By Ruth SoRelle

By Ruth SoRelle

Texas Climate News

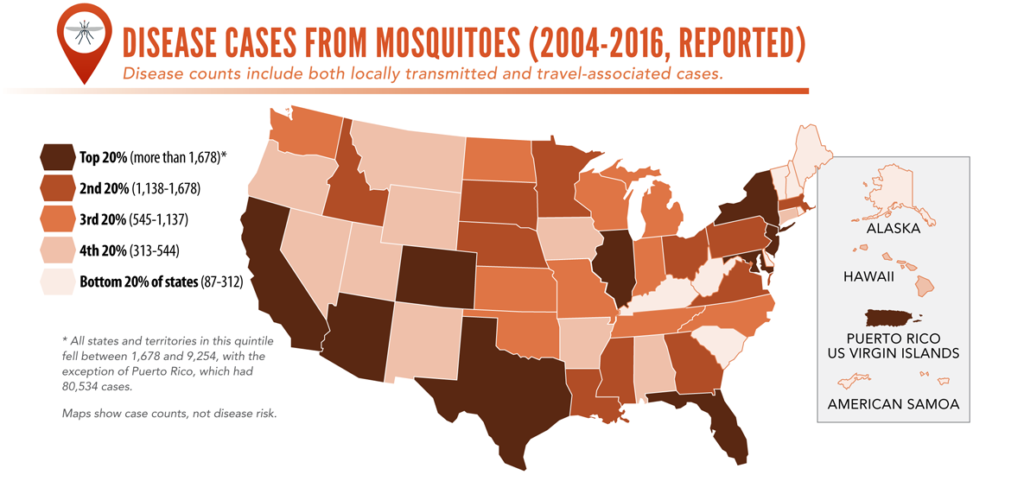

The number of disease cases resulting from mosquito, tick, and flea bites nationally tripled to 642,602 between 2004 and 2016, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s division of vector-borne diseases announced last month.

Vectors are organisms, usually insects or ticks, that transmit a disease or parasite.

The discovery that vector-carried diseases are exploding in no way surprised Dr. Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. What’s more, Texas is a special case, he told Texas Climate News.

“While there’s the threat of climate change in the whole United States, Texas is at disproportionate risk from global warming,” he said.

“By some estimates, Texas is projected to reach 80 to 100 days of temperatures over 95 degrees Fahrenheit by 2050, compared to 40 such days over the last 30 years. The state will face rising sea levels and other negative effects [of climate change]. Of particular relevance and concern are the warming effects conducive to insect vector expansion and transmission – mosquitoes, sandflies and kissing bugs.”

If you look at tick distributions – the Lone Star tick (diseases carried: ehrlichiosis, southern tick-associated rash illness, tularemia and Heartland virus), blacklegged tick (Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, babesiosis, Borellia infections) and the dog tick (Rocky Mountain spotted fever and tularemia), a feature of all three is that they meet in East Texas, Hotez said.

Mosquito-borne diseases, including West Nile, dengue fever, chikungunya and the recently recognized Zika, all threaten to be major problems in the United States and pose a special threat to Texas and Houston, he said.

The top mosquito-borne disease in Texas in 2016 was West Nile virus (906 mosquito-borne cases). The top tick-borne disease was spotted fever rickettsiosis (179 cases). Chaga’s disease, transmitted by triatomine or “kissing” bugs, has been identified in immigrants from Central and South America. It is considered one of the neglected parasitic infections. Fleas can carry Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that causes plague. Occasional infections occur in the western part of the United States and Texas as well as Africa and Asia.

Unlike some CDC officials’ apparent reluctance, Hotez is not afraid to use the term “climate change” in connection with these diseases.

“We are at the epicenter of vector-borne diseases in the United States, he said. “I consider Texas part of a ‘hot zone’ globally, and the question is why?”

Clearly, poverty is a risk factor, where inadequate housing and malnutrition along with lack of air conditioning can leave residents subject to insect-borne diseases. Texas’ population boom means many of the people coming into the state are seeking homes in the city’s urban areas. Texas has the five fastest-growing small cities and five of the eight fastest-growing large cities in the nation, Hotez said.

Human migration itself plays a role in the spread of such diseases around the world. Other contributing factors include declining rates of vaccinations, trans-border traffic and sea transportation that has grown significantly since the doubling of the capacity of the Panama Canal.

“We have the perfect storm in Texas,” Hotez said.

However, teasing out the contribution of each factor is difficult, requiring the expertise of more than biomedical scientists. A virus expert writes grants and papers for other virologists. Microbiologists write for other microbiologists.

“They certainly don’t talk to an economist or a political scientist or anthropologists or those who study climate change,” Hotez said

In a landmark study published in 2013 in the journal Vector Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, Kristy O. Murray, a professor of pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine, showed evidence that there were unrecognized outbreaks of dengue fever in Houston in 2003, 2004, and 2005.

“We are not set up to do what’s called active surveillance,” Hotez said, adding that no state has such a program. “We don’t have the funding to go into a community you might think would be at risk of something like dengue or Zika and follow the community members, take their blood and look for when the epidemic appears. In Texas, Harris County is an exception with a mosquito control authority that collects mosquitoes and tests them for viruses.”

Lyle Peterson, director of the CDC’s division of vector-borne diseases, in his press conference announcing the disease-case rise last month acknowledged that funding and support is lacking. In its report, the CDC noted that approximately 80 percent of vector control organizations in the United States lack critical capacity to prevent and control the spread of vector-borne diseases.

Considering the major flooding events that have hit the Houston area over the past three years – the Memorial Day Flood in 2015, the Tax Day Flood in 2016 and Hurricane Harvey in 2017 – the question arises: How will such events affect vector-borne diseases in the future?

“As you know, the floodwaters initially wash away mosquito-breeding sites, but that short-term benefit ebbs when the floodwaters recede, leaving the puddles in which the insects breed,” Hotez said.

Climate change itself encourages such breeding, increasing the breeding season for the pesky insects.

“You can’t say climate change isn’t real,” Hotez said. However, defining the extent to which it contributes to vector-borne disease may be almost impossible. That said, the factors that lead to such diseases will continue.

“All the factors I’ve listed such as migration and urbanization are not going to go away. Poverty isn’t going away either. The anti-science movement seems set on blocking interventions that fight these diseases.”

While Hotez is not loath to use the term “climate change,” the leaders of the CDC evidently are. When directly asked during the CDC press briefing about the contribution of climate change to vector-borne diseases, Peterson hedged.

“What I can say is that any of these diseases are very sensitive to temperature. And when there are increasing temperatures, it promotes several things….Temperatures tend to make mosquitoes more infectious and infectious faster, thus promoting outbreaks.”

+++++

Ruth SoRelle, a TCN contributing editor, is a veteran medical and science writer based in Houston. She holds a master’s degree in public health from the UTHealth School of Public Health in Houston.