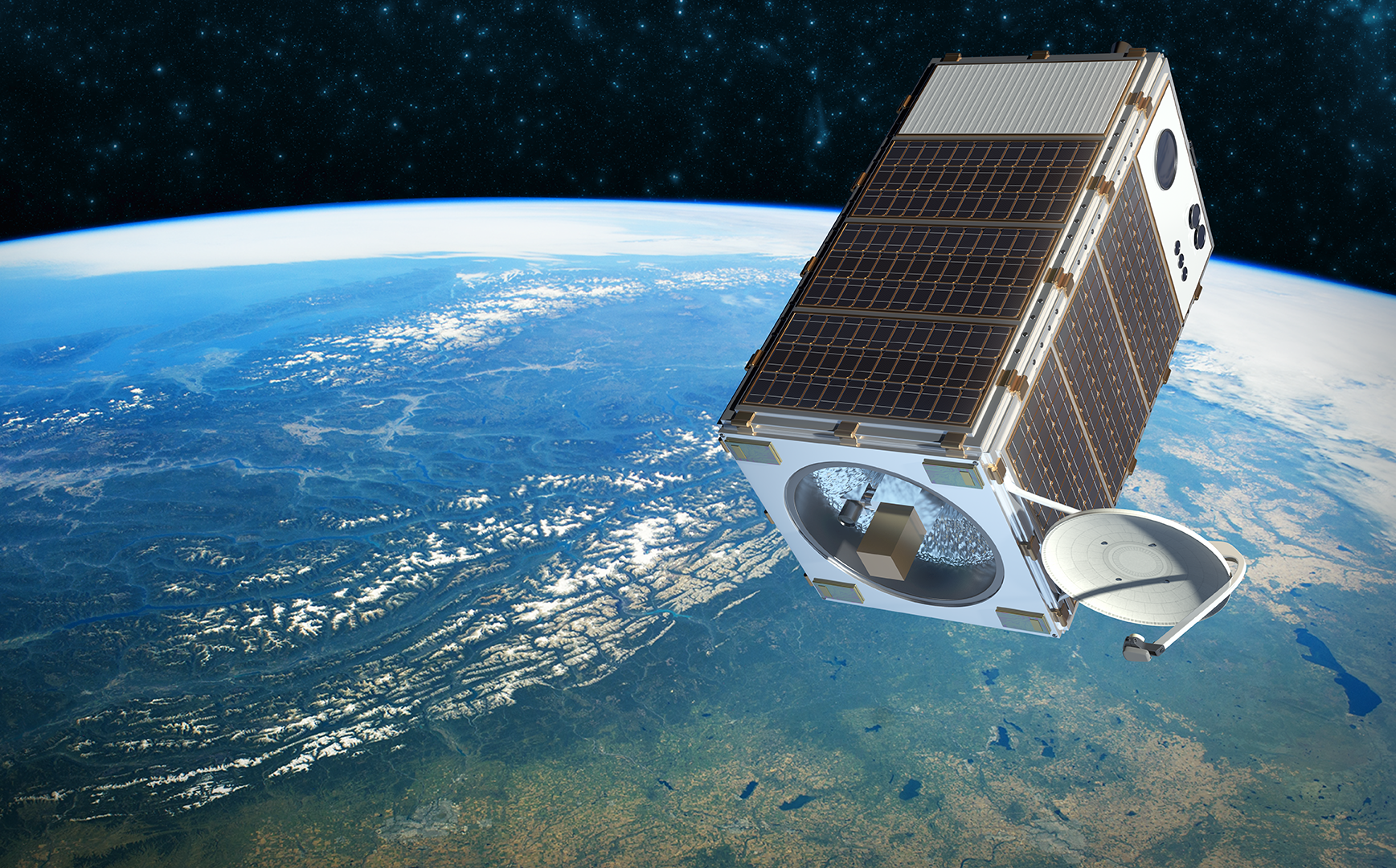

An artist’s conception of what the Environmental Defense Fund’s methane-sensing satellite may look like in orbit.

By Joseph A. Davis

Texas Climate News

WASHINGTON – Climate-disrupting methane, also known as natural gas, is still politically explosive as legal and regulatory struggles continue under the Trump administration. It is something Texas cares about, especially with the oil and gas production booming yet again in the western part of the state.

Because methane looms so large in its atmosphere-warming capability, environmentalists plan to launch a satellite to measure methane plumes, which are a kind of “smoking gun” showing emissions by oil, gas, landfill, feedlot, and other industrial operations. The Environmental Defense Fund announced its plan April 11, although it is still raising money for the project.

EDF says the satellite, initially targeting methane from oil and gas operations, would help identify hot spots for emissions, aiding companies and governments in efforts to reduce them.

“Cutting methane emissions from the global oil and gas industry is the single fastest thing we can do to help put the brakes on climate change right now, even as we continue to attack the carbon dioxide emissions most people are more familiar with,” said Fred Krupp, the organization’s president.

The Trump administration is unpersuaded, however, by such arguments about the urgency of methane emission cuts from oil and gas operations. Two big federal rules to limit methane emissions are currently under contention – both laid down during the Obama administration and both put on hold during the Trump era. One, issued by the Bureau of Land Management, would govern methane emissions from drilling operations on federal lands. The other, actually a set of rules, by the Environmental Protection Agency, covers oil and gas wells across the U.S.

Both of these rules were proposed fairly late in the Obama administration. Both were opposed by much of the oil and gas industry. Both were put on hold, or delayed, by the incoming Trump administration. Both have ended up in court, with the industry resisting them and environmental groups pushing them. None of those court cases (or the further rulemakings they may lead to) have reached a final resolution.

Why regulate methane – something petroleum-producing operations often flare off as a nuisance? First, it’s a powerful greenhouse gas that worsens climate change. Second, it’s worth money (in royalties) to the federal Treasury. Third, it’s worth money (in sales and profits) to oil and gas companies. And once in a rare while, it blows something or someone up.

Methane is scarcely profitable when it is far away from gas-collection pipeline networks, which could get it to market. Natural gas prices have fallen dramatically in the last decade as domestic production from shale formations using fracking technology has surged. In fact, because U.S. gas production is near a historic high, prices are likely to stay near where they are now – low. That lowers producers’ incentives to get economically marginal methane to market.

But gas prices in a complex market depend on lots of factors, key among them being where the gas is located. Today, the U.S. looks to become a significant exporter (by shipping it as liquefied natural gas) to regions of the world even hungrier for it than the United States is. So pipelines and terminals matter. Also, to be commercially useful, gas must often be processed to purify it.

When drillers bring up crude oil, it often includes some gas. This is why you often see gas being flared from remote – or not-so-remote – petroleum production facilities. What you will not see (unless you have the special instruments environmentalists want to launch aloft) is the large amount of gas that leaks unnoticed from leaky fittings (“fugitive” emissions) or is being deliberately vented.

EPA Methane Rule

EPA originally published its rule to control methane emissions from oil and gas facilities in June 2016. Once Scott Pruitt came in as administrator (and President Trump signed an executive order), EPA moved in April 2017 to stay and delay the rule’s effect. Then the whole argument went to court.

The case tests the legality of a key Trump administration tactic – delaying a rule’s effect rather than repealing or replacing it outright. To repeal or replace a rule takes another rulemaking, a time-consuming process with an uncertain outcome. Under Pruitt and other Trump agency heads, this administration seized on the delay gambit as an expedient. But it has not held up well in court.

In July 2017, nine of the 11 judges on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ruled that the delay tactic was unlawful and that EPA would have to enforce the Obama methane rule while it went through a new rulemaking. Many Republicans side with the oil industry in opposing the rule. The House even voted in September 2017 (mostly on party lines) to block funds to carry it out. Since then, EPA has tried another gambit by amending the rule. Since then, 14 states led by New York have this month gone to court pushing to enforce the Obama EPA methane rule.

While the American Petroleum Institute opposes the Obama rule, the industry is not monolithic. In fact, API says, the industry is reducing emissions on its own. And this is true – to some extent. There has grown up a significant sub-industry devoted to detecting and reducing methane emissions from oil and gas facilities. ExxonMobil, the nation’s biggest natural gas producer, announced its own program to reduce methane emissions in September 2017.

The Environmental Defense Fund reported this month, however, that an analysis it had conducted suggests “just six companies that represent only three percent of global oil and gas production currently report quantitative methane emission targets.”

EDF’s white paper argued that targeted commitments from more companies to cut methane emissions from both gas and oil operations will represent “a tangible step by industry to slow the rate of warming now and can help companies mitigate regulatory risk.”

Unlike many other environmentalists, EDF argues that climate-protecting benefits of natural gas, as a cleaner-during alternative to coal to produce electricity, can be realized if methane emissions are greatly reduced.

Meanwhile, the process of completely overhauling the EPA methane rule still inches ahead.

BLM Methane Rule

The Bureau of Land Management rule applies only to wells drilled on leased federal lands (most of which are managed by BLM). Since the federal government sets the terms of the lease, it has more leverage. The rule requires well operators to minimize flaring, venting, and leaks from these wells. BLM proposed it in January 2016.

Since the Obama rule was not finalized until November 15, 2016, it was subject to congressional reversal under the Congressional Review Act, which GOPers used to kill many other late-breaking Obama rules. It came as a surprise, then, when the Senate rejected reversal of the BLM rule by a narrow 51-49 vote in May 2017.

That did not end the fight. By December 2017, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke (the boss of BLM) had announced that he would delay the rule’s effect for a year. That prompted litigation, and a federal judge in February 2018 ruled the Zinke BLM could not delay the Obama rule.

By February 12, 2018, BLM had proposed revising the rule itself (or, some said, gutting it). By February 22, a judge ruled that BLM had to enforce the Obama rule in the meantime. Then on April 5, another judge ruled that BLM did not need to enforce the Obama rule while it is working on a new one.

Yes, the on-again-off-again saga is dizzying; but as of this moment, the Obama BLM methane rule is off again. Stay tuned.

+++++

Joseph A. Davis, Washington correspondent for Texas Climate News, is a veteran journalist covering energy and the environment.