This article is part of an occasional TCN series on health issues related to climate change.

+++

By Bill Dawson

Texas Climate News

There’s been a burst of worrisome news about the mosquito-borne Zika virus in recent days.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned on Monday that pregnant women should avoid visiting part of the Miami area where 14 people contracted Zika, which can cause severe birth defects. State health officials said the infected individuals probably caught the disease locally.

The CDC said last week that Zika could affect as many as 10,000 pregnant women in Puerto Rico this year. The New York Times reported that the Zika epidemic that began in South American is “raging in Puerto Rico — and the island’s response is in chaos.”

Amid these and other recent Zika developments, Climate Central, a nonprofit research and reporting organization, released a report concluding that the warming climate, bringing higher humidity with higher temperatures in many places, has lengthened the mosquito-breeding season across most of the contiguous 48 states.

“The overall increase in mosquito days in the [contiguous] U.S. is likely increasing the risk of several mosquito-borne diseases, including the Zika virus,” the researchers concluded.

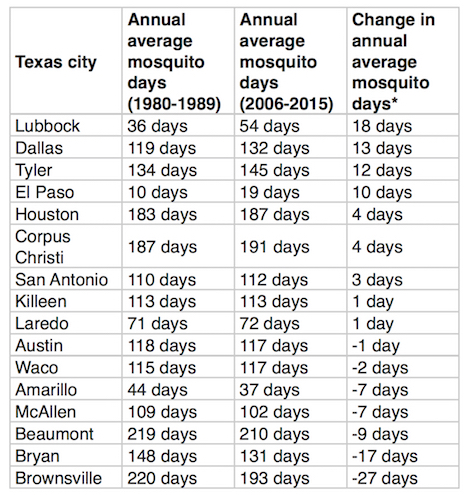

The Climate Central report examined data from the largest 198 U.S. cities, comparing their average annual days with “ideal” climate conditions for Asian tiger mosquitoes, one of the types that carries Zika, in the 1980-1989 period and in 2006-2015.

“We found that in most of the country, rising temperatures and humidity since the 1980s have driven an increase in the number of days each year with ideal conditions for mosquitoes,” the researchers said. “Warming temperatures lead to more evaporation, which puts more water vapor in the atmosphere and increases humidity.”

Texas Climate News analyzed the Climate Central report, finding a mixed picture in terms of changes in mosquito-breeding days across Texas.

Of the 16 Texas cities in the report, nine had longer average mosquito seasons in 2006-2015, ranging from Lubbock’s 18-day increase to seasons that were a day (or part of a day) longer in Killeen and Laredo. Seven cities had fewer mosquito days, on average in the 2006-2015 period, ranging from a one-day-shorter breeding season in Austin to Brownsville’s 27-day decline in the number of breeding-conducive days.

The drop in Brownsville’s average annual number of mosquito days was the largest in the nation. But the city, situated at the southernmost tip of Texas, still had 193 annual mosquito days on average from 2006-2015, the 23rd-longest mosquito season among the 198 cities that were studied.

[Related coverage: Climate change and globalization driving tropical diseases toward Texas]

Beaumont’s mosquito season dropped from an annual average 219 days in 1980-1989 to an average 210 days in 2010-2015. It had the 17th-longest season among the 198 cities in the latter period.

Twelve of the 16 Texas cities that were studied had mosquito seasons in 2006-2015 that were 102 days or longer.

Climate Central’s definition of ideal mosquito-breeding weather for the study was days with a temperature between 50-95 degrees Fahrenheit and relative humidity greater than 42 percent.

The researchers addressed the phenomenon of fewer mosquito days in some locations, focusing on their Texas findings:

[In addition to longer mosquito seasons in many cities,] we also discovered that in a few locations, temperatures have increased so much since the 1980s that the overall mosquito season has decreased slightly. For example, five Texas cities (all of which have seen large increases in extreme heat over that time) have seen their mosquito season decrease by 5-30 days. However, four of these cities [McAllen, Beaumont, Bryan and Brownsville] are still seeing an average of at least 100 days each year with ideal conditions for mosquitoes, so the overall threat has not decreased considerably.

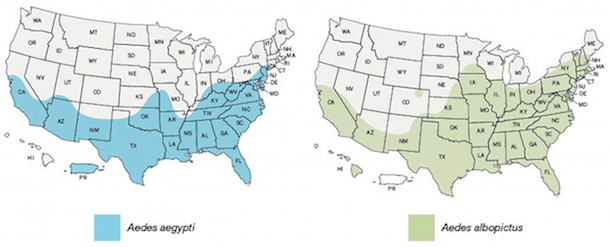

CDC’s estimated range of Zika-carrying mosquitoes

Two types of mosquitoes can carry and transmit the Zika virus – Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, also called Asian tiger mosquitoes, which was the only kind assessed in the Climate Central analysis. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are more likely to spread Zika, dengue, chikungunya and other viruses to people. These two maps show the CDC’s “best estimate of the potential range” of the two Zika-transmitting mosquito types, including “areas where mosquitoes are or have been previously found.” CDC cautioned that the maps “are not meant to represent risk for spread of disease,” and don’t show the likelihood of mosquitoes spreading Zika or other viruses, numbers of mosquitoes in certain places, or mosquitoes exact locations. To date, health officials have identified Miami as the only place in the contiguous United States where they believe Zika cases have been acquired so far from local mosquitoes. [http://www.cdc.gov/zika/vector/range.html]

Florida faces the most troubling situation regarding potential increases in mosquito-borne illnesses, Climate Central concluded:

Florida cities face the greatest overall threat from mosquitoes; most of its major cities face hundreds of days each year with climate conditions that are ideal for these insects. Many of these cities have seen an overall increase in mosquito days since the 1980s, but a few cities, like Fort Myers and Orlando have slightly shorter seasons now than they did 35 years ago.

Image credits: Photo – Harris County Mosquito Control District; Chart – Texas Climate News (based on Climate Central data); Maps – U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

+++++

Bill Dawson is the founder and editor of Texas Climate News.