 meters in those regions, with more than 80 percent of these especially vulnerable areas in four states – Louisiana, Florida, North Carolina and Texas.

Texas had the fourth-ranking total area below 1.5 meters – about 5,177 square kilometers. Another 4,213 square kilometers in the state were found to lie between 1.5 meters and 3.5 meters.

Based on conclusions of the United Nations-sponsored Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2007 and projections in other recent studies, the federal report issued this month said that “global sea-level rise associated with climate change” is likely to range from 19 centimeters to one meter over the next century and possibly as much as four to six meters over “the next several centuries.”

Based on conclusions of the United Nations-sponsored Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2007 and projections in other recent studies, the federal report issued this month said that “global sea-level rise associated with climate change” is likely to range from 19 centimeters to one meter over the next century and possibly as much as four to six meters over “the next several centuries.”

The potentially serious ramifications of higher seas for Texas are nothing new for Jim Titus, the EPA’s project manager for sea-level rise, who was the lead author of the three-agency federal report published this month and a co-author of the 2000 study.

In 1988, the Houston Chronicle quoted Titus in an article examining the Texas risks of sea-level rise, accelerated by global warming, for people, coastal development and valuable ecosystems such as wetlands. In the story, he concurred with a researcher who had studied the threats to the Galveston Bay area:

“It’s hard to envision a lot of benefits for Texas” from higher oceans caused by the (human-fueled) Greenhouse Effect, agreed Jim Titus, the EPA’s project manager for sea level rise.

Projects to prevent or mitigate some effects of rising seas “are all going to cost money,” Titus said. “People will have to ask, would we rather avoid global warming than have all these costs.”

– Bill Dawson

Disclosure: Texas Climate News editor Bill Dawson also teaches as a part-time lecturer at Rice University.