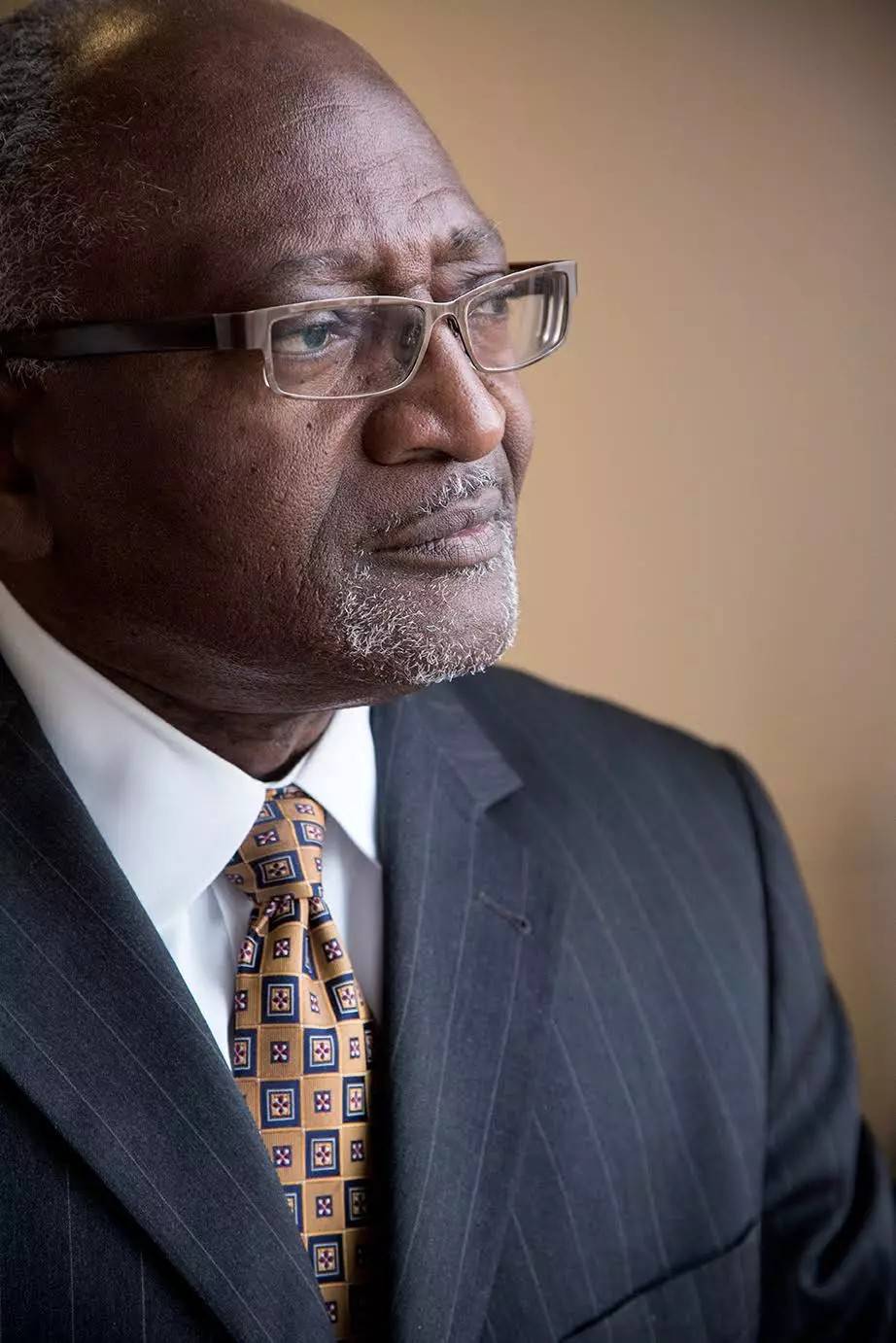

Robert Bullard of Texas Southern University, “father of environmental justice,” assesses the swelling anti-racism movement and the campaign to link environmentalism with racial and social justice. First of a two-part interview.

Robert Bullard of Houston is a sociologist and a civil rights and environmental activist, often called “the father of environmental justice.” He earned that recognition because of the crucial role he played over decades in researching and calling attention to racial and economic inequities that contribute to disproportionate pollution and climate-change impacts.

Robert Bullard of Houston is a sociologist and a civil rights and environmental activist, often called “the father of environmental justice.” He earned that recognition because of the crucial role he played over decades in researching and calling attention to racial and economic inequities that contribute to disproportionate pollution and climate-change impacts.

Since 2016 Bullard has been the distinguished professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University, a public, historically black university in Houston. Previously, his numerous academic positions included service as dean of Texas Southern’s Barbara Jordan-Mickey Leland School of Public Affairs from 2011-2016 and as Ware distinguished professor of sociology and director of the Environmental Justice Resource Center at Clark Atlanta University from 1994-2011.

Bullard’s 1990 book, Dumping In Dixie: Race, Class, And Environmental Quality, was a seminal examination of five African-American communities in Houston, Dallas, West Virginia, Louisiana and Alabama that were inspired by the civil rights movement to link environmentalism with appeals for racial and social justice.

Expressing a theme that ran through his later work as a scholar and activist, Bullard wrote in that book:

Ineffective land-use regulations have created a nightmare for many of Houston’s neighborhoods – especially the ones that are ill equipped to fend off industrial encroachment. Black Houston, for example, has had to contend with a disproportionately large share of garbage dumps, landfills, salvage yards, automobile ‘chop’ shops, and a host of other locally unwanted land uses. The siting of nonresidential facilities has heightened animosities between the black community and the local government. This is especially true in the case of solid-waste disposal siting.

Bullard talked with Texas Climate News editor Bill Dawson on June 10, one week after 60,000 people marched in Houston to protest the killing by Minneapolis police of Houston native George Floyd, whose childhood home was an apartment in a public housing complex across the street from the Texas Southern campus.

This first part of the interview features Bullard’s thoughts on the enormous movement for racial justice that has arisen from Floyd’s death, his recounting of the history of the environmental justice movement, and how the two movements relate to one another. The second part of the interview presents his reflections on the Trump administration’s impacts on preceding actions to advance environmental improvement and environmental justice and his hopes for what the 2020 election could bring. The interview has been edited for clarity.

+++

As a veteran scholar of harms rooted in racism and socioeconomic inequity and as an activist yourself, often called the father of environmental justice, did the extraordinary scope of this outpouring of anger and grief and political energy that we’ve witnessed over the last week or so surprise you in any way – that it was so huge, so profound?

I must say that I was a bit shocked. And amazed and hopeful that this moment in our history could be that turning point, could be that tipping point, could be that really important period in our history that we have decided – and it’s a collective we, the various generations that are out there marching and protesting, that are voicing, that are doing all kinds of actions – that this is a moment in time that we’re not going to let these artificial barriers that have been so ingrained in our society, in our country’s DNA, hold us back.

I came out of the ’60s. Students, we were very optimistic, and we were fearless in terms of facing down police who were brutal and their dogs and water hoses, etc. That modern civil rights movement in the ’60s that spilled over into the ’70s was a large movement. But it somehow did not capture a huge segment of our society that basically saw civil rights as no problem, saw racism as no problem, saw Jim Crow as no problem, simply because the vast majority were not discriminated against and were not black.

So when you look at those images across the television screen, or if you’re out there, you see that it looks nothing like the groups that were out there getting mowed down by police in the ’60s. I don’t know when it actually occurred. Probably there has been some transitioning. Maybe Covid has something to do with it. Maybe the lockdown has something to do with it. Maybe the fact that people are at home and had time to think.

Those images that came across the television screen with George Floyd being just lynched on national TV, I think they touched the souls and hearts and minds of a lot of people that all these other killings and the brutal murders didn’t. Somehow this seems different in the channeling of the young people’s energy.

We had white students and other white people coming down [South to join civil rights protests] in the ’60s, but this seems different. It’s almost like people are saying we’ve got to do this at home because we can’t look 3,000 miles away and say, oh it’s down in Mississippi. It’s also in Minneapolis. It’s in Detroit. It’s in Chicago and L.A. It’s in Atlanta. It is taking a national approach to the issue of systemic racism and how we’re going to address this. The triggering point, I think, was looking at police violence.

As a sociologist looking at social movements, I’m seeing the demographic shift in the country. My generation, the baby boomers, we’re outnumbered now by millennials. Then if you move below the millennials to the next generation down, all the way down to kids in high school who are not even old enough to vote, they’ve been activated and politicized. Their awareness is at the level of when I was in college in terms of understanding how things are connected in different political and economic dynamics.

As a sociologist looking at social movements, I’m seeing the demographic shift in the country. My generation, the baby boomers, we’re outnumbered now by millennials. Then if you move below the millennials to the next generation down, all the way down to kids in high school who are not even old enough to vote, they’ve been activated and politicized. Their awareness is at the level of when I was in college in terms of understanding how things are connected in different political and economic dynamics.

To a large extent it’s because of our technology and the ease in which information can be transmitted via cell phones and iPads, etc. And the extent to which these young people have news and other information at their fingertips and can get it in real time, and can organize, mobilize, and don’t have to wait for the 6 o’clock news or whatever. That’s a sociological shift in information as power, and how that information can be used to get people mobilized.

I thought something like that would happen after Sandy Hook with all the gun violence and school shootings and killing. If we couldn’t get mass mobilization around killings of kids in elementary school and kindergarten, what can raise the consciousness of this country that something needs to happen when it comes to the violence that’s generated by guns and the lack of movement by our Congress and our legislatures? It just kind of petered out. We didn’t have the mass demonstrations like we have now, and they’re happening over long periods of time.

The other thing that’s different that I see, looking at this as a sociologist – this social movement, the people who are pushing for change – is there is an urgency in the air, and the urgency is driving an agenda where people are saying no, no, no, we do not want to wait another 20 years or 15 years or whatever to get legislation, to get change.

People in my generation had to fight and fight and then we had to compromise and then settle for incremental. [Now] the incremental is the starting point, and not the finish line, for people out there protesting. We’re talking about transformative change, not just moving the chairs on the deck but really reorganizing, real change, really shifting resources within police departments.

And it’s really gotten politicized to the point where people are talking about generally defunding the police and no police. We know that there has to be some policing, there has to be some law enforcement, unless we’re going to say we’re committing to no crime, or no violent crime, whatever. But again, the idea of shifting funds to where priorities are and demilitarizing the police, because you know, why does a police department need a tank? It’s like, well, come on now.

So those concepts are now being pushed into common thinking, whereas four or five years ago, people would say, well, you know, the police department needs to be well equipped and didn’t question whether or not they need all of these assault weapons and tanks and armor. Almost like they’re going to Iraq when they go to, you know, Chicago. And it’s like, who is the enemy? That’s changing, that’s shifting.

And I’ll tell you another big change. When polls five or 10 years ago asked, is discrimination a major problem in our society, is discrimination against blacks a problem, 75 percent of black people would say yes. That number has stayed pretty consistent. The white people over the years, the numbers will come back that it’s not a problem. You might get a third of white people saying racism is still a problem and discrimination is a problem. And then you’d get about a third of white people who say racism and discrimination against whites is probably on par with blacks.

But today, when those polls are coming out, you get totally different numbers. A majority of whites say that racism is a problem, discrimination is still a problem, as opposed to this thinking that somehow the 1964 Civil Rights Act just eliminated discrimination and it’s no longer a problem.

It is still a problem. It’s still systemic. And it runs through almost every institution in our society. That’s another shift. And I think a lot of it has to do with the demographic shift, but also the age cohort shift in terms of younger people having fewer wedge issues that drive them to the right. In terms of issues around guns, issues around abortion, and issues around same-sex marriage, issues around marijuana, you start looking at those things and these young people say, well, what’s the problem?

I’d like to learn your thoughts about how this historical moment intersects with, and may influence, the movement that you’re so closely associated with – environmental justice, as it was first called. Of course it’s been supplemented since then by appeals for climate justice. I think even some people interested in climate change and environmental issues may not quite understand what people mean by environmental justice or climate justice. I recall, going back some years, that people were initially calling attention to what they called environmental racism. Then the terminology seemed to shift, not to replace environmental racism but to be dominated more by discussion of environmental justice and more recently climate justice. Please tell me if I’m wrong about this evolution of terminology, but if I’m right, how is environmental justice different from environmental racism? How would you describe the arc of the history of this movement, this consciousness?

Well, when I was doing the study in Houston looking at landfills, that was 1979 and there was no concept of environmental justice. There was a discrimination case of locating landfills in black neighborhoods just because the neighborhoods were black – that was a form of discrimination – Bean vs. Southwestern Waste Management Corporation. There was no national movement in 1979. There was not a national movement until the early ’80s – 1982, ’83.

When this company dumped oil that was contaminated with PCBs along the highways in North Carolina and the government decided they wanted to scoop it up in 1978, they scooped it up and then needed a place to put it. In 1982 they dumped it in Warren County, which is one of the poorest, blackest counties in the state. Rev. Benjamin Chavis and the United Church of Christ Commission for Racial Justice organized protests in North Carolina. The NAACP, the Congressional Black Caucus, they organized, and that’s when the term environmental racism was coined. That’s when there were protests – over 500 people went to jail from ’82 to ’83. The birth of the environmental justice movement nationally was out of that fight against environmental racism in North Carolina.

So the case that I had, Bean vs. Southwestern Waste Management Corp. [involving the siting of a landfill for garbage], was the first environmental discrimination case using civil rights law. The concept was fighting discrimination. The environmental justice movement grew out of a fight against racism, and it was a civil rights issue, so the environmental justice movement was embedded in civil rights and fighting discrimination.

We started to look at various issues around the country. I started to expand my Houston study to look at Dallas, and the lead smelters, and Louisiana’s cancer alley with chemical plants, and the largest hazardous waste facility in the country located in the Alabama Black Belt. And then the only place [in the U.S.] that manufactured the chemical that killed all those people in Bhopal, India – methyl isocyanate – Union Carbide [in the largely black community of Institute, W. Va.].

When I did Dumping In Dixie, that was a racial justice, environmental justice book. We weren’t dealing with white people communities that were being poisoned, dumped on, etc. The way that environmental justice expanded out from environmental racism is, as we started looking at justice questions, all communities that were being dumped on did not happen to be black. So we started expanding out to Native lands – reservations, along the U.S.-Mexican border in terms of Hispanics, Latinos, Asian and Pacific Islanders.

We had the ’91 People of Color Summit that brought together people of color from all over the country to talk about environmental racism and environmental justice. It was a four-day summit, and the first two days were just people of color. It was just to unpack the baggage that people of color were saddled with because of slavery, imperialism, Jim Crow, exploitation. In the last two days, we brought everybody in and said we want to build a movement that was inclusive, that did not discriminate, and if white communities were poisoned, polluted, dumped on, etc., we wanted to bring them in too.

That’s when we started to expand environmental justice onto a national scene that included any communities that were being impacted disproportionately because of their race, their income or their physical location. We developed 17 principles of environmental justice, and environmental justice became the larger framing for our movement. But that did not mean that we were not still concerned about environment racism, because environmental racism was rampant wherever people of color were being targeted.

Environmental justice was what was happening in Appalachia, for example, mountaintop removal. That was not racism. They were being dumped on because they were poor whites that didn’t have power. And so we framed it in a way that environmental justice was the larger theme. Where there was environmental racism we called it what it was, environmental racism, and with a racial justice lens and a civil rights lens.

The same thing is true with climate change. For a long time, a lot of the climate scientists and the climate policy folks saw climate change more in the context of climate change being, and policy being, parts per million and greenhouse gases. The vulnerability part was not really lifted up.

The same thing is true with climate change. For a long time, a lot of the climate scientists and the climate policy folks saw climate change more in the context of climate change being, and policy being, parts per million and greenhouse gases. The vulnerability part was not really lifted up.

Those of us who came out of environmental justice, as we moved into those spaces where people were talking about climate change, which were all-white spaces, we brought to the table this whole idea that if you are to address climate change, you have to expand your definition of what climate change is.

And in terms of responsibility, who has been the most responsible for the problem? The cause of the problem? And then, which communities and nations are the most vulnerable when it comes to the negative climate impacts? And what we’re saying is, if you don’t address the issue of responsibility – who created the problem – and vulnerability – who’s going to be impacted first, worst and longest – then your policies are unjust, and you will not be addressing climate change in a just, fair and equitable manner.

So we said the climate-change science is solid. We have no problem with that. But the policy is where the justice part comes in. How do you address the issue of responsibility and vulnerability so that when you talk about adaptation and mitigation you don’t leave some folks on the other side of the levee, still being drowned? Or you don’t come up with policies that are not equitable, so that people can afford the kinds of interventions and retrofits and so on that will go across the board, and it’s not just left to market forces and who’s got money to leave and who’s got money to buy on the high ground or who’s got money to do whatever? That’s where we say that justice has to be integrated into the climate-change policies.

In order for that to happen, environmental justice and climate justice folks have to be in the room and have to have resources to speak for themselves and speak with authority in terms of what their issues are and what their priorities are. Even with our allies who were doing climate work, who came out of the environmental and conservation movement, we had to fight to deal with racial justice and equity. A lot of them took that same bias to the climate table, and we’re still getting them to understand what it is when we talk about climate justice.

Climate justice means climate change is happening right now in a lot of communities, and those communities that are getting hit the hardest are communities whose carbon footprint is the smallest. When we talk about those policies, we talk about things that can be done right now to address those marginalized communities and frontline communities. That’s the justice part that we’re talking about.

As we transition to renewables and clean energy, we also had to work with the environmental groups to talk about how as they started closing these dirty coal plants and got a lot of them closed, that the last remaining coal plants and the hardest to somehow get shut down or get converted to natural gas are the ones where people of color live.

And so we say, well, we can’t leave any communities behind. We have to make sure that we don’t leave the lead in the houses, just because we got lead out of the gasoline. The people who live with lead in the housing, we know who they are. They are poor people and people of color. And the same thing is true when we talk about this just transition in terms of moving to that green economy. We’re saying let’s make sure that we color-coordinate it in a way that we don’t leave people of color behind.

Now that makes perfect sense to those of us who have been working on justice issues for many years. But to some extent, some people who are working on climate issues said, well, if you bring all these social issues into it we won’t be able to get policy. Those of us who work on justice, we say you’re damn right. Because we’re not going to go for any policies and plans that somehow continue to marginalize us and leave us behind, and leave the dirty stuff in our communities.

Or come up with plans with pollution trading and all that kind of stuff that will trade our health and push those dirty industries to continue to come to our communities while more affluent places can get tax credits for what’s going on over there, over there, and over there. And this stuff keeps going to our communities. Our communities of color are more sophisticated today than they were 20 years ago. And we have more resources at our disposal in terms of experts who come from those communities. Community-based organizations have expertise. They have been able to push back on a lot of those plans that would somehow leave our communities out of the mix.

+++++

Bill Dawson is the founding editor of Texas Climate News.