Installing solar panels on the roof of a home in San Antonio

By Greg Harman

When CPS Energy, San Antonio’s publicly-owned utility, mailed out letters to the owners of solar-sporting homes in early April announcing that it was considering a program that would cut payments for sun-derived energy nearly in half – from 9.7 cents per kilowatt hour to roughly 5.6 cents – residents were shocked. CPS, the state’s most aggressive utility in pursuing centralized solar systems – currently on track for 440 megawatts from so-called “utility-scale” solar projects – appeared to be backpedaling fast on the decentralized rooftop variety.

Although the city’s solar installers weren’t included on that initial mailing, they heard about the proposed SunCredit system soon enough. As Lanny Sinkin, director of the non-profit advocacy group Solar San Antonio, remembers it, cell phones erupted at an April 9 gathering of solar representatives and utility officials as frantic customers sought answers. “All their cell phones are lighting up,” Sinkin said. “[CPS] really did convince the solar installers they were trying to kill the industry.”

Tony Contreras, head of business development for CAM Solar, which moved its headquarters to San Antonio from Frisco, near Dallas, in 2011, fielded one of those calls. “First of all, it was confusing to them,” Contreras said. “It was worry and concern that something had changed related to their investment in solar. That it was now going to be different than they had committed to.”

The proposal potentially threatened to double the amount of time it would take for a home solar system to pay itself off, from seven or eight years to 16 years or more, Contreras said.

Responding to strong customer and solar-industry resistance, CPS began tweaking the proposal. It suggested, for instance, that new solar customers who completed registration forms by May 31 would be grandfathered into the net metering program at the rate of 9.7 cents. The program tracks and provides credit for surplus electricity that a solar home feeds back into San Antonio’s power grid.

While some installers told Texas Climate News they saw a jump in business from homeowners eager to beat a policy shift, Contreras blamed the uncertainty injected into the market for more than an estimated $100,000 in lost or delayed revenue.

Sinkin said his staff logged a total of 74 projects valued at $17.7 million that were either cancelled or put on hold due to the announcement. “I don’t know who thought up introducing SunCredit the way they did, but they could not have done it in a worse way. It just upset everybody and turned everything upside down.”

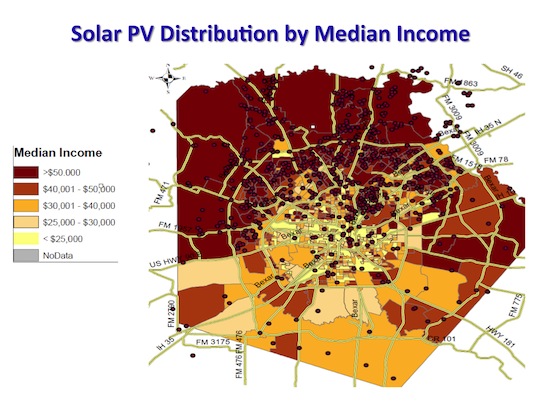

The flare-up was tamped down at a private May 8 meeting between Sinkin and CPS CEO Doyle Beneby following a single public hearing on May 3. But the root of CPS Energy’s objection to net metering remains. It’s an argument that has grown commonplace in the electric-service industry, which alleges in various locations across the country that a widening “solar divide” unfairly burdens low-income homeowners with an increasing share of the cost of maintaining utility operations as more and more upper-income homeowners seek personal energy independence with rooftop solar.

Beneby agreed to allow San Antonio’s current net metering program to remain in effect for another year as the two sides studied the utility’s concerns at a series of meetings between representatives of the solar community, CPS employees, and “other stakeholders,” according to a CPS press release.

The shakeup represents the second time CPS has sought to significantly change the rules governing the solar program it launched three years earlier. The first one came in 2012 when, after committing $40 million to solar rebates under an ambitious plan to reduce energy consumption by 771 megawatts by 2020, CPS officials proposed reducing the amount available to the solar program from the $6.2 million spent in 2011 to $3.9 million, while cutting the rebate from $2.50 per installed watt to a flat $2.

Lanny Sinkin, director of the advocacy group Solar San Antonio, is flanked by San Antonio Mayor Julián Castro (left) and former Mayor Henry Cisneros at the 100th birthday party held in May for Sinkin’s father, Bill Sinkin, the founder and chairman of Solar San Antonio and a longtime community activist in the city

Mayor Julián Castro, who less than a year earlier had pledged to make San Antonio the center of the clean-tech universe, went to bat for solar, making sure that solar rebates remained in step with the growth of the industry. The utility spent an estimated $10 million on solar rebates in 2012, according to Sinkin, and has now spent roughly half of that $40 million set aside years earlier.

This time, however, the argument isn’t about adjusting to the runaway success of the solar industry. This time the utility has hung its argument for reducing solar reimbursements on the more difficult issue of economic justice.

“Costs to install photovoltaic systems continue to fall, making them increasingly available for more customers. And with that growth, the costs of the utility infrastructure are borne by fewer customers — those who don’t have solar systems,” Cris Eugster, executive vice president and chief strategy and technology officer for CPS, was quoted as saying in an April 9 press release. “To ensure that solar customers continue to enjoy the benefits of any distributed energy they produce, and pay a fair share of the infrastructure that they rely on, we’re taking a different approach. This is really important in San Antonio, where one quarter of the community’s residents are at or below the poverty level, and monthly energy bills absorb a larger portion of their monthly budgets.”

Since arriving in San Antonio in 2010, Beneby has repeatedly raised the issue of economic fairness in energy matters at the quarterly gatherings he initiated with members of the local environmental community, according to Peggy Day, chair of the Sierra Club’s San Antonio chapter. “In the end it’s the poor people who end up paying for all the infrastructure costs because the wealthy people have been able to disengage themselves from all of the services that are centralized by having their own LEED-certified houses with solar and getting off the grid – that kind of thing,” Day said, recounting Beneby’s reasoning. “It is definitely a Beneby concern. He’s broached that issue before. We’ve been meeting with him a couple years now and it’s come up a couple times now and it’s Beneby that brings it up.”

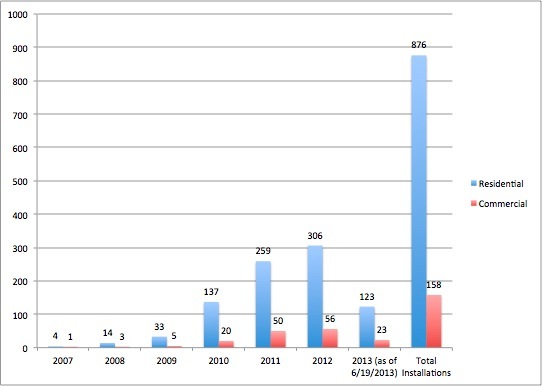

The pace of residential rooftop solar installations jumped in San Antonio after CPS Energy’s rebates were introduced in 2010, especially in upper-income zip codes along the north and northwest fringes of its service area. In 2007, only four residential systems were installed in CPS’s service territory. In 2009, there were 33 new installations. But the number grew to 137 in 2010 and 259 in 2011. Last year, 306 rooftop installations went in across greater San Antonio, according to data assembled by Solar San Antonio. That brought the overall number of residential solar arrays to 876. Another 158 private commercial systems are in place. But the total is still a statistical blip in a system with more than 728,000 electric customers.

While Beneby did not respond to repeated requests for an interview, Eugster told Texas Climate News that rooftop solar unfairly burdens lower-income customers with the fixed costs of heavily financed power plants, transmission lines and the like. “It is a complex issue and there are a lot of nuances. How do you make this fair to all ratepayers and at the same time support the local industry and support the local rooftop solar industry – that’s the challenge we’re trying to address.”

It is not a novel argument among utilities or solar advocates dedicated to bringing pricey solar systems into low-income communities around the country.

Sinkin dismisses the utility’s concern, saying that there is still far too little rooftop solar to have any impact on anyone’s bill. He said the environmental-justice talking point was designed to get a political foothold in a city still strongly divided along race and class lines. “It was politically useful at the time,” he said. “When you talk to a city council where many represent low-income [communities], you’re going to argue that solar hurts low-income.”

Justice and jobs

Veteran California activist Bill Gallegos blames the lack of solar panels atop inner-city homes on the fact that much of the renewable energy legislation in the country has been made in consultation with what he calls the “big green groups” – organizations with political clout that haven’t traditionally been driven by economic-justice concerns and whose members tend to be both affluent and Anglo. The executive director of Communities for a Better Environment in South Los Angeles has been OK with the rooftop solar divide. Mostly. Because of the seriousness of the threat posed by climate change, expected to hurt the global poor far more than those with resources to adapt in the short term, the faster utilities get off fossil fuels the better, he said.

“On the other hand, we feel like, who got the worst of the fossil fuel infrastructure? It’s low-income communities of color. We get it all,” Gallegos said. “We get the freeways, we get the diesel trucks, we get the rail yards, we get the ports, the power plants, the oil refineries.”

For that reason, Gallegos and others fighting to interject environmental-justice considerations into the rollout of renewable technologies around the country hope to begin making up for patterns of discrimination that followed the industrial and chemical revolutions, resulting in swaths of endemic poverty, reduced opportunity, and, in many cases, public-health problems. As Uma Outka, a law professor at the University of Kansas, points out in a 2012 paper on the subject, decentralized renewable energy may not only avoid the harms of older energy technologies, but also deliver cost savings and economic development to traditionally neglected communities.

“High upfront costs for rooftop solar have limited access for low-income households, despite their greater need for the long-term savings that solar energy systems can provide,” Outka writes. “With new financing models, incentives, and targeted initiatives, access to onsite renewable energy in low-income communities is slowly increasing in the United States and around the world.”

While few states or communities are legislating renewable development with the low-income in mind, it is happening.

A “Solar For All” bill requiring that a small percentage of California’s decentralized solar power be constructed in low-income areas – a “foot in the door,” according to Gallegos, who helped champion it – failed at the California State Assembly last year with utility resistance. However, new bills this session – promoting community solar projects that would enable renters to band together for small-scale solar systems of less than 20 megawatts and aggressive commitments tying renewables to job growth in that state – are tilting the game.

California is committed to achieving 33 percent renewable energy by 2020, and a large chunk of this – 12,000 megawatts, by a governor’s executive order – must be from small-scale decentralized power systems. “In our view, the best way for that to happen is through small local projects that can be built in poor urban and rural communities,” Gallegos said.

Despite a “dismal” track record on solar, according to a recent report by the Los Angeles Business Council in partnership with UCLA’s Luskin Center for Innovation and others, the Los Angeles City Council and the city-owned Los Angeles Department of Water and Power approved a Feed-In Tariff program this year for decentralized solar and agreed to purchase up to 150 megawatts of surplus energy from local businesses and multi-family buildings, resulting in an estimated 4,500 jobs. By aligning rooftop energy production potential and jobs creation, low-income areas in downtown L.A. and the San Fernando Valley stand to gain under the effort, the Luskin report notes.

By way of comparison, CPS Energy’s deal with OCI Solar for a 400-megawatt centralized solar system and solar manufacturing plant is expected to provide about 800 “long-term” jobs, according to the utility.

If L.A.’s target were raised to 600 megawatts, LABC President Mary Leslie wrote in an April 30 opinion column in the Los Angeles Business Journal, the number of jobs created could leap to 16,000.

Asthma City

On the roof of Anya Schoolman’s three-story townhome in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood of Washington, D.C., dozens of field-tripping schoolchildren are ogling her solar array. From here another three arrays are visible on roof after roof, out to the horizon. More can be seen out the back. Invisible is the string of aged coal-fired power plants that ring the District, supplying much of its power. She always asks the troops of local public-school students who visit her home the inevitable question: “How many of you have asthma?” Easily half the hands go up.

When it comes to solar power, Schoolman says, public interest comes preloaded. “We never have to convince people why, you have to tell them how. It cuts across class, it cuts across race, it cuts across income. If anything, we get it stronger from the low-income neighborhoods because they actually have much more serious health problems.”

Washington, D.C., ranks highest in the nation for childhood poverty. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, the metro area also has the highest rates of asthma. In 2008, 12.6 percent of children had asthma, compared to 9 percent in most of the rest of the nation. The percentage of Washington children expected to get asthma at some point in their lives stood at 18.4 percent, compared to roughly 13.3 percent within the 38 states participating in the CDC’s National Health Interview Survey. Further, in 2011 the CDC estimated that 40 percent of the uninsured families in D.C. could not afford their prescription medicines.

Founder of two organizations dedicated to bringing emission-free sun power to those least likely to be able to plunk down $30,000 for a new rooftop array, Schoolman says solar discrimination is an issue people need to contend with. “It actually is a real issue that environmental activists need to be aware of. Renewables do cost something. You can’t just pretend they don’t,” she said. “Therefore, what we need to do as environmental groups is really fight to make sure the incentives are distributed in a really fair way.”

D.C. residents already feel victimized by their utility, Potomac Electric Power Company, or Pepco, named the “most hated company in America” by Business Insider in 2011, she continued, speaking of a “visceral hatred” that makes ratepayers want to “free themselves.” While the electric rates are on par with the national average, Pepco customers suffered from 70 percent more power outages, Business Insider reported, and, according to analysis by the Washington Post, the lights tend to stay out twice as long. A regulatory provision further allows the utility to charge residents a fee for periods they do not receive power. Finally, there are the coal plants around D.C., which the non-profit Clean Air Task Force estimates are responsible for an estimated 299 deaths each year in the greater D.C. area, as well as 259 hospital admissions and 480 heart attacks. (The organization draws on epidemiological studies by a team of Harvard researchers who use computer modeling to compare power-plant-linked particulate levels at ground level with U.S. Census data and the known health risks of fine particulates.)

When Schoolman, founder of the Mount Pleasant Cooperative, began to lobby the District in 2008 to expand solar initiatives in low-income neighborhoods across D.C., the reaction from city officials was sharp. “We were literally hearing from the government, ‘Solar is for rich white people and energy efficiency is for low-income black people,’ and we were like, ‘Have you asked them how they feel about that?’” (Efforts to contact officials with the District’s Department of Environment were unsuccessful.)

Over time, the conversation changed. While the Mount Pleasant co-op now boasts 50 installations, about a dozen more co-ops under the umbrella of D.C. Solar United Neighborhoods have since taken root and count hundreds of arrays, generally around 4 kilowatts in size, across several city wards.

Since launching a Sustainable Energy Utility to oversee monies collected through the privately held electric provider Pepco in 2008, the D.C. Department of the Environment has specifically earmarked funds for low-income residents. By increasing rebates for low-income residents to $3 per watt, as San Francisco has done, and partnering homeowners with a third party responsible for ownership and maintenance of the rooftop solar systems, residents with credit problems and limited income can still benefit from a solar array on their roofs.

Yet it’s slow going.

By the end of 2012, the District had partnered with 18,795 residents on energy efficiency or renewable energy projects, reducing peak electricity demand on power plants by 3,732 kilowatts. And yet low-income participation in the solar power program remains low, according to the District’s Sustainable Energy Utility’s annual report in 2012.

“For many District residents, however, the initial cost barriers are too high, and participation rates for low-income residents are low,” the SEU’s report says. “This observation is borne out by data showing very few renewable energy installations east of the Anacostia River, where there are greater concentrations of low-income households.”

Driven by a concern about global warming, Pat Bailery in the Shepherd Park neighborhood was one of the first to tap into the District’s grant program back in 2009. “It happens to be the most generous grant in the U.S. – if the funding is available,” she said.

While the terms have improved since she installed her rooftop system, receiving about $1,600 per kilowatt from the District at the time, residents were wary when she first approached them. “People were tremendously turned off by the up-front cost of the solar panels,” Bailery said. “It wasn’t well received.”

Long wait times and the complex structures of the various local and federal rebate programs make it difficult, she said. “I wish it could be easy. People can’t understand. A grant, renewable energy credits, feeding into the grid – it’s complicated.”

Planting solar gardens

About the same time Bailery was watching her 4.2-kilowatt system being bolted to her sloped slate roof, and as CPS Energy was rolling out its solar program for the first time in San Antonio, Joy Hughes was helping work out some of the fine points of a decidedly simpler solar model, one she and many others in the solar community say will help bring solar into areas that have historically been excluded. Hughes, founder of Colorado-based Solar Gardens Institute and CEO of Solar Panel Hosting LLC, calls today’s solar divide “a real issue” and “a vulnerability for solar supporters.” However, she adds, it would be wrong to say, “’Oh, it’s not equal, so we’ll take away solar for everybody.’”

Workers for a solar power company based in Boulder, Colo., install rooftop panels

The way to respond, Hughes argues, is through legislation like the Solar Gardens Act, passed by the Colorado General Assembly in 2010, five years after the Centennial State passed a renewable energy standard mandating that utilities purchase 30 percent of their power from renewable sources by 2030. The Solar Gardens law provides a way for renters, low-income communities, rural agricultural producers, and those whose homes aren’t positioned in a way to benefit from a rooftop array to tap into solar by buying shares in small-scale, off-site arrays – “solar gardens.” Though preceded by similar measures in Maine, Vermont, Washington State, and Massachusetts, Colorado’s solar gardens law is unique in that it instructs the state’s Public Utilities Commission to ensure that 5 percent of the power produced by solar gardens goes to low-income communities, Hughes said.

While utilities in California blocked a similar bill last year, Xcel Energy supported Colorado’s Solar Gardens Act. “It gives these customers who don’t have access to put solar panels on their own house a chance to still subscribe to a solar program,” said Mark Stutz, spokesperson at Xcel Energy’s Denver office. While the utility opposed the renewable energy standard when it was being pushed by Colorado residents in 2004, Stutz says that was a mistake. “We found out pretty quickly that our customers wanted renewable energy.”

Today, about 18 percent of Xcel’s sales come from renewable energy sources – including 150 megawatts from decentralized solar at the end of 2012 – and it expects to hit the state mandate of 30 percent a few years before the 2020 deadline. Already it has entered into partnerships with two solar gardens of 9 megawatts each. “I think utilities are more and more interested in this model,” Hughes said. “It turns out to a great compromise between solar advocates and utilities. That’s one of the things that’s so nice about it. … The key is it increases the fairness of solar.”

The concept is not unknown in San Antonio, either.

Recently, Sinkin brought a Colorado outfit called the Clean Energy Collective to pitch CPS Energy on the solar garden model of community power. San Antonio benefits from a publicly owned utility that must be more responsive to its customers, Eugster said, which explains why San Antonio is leading the state in solar power – with 45 megawatts in centralized systems and 10 megawatts spread across the rooftops – despite the absence of any state mandate to do so.

The Texas Legislature failed again this year to add a specific solar “carve-out” to the state’s Renewable Portfolio Standard. “Pretty much everything has been stymied,” said Russell Smith, executive director at the Texas Renewable Energy Industries Association. “Clearly, if you have a standard for decentralized solar, you’ll make more progress. We’ve tried to get a standard for non-wind renewables for the past three or four biennial sessions.”

If solar boosters like solar gardens for their ability to take the low-carbon technology into low-income communities, Eugster likes the arrays as a “better fit” with CPS’s business model because the utility can set them up rather than leaving installation to individual homeowners.

Surveying San Antonio’s solar scene though an environmental lens, Annie Lappé, policy director at Vote Solar, a pro-solar non-profit, says the real issue is that there is only one financing option available to those who want sun power: owning your own system. “There are definitely some barriers to entry that could be changed through access to more innovative finance models,” she said. Ultimately, those who don’t own their own home – or don’t have a solid line of credit – are excluded.

For groups like the Southwest Workers Union, a San Antonio-based social justice nonprofit that was deeply involved in the energy debate around the time the city’s solar program was first being organized, that shortcoming is still an issue. “It’s no secret that many low-income folks don’t own their homes or many live in apartments or live on paycheck to paycheck,” Diana Lopez, an environmental justice organizer at SWU, said by email. “We support a solar program that benefits everyone and allows people of all income levels and housing to be part of it. How to engage those neighborhoods is something that needs to be addressed openly and in a community setting.”

Revolutionaries and stranded ratepayers

Utilities around the country are of differing mindsets about what is coming to be called the “democratization” of energy: decentralized, renewable power generators, producing modest amounts of electricity (typically under 5 kilowatts), which are used at or near the point of production. Some see the changes as irreparably at odds with the traditional utility structure that has hinged on large-scale, centralized power plants producing hundreds of megawatts of electricity to be shipped over long distances by high-capacity power lines.

San Antonio’s introduction to the payment-cutting SunCredit system, for instance, came two months after the release of a report on the subject by the Edison Electric Institute, a trade organization representing publicly owned utilities. While noting that decentralized renewable energy represents only 1 percent of electric utilities’ “lost load” nationwide, it calls rooftop solar and similar technologies a “disruptive force” in the industry and draws ominous parallels to Kodak, driven into bankruptcy, and to the U.S. Postal Service, pushed near to bankruptcy, by the rise of digital technologies. In a clarion call about the new technologies, the report urges utilities to immediately institute a monthly customer service charge “in order to recover fixed costs.” It further recommends reining in “cross-subsidy biases” – the imbalance alleged by CPS through which low-income residents increasingly foot the bill for upper-income customers – which the report’s author considers inherent in energy efficiency and decentralized, renewable energy systems.

A “disruptive force” for San Antonio’s electric utility? Rooftop solar installations have increased rapidly in the CPS service area in recent years but their overall number remains relatively small

Making CPS Energy’s case, Eugster said that as long as solar users are tied into the electric grid they are receiving benefits from the utility they are not paying for. “The problem is, they are still using power at night, in the morning hours, when it’s cloudy. Eighty percent of the hours of the year that customer is using the utility,” he said. “The way our rate strategy is designed we don’t recover that cost. That’s the challenge we’re trying to address.”

While there is one flat fee of $8.25 per CPS utility bill for service, that fee does not cover the cost of maintaining the utility’s poles and wires, much less begin to pay down the debt on long-term investments like the new billion-dollar coal plant that went online in 2010. Large-scale investments like that are typically paid down over 40 or 50 years, or more, Eugster said. “Those are billions of dollars that are there that have services associated with them that need to be paid.”

Sinkin argues that the positive impact of those thousand solar arrays are a net benefit to the utility by reducing the amount of power the utility needs to purchase or generate itself, reducing pressure to construct new power plants, easing the strain on the utility’s grid by generating power that is mostly used at the point of production, as well as helping clear the air by reducing the need for electricity from more polluting energy sources and cutting carbon dioxide emissions tied to global warming.

He said it’s far too soon to suggest that any one group is propping up another – that it won’t become a measurable issue until the penetration by decentralized solar reaches levels now being seen in San Diego, where up to a quarter of the peak-load energy is generated by rooftop and small-scale solar. “That’s where the problem comes in. Twenty-percent penetration. I think San Antonio is at point-two-percent penetration,” Sinkin said. “We didn’t need to solve this in seven weeks – maybe in seven years it will be a problem.”

“I don’t think anyone knows what that tipping point is,” Eugster responded. “Right now the numbers we’re talking about are still relatively small, but solar prices are coming down, there are new models coming in place, there are leasing models, and so it could get bigger a lot faster.”

Eugster’s message echoes the Edison report’s warning of a possible “vicious cycle” developing in the energy sector. As more customers move to renewables, the argument goes, the “stranded costs” of a utility’s centralized infrastructure that are borne by low-income customers will increase. Faced with the rising price of electricity from the utilities and lured by falling renewable energy prices, even more customers are expected to jump ship on the utilities.

However utilities respond to alleged “cross-subsidies,” the price of solar is definitely falling, making it an increasingly attractive option. Across much of the Southwest, solar is already competitive with gas and coal power. Recent predictions from investment bank Citigroup suggest it could reach as low as 25 cents per watt by 2020.

Driven by the same sorts of concerns that had CPS seeking to cut its net metering program, San Diego Gas & Electric proposed imposing a “network usage” fee on customers with rooftop solar in 2011. The move was rejected last year by the California Public Utilities Commission, which suggested it was at odds with state laws seeking to encourage decentralized solar.

Vote Solar’s Lappé called the economic justice argument made by utilities about “cross-subsidies” a “red herring.”

“The way rates are structured right now, there are inherent cross-subsidies in the rates,” Lappé said. “When it’s something [utilities] like, they call it ‘cost-sharing,’ but when it’s something they lose money on, they call it a ‘cross-subsidy.’ … What this is really about is lost revenue. And we are saying that net metering and adding this valuable and clean local power to the grid is really a cost-gift, if anything, because the benefits outweigh the costs.”

Solar arrays atop homes in Germany

If utilities in the United States are having a hard time getting used to decentralized power, they are not alone.

Germany’s energy revolution, known as the Energiewende, or “energy transition,” rocketed a nation about the size of Montana with sunlight resources equivalent to Alaska’s from 32 megawatts of renewable energy in 1999 to 30,000 megawatts last year. According to investigative reporter Osha Davidson’s recent book, Clean Break: The Story of Germany’s Energy Transformation and What Americans Can Learn From It, the increase didn’t come because of the utilities. “Our big utilities completely ignored renewables,” Rainer Baake, one of the Energiewende’s authors, is quoted as saying. In fact, if individuals and small co-ops hadn’t taken charge, Davidson writes, “renewable power would still be a novelty” in the nation now leading the world in green power.

Government policies that allowed individuals and small groups to get a fair price for the power they sent back to the grid, through Feed-In Tariffs, set the stage. But it has been individual homeowners, strategic cooperatives, and communities themselves that led the way and that now own 65 percent of the country’s renewable power sector, according to Davidson. The utilities own a scant 6.5-percent share.

‘Death spiral’

John Farrell, director of the Energy Self-Reliant States and Communities program at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, a national research and policy organization, said few utilities are doing the work needed to remain relevant, avoid bankruptcy and prevent stranding their customers with decades of debt from major fossil-fuel investments.

“The model has to change. If we don’t change anything those utilities will probably go bankrupt, especially if they keep investing money in the same way and trying to make their buck by building more infrastructure. Because we don’t need the big power plants, and we don’t need the big transmission lines to carry that power, they don’t have a way to make a return other than that,” Farrell said. “The only other thing they have is energy sales and when we do net metering it comes right out of their bottom line. So from an accounting perspective, I buy their argument, this is the death-knell of their model. From a social benefit and energy cost-effectiveness to ratepayers argument, I think they’re full of crap and this is really just about playing defense for their bottom line.”

[Related coverage – TCN Interview: John Farrell]

CPS Energy’s $1-billion, 750-megawatt Spruce 2 coal plant went online in 2010 as similar projects were being cancelled elsewhere. Only one new coal plant went online last year in the United States and plans are stacking up for the retirement of coal plants across the country. While there have been no coal plants built so far this year anywhere in the U.S., according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, energy demand has so far been met by 21 solar farms, 18 landfill gas projects, and five natural gas plants.

Recent developments in Texas are illustrative. When plans were scrapped in February for a 1,200-megawatt facility in Matagorda County called White Stallion Energy Center, with them went Texas’ last active proposal for a traditional coal-fired power plant. White Stallion CEO Randy Bird blamed “regulatory barriers” and low-priced natural gas. When Nebraska-based Tenaska abandoned its proposal for a carbon-capturing coal plant near Abilene last month, the company said it would henceforth focus on natural gas and renewable sources to generate electricity. Plans for Summit Power’s “clean coal” power plant in West Texas remain in play.

Even with the 2010 start-up of its new coal plant, CPS is by no means a backwards utility when it comes to cleaner power sources, as the utility’s Eugster or the solar advocate Sinkin will tell you. Before the latest flare-up over the SunCredit plan, Sinkin said he was writing the utility “love letters” because he felt their solar ambitions were so closely aligned. The utility was rich in wind power even before the collapse of negotiations for an expanded nuclear investment under the weight of public protests and lawsuits in 2009. In fact, as Eugster points out, the utility has become a prominent example of a traditional power company in transition: “We are doing a lot in moving the utility to a model of the future, not just one that’s stuck in the past. One that embraces renewables, has it part of the mix, diversification, new technology, new innovation.”

CPS is co-owner of the South Texas Project nuclear plant in Matagorda County. But with its withdrawal from a planned, two-unit expansion there – plans picked up by Toshiba Corp., only to be rejected by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in April – CPS began shifting its power-producing strategy. That new tack has included investing deeply in efficiency measures; announcing the early retirement of its dirtiest coal plants, expected by 2018; and striking deals for centralized solar projects, the most notable a 400-megawatt deal with Korean-based OCI Solar that broke ground in March. More recently, a purchase power agreement was struck with Summit Power for electricity from its coal-gasification plant, being designed to capture 90 percent of carbon emissions. CPS also bought a natural gas plant. Meanwhile, leaders at City Hall were getting versed in decentralized energy futures as laid out in San Antonio’s new sustainability plan, known as Mission Verde.

Larry Zinn, chief of staff for Castro’s predecessor, Mayor Phil Hardberger, hoped to see abandoned schools across the city rejuvenated by neighborhood solar projects, green-tech job training and community gardens. But even he sensed it might not come easily, as he hinted in a TedX talk he gave in December, 2010:

“People are going to be creating their own electricity. They’re going to be energy distributors in this sense. Utility companies are going to become less generators of power and electricity and more traffic cops of it. They may own the smart grid but they may not own the energy that’s produced. In fact, they may be paying you.”

Under the coming energy reality, Zinn said, CPS Energy could ultimately end up in competition with itself as one part of the utility tries to sell power to residents and another is required to buy energy from them (or simply manage the electricity in storage facilities). “It’s going to have to change its business model,” he said. “And this is true of utilities all across the country. These changes are coming. Mission Verde is built on this foundation and it is not something really unique because it is something that is going to be happening all across the world. We simply need to join that movement and also figure out a way, perhaps, to lead it.”

Even as utilities feel increasingly besieged by changing technology, they’re also being challenged by coevolving knowledge of the disruptive power of a destabilized climate system.

In the wake of Hurricane Sandy, which robbed more than 8 million Eastern Seaboard residents of electricity, some for weeks, the American Solar Energy Society dedicated a full day of its April convention to conversations about renewable power and security. After all, energy security involves more than domestically produced oil and natural gas. It can also mean resilient solar resources, distributed evenly throughout a community, to run medical devices, heat or cool homes, and purify drinking water after extreme weather events, which scientists project will be more destructive as climate change progresses.

But even as technological abilities and understanding of evolving challenges advance, discussions about the implications for the fundamental mission and responsibilities of electric utilities don’t appear to be happening, Lappé said.

“The second point [of the Edison Electric Institute paper], which they really didn’t elaborate on and really needs a lot more research, is, ‘How are the utilities really going to fundamentally adapt so they can provide more value to their customers in this decentralized model of the future?” she said. “That death spiral the EEI paper talks about is a real potential threat to their business model, but businesses have to adapt, they have to change as technologies grow and become accessible. We’re just sitting in the middle of the storm as this is happening. It’s going to be an interesting decade.”

+++++

Greg Harman is an independent journalist based in San Antonio. He was editor of the weekly San Antonio Current from 2010-12 and a staff writer for the Current from 2007-10. His writing has also appeared in publications including the Houston Press, Houston Chronicle, Texas Observer, Austin Chronicle, Fort Worth Weekly and Odessa American. Links to a selection of his work can be found at Harman on Earth.

+++++

Editor’s note: Generous donations from readers made this article possible. Please consider a tax-deductible contribution to help Texas Climate News continue producing non-profit, independent journalism in the public interest.