Texans who don’t like the current, record-setting drought – and we’re going to venture one of TCN Journal’s extremely rare guesses that most Texans don’t like it – won’t be pleased by a pair of future-gazing reports that came out this month.

One was the latest seasonal drought outlook from the National Weather Service. The second was the official summary of an upcoming report on climate change and extreme weather events and disasters from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The time scales of the two reports are very different. The drought outlook offers a forecast for the next three months. The IPCC report maps computer models’ projections of drought-related conditions in the second half of this century.

In both cases, however, the message for Texas is the same: More very dry conditions lie ahead.

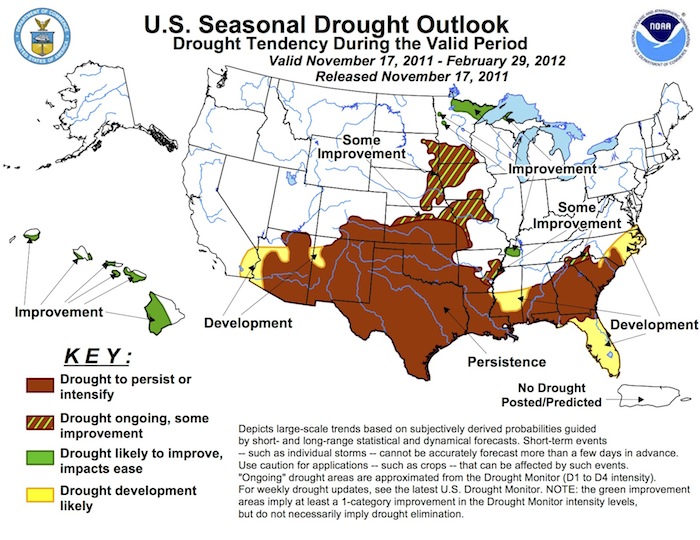

The map accompanying the National Weather Service forecast for the period through next Feb. 29 indicates that drought conditions are expected to “persist or intensify” across all of Texas and virtually all of adjoining Oklahoma, Louisiana and New Mexico, as well as in a number of other nearby states.

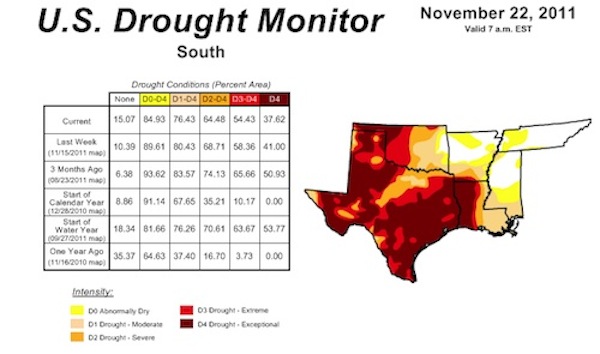

The latest U.S. Drought Monitor map, produced by a consortium of government and academic experts, shows most of Texas remains in “exceptional” (the worst) drought conditions.

John Nielsen-Gammon, the Texas state climatologist (whose insights have been much in demand lately as the drought drags on), offered these pessimistic observations to The Daily Climate, a non-profit news outlet:

In Texas, a dry winter won’t be devastating, said Nielsen-Gammon, the climatologist. But it will set the state up for a horrid spring.

Winter is normally a time of recharge, he said: With landscaping and agriculture demands dormant, soil moisture gets recharged and reservoir levels go back up.

“That’s probably not going to happen,” he said. And so the state risks repeating last year’s big wild fires next spring, and growers risk another year of failed or reduced crops.

Nielsen-Gammon presented [PDF] this outlook to state lawmakers in a report about the 2011 drought to the Legislature, issued Oct. 31:

Because of the return of La Niña conditions in the tropical Pacific, a second year of drought in Texas is likely, which will result in continued drawdown of water supplies. Whether the drought will end after two years or last three years or beyond is impossible to predict with any certainty, but what is known is that Texas is in a period of enhanced drought susceptibility due to global ocean temperature patterns and has been since at least the year 2000. The good news is that these global patterns tend to reverse themselves over time, probably leading to an extended period of wetter weather for Texas, though this may not happen for another three to fifteen years. Looking into the distant future, the safest bet is that global temperatures will continue to increase, causing Texas droughts to be warmer and more strongly affected by evaporation.

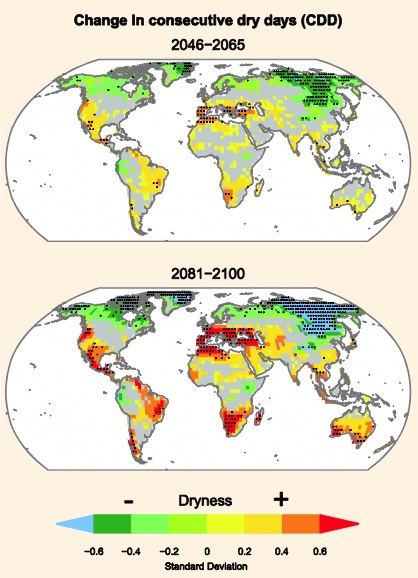

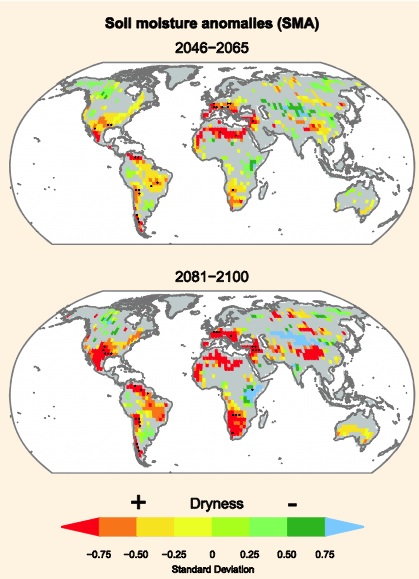

Looking down the road just a few decades, more of the same appears to be in store, as portrayed by these maps in the IPCC report on the impact of manmade climate change on extreme weather events. Increased dryness is shown in yellow to red shades.

The first maps show the areas of the world (including Texas and surrounding areas) where the number of “consecutive dry days,” with “dry” defined as less than one millimeter or precipitation, is expected to increase from 2046 to 2065 and from 2081 to 2100, compared to late-20th-century conditions.

The second maps show areas where soil moisture is expected to decrease in the same periods. In both cases, the driest conditions – shown in orange and red – are expected in the latter part of the century. Colors were added in regions areas where at least two-thirds of computer model projections (12 of 17 for dry days, 10 of 15 for soil moisture) were in accord on the direction of the expected change.

The Reuters news service gave this overview of the IPCC report, the full version of which is scheduled to be published in February:

An increase in heat waves is almost certain, while heavier rainfall, more floods, stronger cyclones, landslides and more intense droughts are likely across the globe this century as the Earth’s climate warms, U.N. scientists said [on Nov. 18].

The [IPCC] urged countries to come up with disaster management plans to adapt to the growing risk of extreme weather events linked to human-induced climate change, in a report released in Uganda ….

The report gives differing probabilities for extreme weather events based on future greenhouse gas emissions scenarios, but the thrust is that extreme weather is likely to increase.

“It is virtually certain that increases in the frequency and magnitude of warm daily temperature extremes … will occur in the 21st century on the global scale,” the IPCC report said.

“It is very likely that the length, frequency and/or intensity of warm spells, or heat waves, will increase,” it added.

The IPCC report, produced by 220 scientist authors from 62 countries, is consistent with the outlook of drier conditions for many areas that has been expressed in other recent studies, such as one by scientist Aiguo Dai of the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Colorado, issued in October 2010.

In announcing the study, NCAR said Dai’s analysis showed that the U.S. and many other populous nations “face a growing threat of severe and prolonged drought in coming decades,” and “that warming temperatures associated with climate change will likely create increasingly dry conditions across much of the globe in the next 30 years, possibly reaching a scale in some regions by the end of the century that has rarely, if ever, been observed in modern times.”

“We are facing the possibility of widespread drought in the coming decades, but this has yet to be fully recognized by both the public and the climate change research community,” Dai says. “If the projections in this study come even close to being realized, the consequences for society worldwide will be enormous.”

While regional climate projections are less certain than those for the globe as a whole, Dai’s study indicates that most of the western two-thirds of the United States will be significantly drier by the 2030s. Large parts of the nation may face an increasing risk of extreme drought during the century.

Other countries and continents that could face significant drying include:

- Much of Latin America, including large sections of Mexico and Brazil.

- Regions bordering the Mediterranean Sea, which could become especially dry.

- Large parts of Southwest Asia.

- Most of Africa and Australia, with particularly dry conditions in regions of Africa.

- Southeast Asia, including parts of China and neighboring countries.

– Bill Dawson