After nearly an entire legislative session’s worth of policy discussion and political maneuvering, Texas lawmakers acted late Wednesday night to allocate $2 billion from the state’s Rainy Day Fund for water infrastructure and conservation projects, contingent on voter approval of a constitutional amendment this fall.

After nearly an entire legislative session’s worth of policy discussion and political maneuvering, Texas lawmakers acted late Wednesday night to allocate $2 billion from the state’s Rainy Day Fund for water infrastructure and conservation projects, contingent on voter approval of a constitutional amendment this fall.

The votes in the state House and Senate, elements of a complex budget deal, represented a dramatic turnaround in the Legislature’s posture toward Texas’ water needs.

Despite repeated warnings that the state’s water supplies are on a collision course with population growth and with a drier, hotter future climate projected by scientists, lawmakers in recent sessions had not voted to fund a broad array of water projects, as recommended by the Texas Water Development Board and others.

Then came the record-setting drought and heat wave of 2011 with massive impacts including billions of dollars in agricultural losses, historic wildfires, urban water restrictions across the state, and the deaths of millions of trees. Then, over the past two years, drought conditions have lingered throughout much of the state, with warnings by the state climatologist that such conditions could drag on for years to come.

It was evident in the lopsided House and Senate votes on the $2 billion water deal Wednesday that lawmakers had paid heed. But will Texas voters do the same, come November?

Judging from the results of an opinion survey that was conducted by Texas A&M University researchers in February and March and released last month, they will.

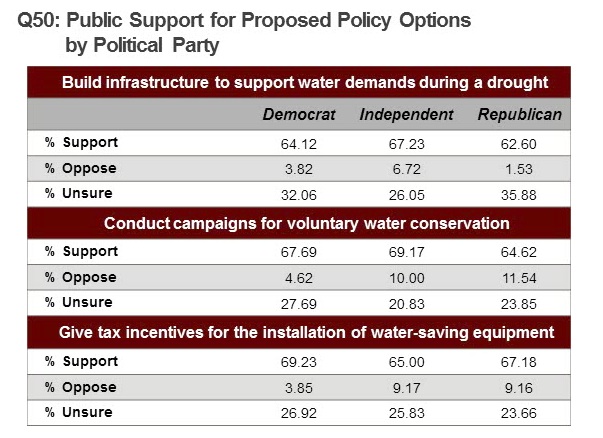

The poll did not ask specifically about the constitutional amendment that voters will be asked to approve to create a new funding mechanism for the $2 billion in spending. But the findings included overwhelming, almost identical levels of support among Republicans, Democrats and Independents for policy options including “build[ing] infrastructure to support water demands during drought.”

Altogether, 64 percent of the survey respondents backed new infrastructure, while just under 4 percent were opposed. Support ranged from Republicans’ 62 percent to Democrats’ 64 percent to Independents’ 67 percent. Similar levels of support from the three political categories were voiced for conservation-related policies.

“If the [vote on] this constitutional amendment were held tomorrow, it would pass strongly,” said the survey leader, Arnold Vedlitz, director of the Institute for Science, Technology and Public Policy (ISTPP) in Texas A&M’s Bush School of Government and Public Service. Vedlitz spoke to Texas Climate News about the survey on Wednesday, a few hours before the legislative action to move ahead with the water proposal.

“There’s broad and deep support among the Texas citizenry for the government taking action to solve our water shortfall problems,” he added. “They want the government to do something and they’re expecting it to do something, like building infrastructure.”

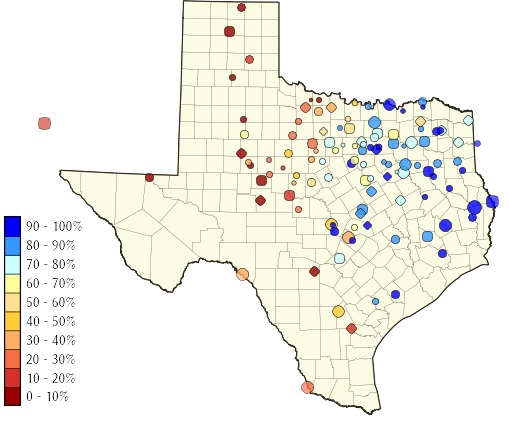

Vedlitz elaborated on his appraisal of the survey results: “People are extremely concerned about water and they’re concerned not out of some abstract [. Two thirds to three quarters of the people have experienced drought in their communities in the last two years. So it’s not some imaginary hypothetical problem. They’ve actually seen it, they’ve faced it .”

Regarding the uniformly high support for infrastructure and conservation measures among all political groups, he said: “People want their state to have the water resources to do the things they think are important – to support cities, to support industry, to support private uses, to support agriculture, to support environmental needs. They want it and they’re willing to pay for it.”

Vedlitz said he thought it was particularly significant that survey participants were not willing to abandon the water needs of the environment and agriculture. “That’s a really important finding,” he said. “People are concerned about quality of life and they want to support everything.”

Respondents, for instance, overwhelmingly said they were willing to conserve water to help protect the environment (72 percent) and Texas agriculture (71 percent). “Protect[ing] water resources to preserve wildlife and fishery habitats gained the greatest overall support (70 percent) in a list of policy options that included the infrastructure question.

Solid majorities of poll participants said they were willing to pay more on their monthly water bill “to guarantee a secure water supply in your area” – 69 percent to accept an increase of $1 to $5 and 58 percent an increase of $6 to$10.

At the same time, the findings suggest, as have other recent opinion polls, that the strong skepticism about manmade climate change that has been embraced by many political conservatives in recent years could be waning somewhat in that ideological camp.

Texas, of course, is a notably conservative state on balance, with substantial doubts about the overwhelming scientific consensus on climate change’s human causes voiced by key conservative officeholders such as Gov. Rick Perry.

When the Texas A&M survey asked about the “causes of drought or water shortages,” however, 59 percent said climate change was one of them. That was below the 84 percent who said “short-term changes in annual rainfall” and 66 percent who said “increased demand from water users,” but above the 51 percent who said “overuse of water” and the 47 percent who said “inadequate management of water resources.”

Criticism of the Legislature’s water proposal came from some lawmakers in the Republican Party’s fiscally frugal Tea Party faction. If opponents of the constitutional amendment to spend the $2 billion are hoping for a meteorological turn in a notably wet direction in coming months to help persuade voters to defeat it, however, they won’t find any solace in recent climatological reports.

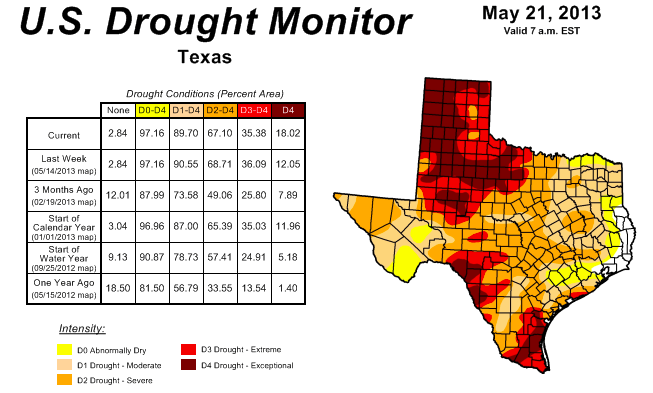

Within hours of the lawmakers’ action, the U.S. Drought Monitor project issued its latest weekly report, showing that less than 3 percent of Texas was not experiencing dry conditions in one of the categories ranging from “abnormally dry” to “exceptional drought.” Almost 90 percent of the state was affected by drought to one degree or another, the report indicated.

In its latest Southern Plains Drought Outlook, issued [PDF] last week, the National Weather Service’s Regional Operations Center in Fort Worth ticked off some of the effects of the state’s continuing drought:

- On Texas farms, 73 percent of winter wheat was in “poor to very poor condition,” the largest percentage in the nation.

- Texas “will likely enter the summer of 2013 with the least stored water in at least 25 years”

- The water level in reservoirs statewide stood at 66 percent – 12 percent less than same time in 2012. [The percentage still stood at 66 a week after the Weather Service report, according to the Water Development Board.]

A map accompanying the report showed drought conditions expected to persist or intensify in roughly the western half of the state, with “some improvement” in continuing drought in about a fourth in the middle, and easing of drought impacts in the remaining fourth to the east.

The report forecast below-normal precipitation in the western part of the state with equal chances of above- or below-normal rainfall in the rest. It warned, however, about “increased chances for above-normal temperatures” in Texas and other Southern Plains states, adding that higher temperatures will mean increased evaporation of any ran that does fall, further reducing reservoir levels.

– Bill Dawson

+++++

Editor’s note: Arnold Vedlitz is a HARC Fellow. HARC, the non-profit, non-partisan organization incorporated as Houston Advanced Research Center, publishes Texas Climate News. TCN is independently written and edited by journalists who are not HARC employees and who make all editorial decisions without direction or influence by HARC, its funders or affiliates.