Debris litters a beach on Mustang Island, an 18-mile barrier island stretching from Corpus Christi to Port Aransas.

By Neil Strassman

Texas Climate News

SAN DIEGO – The Texas coast is littered with about ten times more plastic debris than the beaches of the eastern Gulf of Mexico.

In fact, Texas has more marine debris along its waterfront than any other state in the nation, say oceanographic researchers and conservationists.

The stark news about the Texas coast was delivered in two discussions of ongoing, unpublished research presented at the Sixth International Marine Debris Conference in San Diego this week.

It’s not driftwood, folks.

It’s plastic.

And there’s an astonishing amount of it: An estimated two billion pieces of plastic call the nation’s coastline home and Texas gets more than its fair share.

Everything from bottles, cups and straws to plastic rope, jugs, crates, nets and fishing line. There are candy wrappers, plastic bags and cigarette butts, hard and soft plastic – and don’t forget the bottle caps.

Need a toothbrush? Go to the beach.

In the heat and the ultraviolet light the plastic degrades and breaks apart, getting smaller and smaller, uncollectible, until the white sandy beach becomes the white plastic sandy beach.

The smaller the particle, the easier it is to be eaten by seabirds and to work into the aquatic food chain.

The debris damages wildlife, fisheries, tourism, poisons the aquatic environment and destroys the natural beauty of the Texas coast.

Expect more plastic debris, not less

The problem is getting worse, not better, said George Leonard, chief scientist for the nonprofit Ocean Conservancy.

Eight million metric tons of plastic worldwide flows into the ocean every year and another 350 million metric tons is produced annually, Leonard said.

“All signals point to more plastic, not less,” he said. “How do we bend that trajectory so we don’t kill the ocean.”

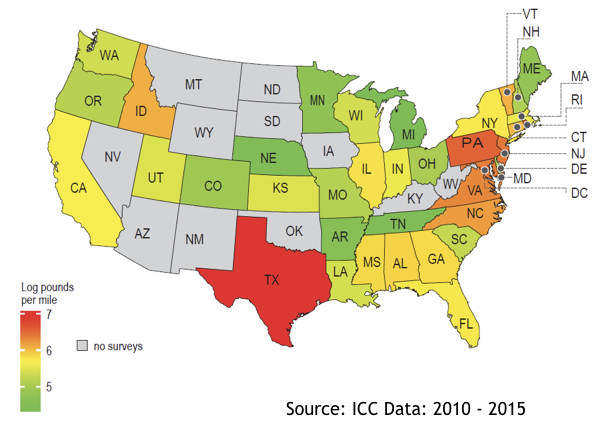

A study presented at the San Diego conference found that Texas leads the nation in marine debris.

In 2015, the Conservancy joined with the federal National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to identify geographic patterns and trends in marine debris distribution and to improve monitoring and cleanup.

The Conservancy had organized and collected data on beach cleanups for 30 years, which was used for the study. NOAA’s Marine Debris Monitoring Program had cleanup data for five years.

They enlisted the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization of Australia to crunch the data for the U.S. coasts.

It took a year, said Chris Wilcox, a quantitative ecologist and the Australian organization’s chief scientist.

“It’s the first time anyone had a go at a statistical analysis of the data that’s been collected,” he said.

[See “Worldwide, plastic debris inspires action” below this article]

The study showed that marine debris in the U.S. is largely homegrown. It comes from urban areas and tends to collect nearby, though it is highly variable and can, at times, end up in other places, Wilcox said.

“Effectively, people here are dumping into the ocean,” Wilcox said. “We must get better at waste management to compensate for the increase in plastic production, which doubles every 11 years.”

Between now and 2029, he said, the world will make as much plastic as it has made from the advent of the commercial plastics industry in the mid-20th century until now.

The study also showed that Texas currently leads the nation in marine debris.

Gulf currents do a job on Texas beaches

There is precedent for debris to collect in the area around the Coastal Bend of the middle Texas coast, said Larry McKinney, executive director of the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies, a part of Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi.

“There is a series of currents in the eastern Gulf that deposit the debris in Texas. “It’s been that way for hundreds of thousands of years.”

The currents in the Gulf are finicky.

Even the great Loop Current that flows north into the Gulf between Cuba and the Yucatan Peninsula is subject to strange machinations.

A plastic bag adorns a Carolina wolfberry bush, a favorite food of whooping cranes. Members of the highly endangered bird species spend winters on the central Texas coast.

It usually heads for the nation’s southern coastline, swings to the east and then tracks south along Florida to exit in the Atlantic. Every once in a while large eddies – rings of current that can measure 200 miles across and last for a year – spin off the Loop and head for the Texas coast or Mexico.

The bottom line: The 367-mile Texas coastline may only rank as the sixth longest among all the states, but Lone Star beaches get hammered.

NOAA researchers Katie Swanson in Texas and Caitlin Wessel in Alabama have found that with the exception of summer, currents push their bounty to the west and into Texas. In the summer, currents push northward across the Gulf onto the state’s beaches.

“There’s a lot of debris and 90 percent is plastic,” said Swanson, stewardship coordinator for the Mission-Aransas National Estuarine Research Reserve, an area close to the center of the Texas coast.

Swanson studied debris on some of Texas’ barrier islands, including the uninhabited and privately owned San Jose Island, and found that there was as much debris there as in other places with public access.

“There’s 10 times more trash than on the Texas beaches than in Alabama and the eastern Gulf,” she said.

McKinney, who previously served as director of coastal fisheries and aquatic resources for the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, acknowledged that the burden of marine debris that Texas bears is heavy.

“Some of it we just do to ourselves, and some of it just gets done to us,” he said.

Worldwide, plastic debris inspires action

Plastic debris on beaches and in oceans, plus other problems related to managing the world’s enormous volume of plastic waste, is prompting action in many locations.

California banned checkout-line distribution of free, single-use plastic bags at many stores in 2016. More than 40 nations including Kenya, China, the Netherlands, the U.K. and France have banned, restricted or taxed bags. Single-use straws, cups and bags are next on the chopping block.

Seagoing nations are enlisting commercial fishermen to protect and retrieve their gear to reduce abandoned traps, fishing line and nylon rope in the ocean.

Efforts are underway to decrease plastic packaging and reduce the ubiquitous polystyrene foam containers for food and other items that are widely used in developing countries. Reusable containers are gaining traction.

Industry and conservationists are exploring an alliance in a number of waste-management arenas to mold effective policies to create value and drive behavioral change. – Neil Strassman

+++++

Neil Strassman, an independent journalist in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, is a Texas Climate News contributing editor. Among his past positions in newspaper journalism, broadcasting and local government, he worked for 20 years as an environment, science and political reporter at the Long Beach (California) Press-Telegram and Fort Worth Star-Telegram.