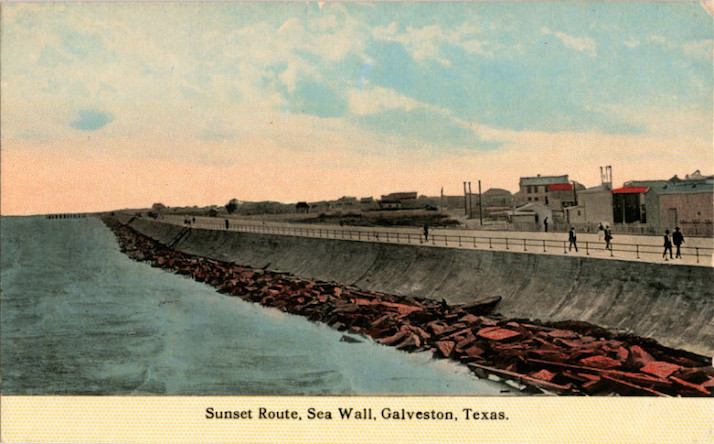

Galveston’s famous seawall was pictured on a 1907 postcard, soon after it was built. The seawall was constructed after a 1900 hurricane killed an estimated 10,000-12,000 people in the city of Galveston and elsewhere on Galveston Island and destroyed much of the city.

By Jan Ellen Spiegel

Yale Climate Connections

In the years since Katrina decimated the Gulf Coast and Irene and Sandy inundated just about everything from the Caribbean to Canada, there’s been ongoing second-guessing on what should have been done to better protect those coastal areas.

Once, the instant answer would have been a seawall. Or maybe a bulkhead, revetment, groin, jetty. Something hard to hold back the water.

According to research released in 2015 by Rachel Gittman, a post-doctoral researcher at Northeastern University’s Marine Science Center, about 14 percent of the U.S. tidal shoreline has been hardened.

But many now believe that softer shoreline defenses are better.

Such defenses allow water and the land next to it to do what they naturally do to protect themselves in the face of storms, sea level rise, and erosion.

Living shorelines are the current darling of the soft concept. They are typically sloping barriers that mimic natural shorelines. They are planted with vegetation and salt marsh to help make them strong. They buffer, but they also move and change as any undeveloped shoreline would.

But all shoreline protections have benefits and pitfalls that need to be weighed against each other.

How well do soft and hard methods protect the shoreline?

“It truly depends on what you’re trying to protect,” said Kimberly Penn, climate coordinator for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Office for Coastal Management, which now encourages living shorelines.

Seawalls and their smaller cousins, bulkheads, can keep water out, the same way any high, thick, sturdy wall would.

But only if it’s your high, thick, sturdy wall.

A neighbor without hard protection will generally suffer increased damage from waves deflected by an adjacent property with a wall.

“They so dramatically alter what’s going on next door that erosion rates seem to just skyrocket,” said Steven Scyphers, another researcher with Northeastern’s Marine Science Center.

The land behind a wall isn’t totally safe either. A hard structure actually amplifies the force of the waves that hit it. Add in the extra water from sea level rise, and the dynamic gets worse.

The result is scouring. That’s when waves hitting a wall have nowhere to go, so they go down, digging out whatever’s below the wall. If waves go over the top of the wall, they’re likely to scour out the other side, too.

Bottom line: The wall will eventually collapse.

Water action against a wall will also cause any sand on the water side to wash away – so goodbye, beach. Cumulatively, the impacts mean loss of habitat for fish and animals, and because there’s less vegetation, decreased carbon storage capability. If a wall is blocking a salt marsh, it will prevent that marsh from doing what it’s supposed to do – soak up water during storms.

“The natural science is becoming increasingly clear that artificial structures just are not as ecologically beneficial as the natural,” Scyphers said. “But some are worse than others, and the bulkheads seem to be by far the worst.”

Living shorelines and vegetated dunes are designed to soften water impact by providing a slope the water can run up to dissipate its force. They leave habitat in place for animals and plants. Salt marshes stay in place to do their work. And as long as there’s no other blocking infrastructure, like a road, they let all of the above move and shift as needed.

But they really can’t handle the big stuff.

“They can mitigate wave impact, so they can help slow down chronic erosion or help reduce the wave impact during a storm to some degree. But they’re not going to save you from a 12-foot, 16-foot storm surge,” said Rob Young, director of the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines at Western Carolina University. “If there are areas that are critical to defend, then massive engineering is probably still the best way to do it. You’re not going to defend a coastal nuclear power plant with oyster bags and a salt marsh.”

What are the costs, financial and otherwise, to build and maintain shoreline protections?

Many believe the cheapest shoreline protection is a seawall or bulkhead, because neither needs the maintenance living shorelines or dune systems do.

Not so, according to research by Scyphers. “If you look at what they actually spend, the homeowners with the artificial shoreline spend twice as much money and invest twice as much time in maintaining their shorelines on an annual basis as those with natural shorelines,” he said.

And that’s just regular maintenance. Initial data on storm repairs seem to show the same trend, he said.

Rebuilding a wall that’s had a catastrophic collapse is likely to be far more expensive than replenishing a storm-damaged soft shoreline, which may not need to be fixed at all.

“A living shoreline could have a loss of marsh coverage in one year, but it can rebound on its own the next year,” Gittman said. “Just because a storm comes through and rips up some of your marsh, doesn’t mean it’s failed.”

But it takes a little fortitude to wait. “Some people are never going to be comfortable with that,” she said.

Why not use both?

Living shorelines and dunes need more space than sometimes is available or advisable. Walls, on the other hand, can be impractical for certain locations. So there’s a third option – both.

“Wherever feasible, incorporate living components,” Gittman said, echoing a growing sentiment. She and others recommend augmenting seawalls or bulkheads with offshore rock and rubble deposits, oyster or mussel reefs, and marshes.

“It’s not a true living shoreline,” she said. “But it’s better than just a seawall.”

That’s the thinking behind efforts along Alabama’s 600 miles of twisting shoreline, 40 percent of which is already hardened and 80 percent of which is privately owned.

The Alabama Nature Conservancy is promoting a stair-steps cage system – a series of cages that step down from a bulkhead. As seen in this series of photos, over time, marsh plants grow up through the cage slats, creating a slope that helps dissipate the wave action against the bulkhead.

“It’s a lot less intense and doesn’t travel down the shoreline like a bulkhead slap would,” said Judy Haner, director of the conservancy’s marine and freshwater program.

But Western Carolina’s Young has a warning for any shoreline protection: “They’re ‘BAND-AIDs.’”

“I’m very concerned about the fact that many state and federal agencies and many fine environmental organizations are spending all of their time still trying to hold shorelines in place,” he said. “Every living shoreline that’s trying to hold the shoreline in place comes with an expiration date. It may be 10 years from now. It may be 20 years from now. But with continuing rising sea levels, they’re going to be gone.”

So why isn’t everyone choosing soft shorelines?

Public policy in the U.S. makes it a lot easier to build hard shoreline protections than soft ones.

“In North Carolina right now, you can get a bulkhead permit in a couple of days, sometimes even the same day,” said Gittman, who conducts much of her research there. “The living shoreline takes a longer period of time, usually 30 days.”

The story is much the same at the federal level. Under the Clean Water Act, the Army Corps of Engineers has permitting jurisdiction over structures in the water, and that includes most shoreline protections. The Corps has a general permit offering streamlined approval for most hard structures.

But soft ones – living shorelines in particular – almost never qualify for the simpler general permit.

That could be changing. On June 1, the Corps unveiled a draft general permit for living shorelines that it hopes to have in effect by March 2017, Gittman and Scyphers said: They would also like to see national restrictions and disincentives for seawalls and bulkheads.

Among the states, only a handful have regulations that specifically encourage non-hard shoreline protection. Outright prohibitions of seawalls and their relatives are almost non-existent. And in most states, if you already have a seawall, you can rebuild it indefinitely.

+++

The case of the eroding Rhode Island beach road

Rhode Island could be exhibit “A” of why it’s so difficult to give up seawalls. Widely considered the most forward-thinking state for advancing softer shoreline protections, Rhode Island has been discouraging seawalls for years – though it outright prohibits them from only a small category of properties.

But even those policies were no match for the folks in the Matunuck section of South Kingstown, a coastal town 30 miles south of Providence. Matunuck Beach Road lies feet from the water, and waves eroding the sand threaten to collapse the road. It is the only access to nearly 250 homes.

After looking at the options, Rhode Island’s Coastal Resources Management Council chose the very thing it tries to discourage – a seawall, in this case made from layers of steel known as sheet pile and concrete.

“It was kind of like the least evil thing,” said Laura Dwyer, the Council’s public educator and information coordinator, who said the waves along Matunuck Beach are too ferocious for a living shoreline. “Aside from relocating the road and waterline underneath it, this was the only other option,” she said.

But that wasn’t the end of it.

Once the seawall was built, there would still be a number of properties left on the water side of it, including the Ocean Mist, a tavern sitting on stilts right at the water’s edge. Its owner waged a several-year battle claiming the wall would ultimately result in the loss of the Ocean Mist.

He was probably right, since seawalls typically cause the beach on the water side to wash away. “That is the evil of any sort of shoreline protection facility that you build,” Dwyer said. “Where it ends – you’ve got a problem. It’s going to exacerbate erosion.”

In the end, the Council green-lighted another hard structure to keep the Ocean Mist from washing away – at least in the near term. The Council is allowing the Ocean Mist to rebuild an old revetment – a somewhat porous stone wall just off the shoreline designed to lessen wave impact – to save the building from its almost assured destruction.

But in truth, it’s just a temporary fix. “We really need to look long-term and think about if we really should be living here,” Dwyer said. “The general public perception is that it’s going to protect things,” she said of a hard protection. “But it won’t.”

+++++

Yale Climate Connections, an initiative of the Yale Center for Environmental Communication, is a nonpartisan, multimedia service providing daily broadcast radio programming and original web-based reporting, commentary, and analysis on the issue of climate change.

Jan Ellen Spiegel is is a freelance writer and editor based in Connecticut. In 2013, she received a Knight Journalism Fellowship at MIT on energy and climate.