Forecast issued Tuesday, June 18

By Bill Dawson

Texas Climate News

Hot, humid Houston’s tourism boosters do their best to put a positive spin on the weather. Local government’s official Visit Houston website, for instance, boasts that residents and visitors enjoy “an enviable outdoor lifestyle” and “temperatures rarely reach 100 F.”

City boosters aren’t paid to accentuate the negative, so it’s understandable that the website doesn’t mention one memorable feature of summer in the Bayou City — the exceptionally muggy nighttime conditions, when humidity levels soar and temperatures almost never fall below the 70s.

Well, welcome to the future, Houston. Increasingly, overnight lows are staying in the upper 70s and even the low 80s. This week’s weather forecasts, for example, called for several extremely sultry nights with low temperatures in the 80s.

In its rising minimum nighttime temperatures, or “high lows,” as they’re often called, Houston is just one example of a notable – and health experts say potentially dangerous – feature of a planetary climate that’s heating up in general, with overnight lows going up much faster than daytime high readings.

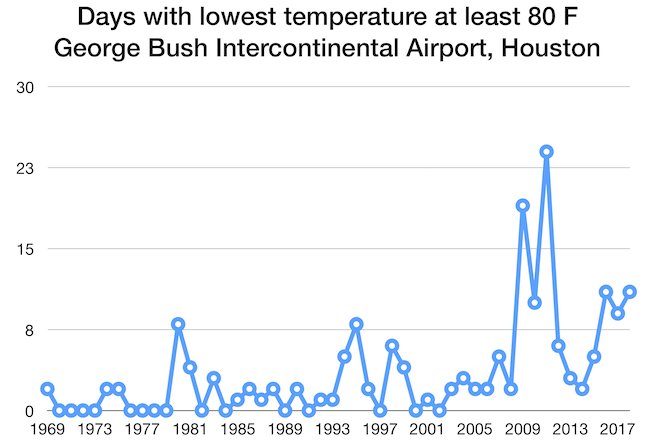

“High lows are increasing in frequency in the Houston area,” Texas State Climatologist John Nielsen-Gammon told TCN.

He said this trend is discernible in decades of temperature data for three Houston weather stations (downtown and at the city’s two major commercial airports) and one in Galveston, the Gulf Coast island city 45 miles from downtown Houston.

“Part of [the greater frequency of high lows] is the increase in sea surface temperatures and dew point temperatures, as seen in the Galveston data,” Nielsen-Gammon said.

“Another part of that is the urban heat island effect, which can be seen in the three Houston stations as the frequency of high lows increases at each station at a faster rate than at Galveston.”

Data: John Nielsen-Gammon

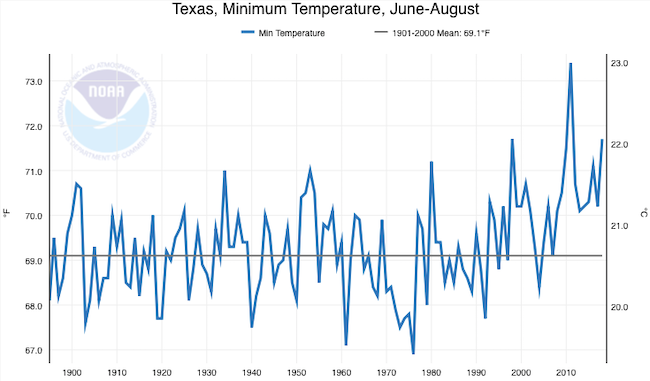

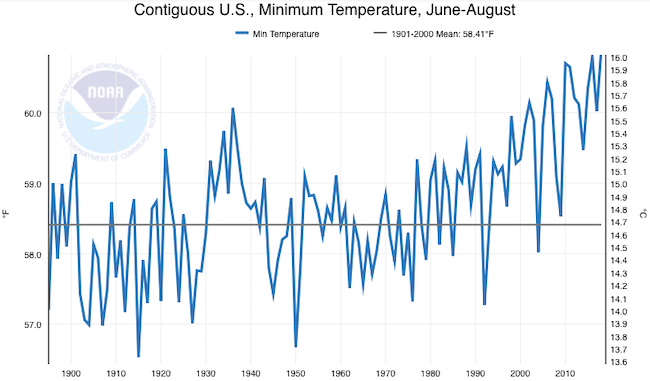

Statistics maintained by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration show upward trends for minimum temperatures during “meteorological summer” (June through August) in Texas and the contiguous U.S., as shown in these graphics charting readings from the late 1880s through 2018.

NOAA graphic

NOAA graphic

In its August 2018 National Climate Report, NOAA noted that the average nighttime temperature for the contiguous 48 states had reached a new record high level in the just-ended meteorological summer:

The nationally averaged minimum temperature (overnight lows) was exceptionally warm during summer at 60.9 F, 2.5 F above average and 0.1 F warmer than the previous record set in 2016. Every state had an above-average summer minimum temperature with five states record warm. In general, since records began in 1895, summer overnight low temperatures are warming at a rate nearly twice as fast as afternoon high temperatures for the U.S., and the 10 warmest summer minimum temperatures have all occurred since 2002.

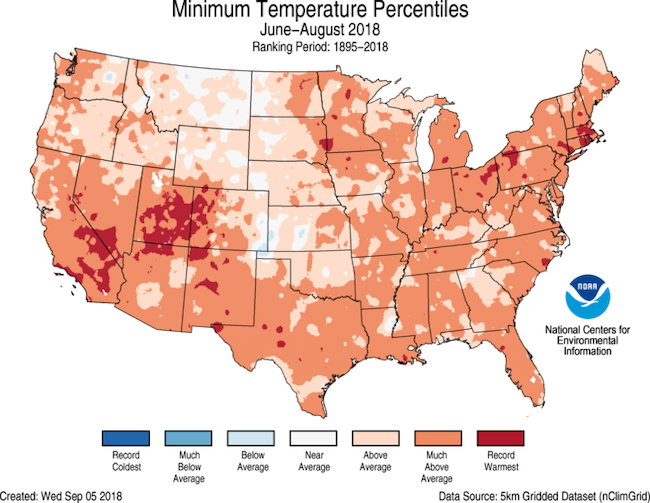

Summertime low temperature averages across almost all of Texas were in NOAA’s “much above average” category last year:

NOAA map

The various health risks that researchers are linking to higher nighttime temperatures in summer are, of course, greatly mitigated by air conditioning, which is widely used in residences at all economic levels in Houston and other Texas cities.

“A hundred and five degrees in San Francisco is going to have a bigger impact probably than 105 degrees in Houston, where everybody has air conditioning and people are accustomed to dealing with high temperatures,” Lara Cushing, a professor of environmental epidemiology at San Francisco State University, told the New York Times last summer.

Cushing elaborated on the potential health impacts of rising nighttime temperatures in a subsequent article published by the California State University System’s news office.

“From studying extreme heat events, we know that health effects are worse if heat persists overnight,” says Dr. Cushing. The body tries to maintain a relatively constant temperature within a range, and being exposed to heat for prolonged periods makes that difficult.

She explains that continued days of high temperatures can cause heat stress, heat exhaustion and heat stroke. “Cool temperatures at night give the body a little respite,” she says.

Without that break, people suffer. “We worry about night temperatures during heat waves because we see a rise in deaths as well as hospital admissions for types of conditions sensitive to heat,” she says. “Anyone healthy or sick can be vulnerable to heat stress during an extreme heat event. People with certain preexisting illnesses such as a heart condition or kidney issues are even more vulnerable. And the elderly who live alone and pregnant women are vulnerable – their thermoregulatory systems are often not as able to cool the body.”

Especially in places without widespread air conditioning, rising nighttime temperatures pose a growing challenge for public health officials mindful of incidents such as Chicago’s deadly heat wave nearly a quarter-century ago, as Time reported in 2016:

High nighttime temperatures have already been linked to hundreds of deaths, scientists say. They are part of what led to the particularly high death toll in the 1995 Chicago heat wave that killed more than 700 people. Researchers, including [NOAA senior scientist Ken] Kunkel, have documented how the city’s residents’ reluctance to open windows and turn on air conditioning at night drove the heat-related deaths.

In a study published in 2017, researchers at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine laid out their findings about statistical links in London between higher overnight temperatures and mortality. They wrote:

Exposure to high daytime temperatures is known to increase the risk of death in vulnerable individuals. This study shows that high nighttime temperatures carry an additional risk of heat-related death, which may be highest in patients with heart diseases, particularly those most likely to suffer from stroke and chronic ischemic diseases. In addition, nighttime temperatures make an important contribution to mortality risk in people below the age of 65 years. The study also demonstrated that warm nights preceded by a hot day have the greatest health impacts, indicating that nighttime temperatures are an important consideration when developing heat-health warning systems.

A faster increase in nighttime temperatures has been observed around the world and is likely to continue for decades, researchers at Norway’s Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research wrote in a 2016 study published in the International Journal of Climatology.

The authors analyzed causes of the more rapid temperature rise at night. They concluded that in addition to previously noted factors including increases in cloud cover, precipitation and soil moisture, nighttime atmospheric conditions are inherently more sensitive to man-made emissions of greenhouse pollutants.

A Bjerknes Centre article about the study explained this finding:

The layer of air just above the ground is known as the boundary layer, and it is essentially separated from the rest of the atmosphere. At night this layer is very thin, just a few hundred meters, whereas during the day it grows up to a few kilometers. It is this cycle in the boundary-layer depth which makes the nighttime temperatures more sensitive to warming than the day.

The build-up of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere from human emissions reduces the amount of radiation released into space, which increases both the nighttime and daytime temperatures. However, because at night there is a much smaller volume of air that gets warmed, the extra energy added to the climate system from carbon dioxide leads to a greater warming at night than during the day.

This higher sensitivity of night-time temperatures has also affected the number of cold-extreme nights we have seen in recent years. The number of extremely cold nights has dropped by half during the last fifty years, in contrast to the extreme-cold days which have decreased by a quarter.

+++++

Bill Dawson is the founding editor of Texas Climate News. John Nielsen-Gammon is a member of TCN’s volunteer Advisory Board, serving solely in his capacity as regents professor of atmospheric sciences at Texas A&M University.