Editor’s note: Concerns about climate change causing or aggravating public-health problems are nothing new. Experts have discussed the potential prospects for manmade global warming to harm people’s health in various ways for years now.

One current example: The climate/health issue has been in the media spotlight again lately in connection with the massive wildfires in Canada’s Alberta province. One fire expert in drought-gripped California, echoing numerous earlier warnings, said “more frequent superfires” like the Canadian blazes are expected with droughts and heatwaves resulting from climate change. “This is an example of what we expect — and consistent with what we expect for climate change,” a wildfire researcher in Alberta said. And the connection to public health? Another scientist in Alberta said the impacts of the current wildfires there mean nearby residents have been breathing “lungfuls” of toxic substances in smoke. He predicted a huge “toxic surge” in the ash that will wash into waterways.

Last month, U.S. health officials issued a report, reviewed by the National Academy of Sciences, which declared that “climate change is a significant threat to public health” and summarized scientists’ thinking about potential impacts. They included heat-related death and illness from extreme heat; various illnesses from worsened air quality involving both manmade pollutants and increased allergens; drowning and injuries from flooding; water-related infections from microbes related to warmer water and precipitation changes; food-related infections from higher temperatures, and heightened risk of diseases contracted from insects with shifting populations and geographical range.

This article is the first in an occasional series in which Texas Climate News will examine climate-related health issues in Texas and what Texans are doing (or not doing) to address them. In this article, Greg Harman, a San Antonio journalist and TCN contributing editor, provides a thoughtful overview and analysis of the subject of mosquito-borne tropical illnesses.

+++++

By Greg Harman

Texas Climate News

West Nile. Dengue. Chikungunya. In recent years, this trio of potentially deadly mosquito-borne viruses carved out a definite niche in the growing catalogue of American anxieties.

It’s no wonder. The establishment of West Nile virus in the United States and growing number of dengue cases pose potentially serious threats to public health. Although there have been no dengue-related deaths in Texas since it resurfaced in the state in the 1980s, the World Health Organization estimates about 2.5 percent of those with severe dengue cases die. In the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 5 percent of those hospitalized nationally with West Nile Virus in 2012 died. Chikungunya rarely leads to death, but its symptoms can be “severe and disabling,” the CDC says.

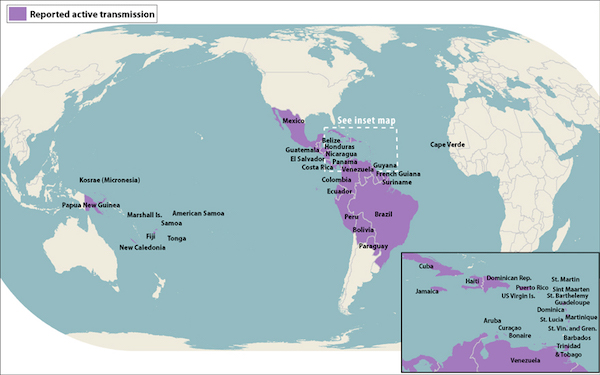

Moreover, since the turning of the new year, newcomer Zika has virtually eclipsed all three of those illnesses after it showed up in Brazil last year and then spread through other Latin American and Caribbean nations as far north as Mexico.

Special worry about Zika is, perhaps, not without reason. While not the most deadly of the expanding tropical diseases, Zika is best known for its recently confirmed link to microcephaly, or limited brain development, in unborn babies, the visual evidence of which is a frequent companion of international news reports

To date, there is no vaccine approved for use in the United States to prevent infection of any of these diseases. And there is no known cure.

Yet, as bad as the situation may appear, it can get worse. In fact, global warming and increased economic globalization – two major factors driving the rapid appearance of new tropical diseases in the U.S. – are only accelerating. (In the case of dengue, it’s a reappearance – “breakbone fever,” as it’s also known, has a long history in Texas.)

Some researchers have emphasized the expansion of trade, including, as just one example, the used tire trade between the U.S. and Southeast Asia, to explain how infected mosquito species are given free passage across oceans. Others consider how the expansion of the earth’s tropical zone provides fertile new habitat for bloodsuckers that thrive in warm, wet climates.

“Global warming definitely increases the chance of these diseases,” Dr. Manjunath Swamy, co-director of the Center of Emphasis in Infectious Diseases at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center in El Paso, told Texas Climate News. “Projections hold that as the temperatures rise from global warming and precipitation increases, the mosquito population will very likely increase.”

Virtually unknown in the United States until a 1999 appearance in New York City, West Nile virus has since become firmly established, with human infections being reported in every state but Alaska. Texas regularly ranks high among states for the number of annual cases. In 2012, the state was the epicenter of a major outbreak that resulted in 1,890 infections and 89 deaths, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services.

The 2012 West Nile explosion (100 to 200 annual Texas cases have been more typical) followed a perfect climatic setup involving a warm winter and tightly stacked drought and heavy rainfall events that forced the mosquitoes to “congregate,” University of Texas-Southwestern epidemiologist Robert Haley told the Washington Post late last year.

“Climate change is broadening the tropical latitudes, and Texas is going to be tropical eventually,” Haley said, adding that we can “roughly predict that tropical diseases will be part of our future.”

Texas’ dengue hot spot

Certainly, warmer and wetter weather conditions are understood to be critical drivers of mosquito activity, including mosquitoes of the Culex genus, principal transmitter of West Nile to humans, and Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, important transmitters of dengue, chikungunya and Zika. However, there has yet to be any definitive study demonstrating how such climate changes could increase the risk of mosquito-borne illness in Texas. That’s the gap that Texas Tech University graduate student Kelly Neely, who has been collecting and parsing data on mosquito habitat in the Rio Grande Valley city of Brownsville, hopes to fill.

“I knew I wanted to do something with weather, one of my passions, and with one of my other passions, which is infectious disease,” Neely said, adding that she sought a research topic “that can actually be used to help the public.”

Her decision to target Brownsville was anything but random. The fast-growing Cameron County city – situated at the southernmost tip of Texas, just across the international border from Matamoros, Mexico – has become the state’s hot spot for dengue since health officials said “sporadic cases” began to be reported in South Texas in 1980.

Unlike West Nile, dengue, which health experts call a “re-emerging” disease, has yet to establish itself in the United States, though it is endemic throughout tropical regions including northern Mexico. Only a relative handful of dengue infections are believed to have been acquired locally in the U.S. in recent decades. Most commonly, Americans who contract the dengue virus do so during travel outside the country and then bring it home in their blood. The potential for that to happen is illustrated, for instance, in the daily, to-and-from surge of thousands of commuters between Brownsville and Matamoros.

Since 1980, Cameron County has had Texas’ highest dengue tally. From 1980 through 2014, 594 dengue cases were recorded statewide, of which 394 were “imported,” 86 were believed to have been acquired locally, and the remaining 34 were contracted at locations unknown, according to the Department of State Health Services. Cameron had the biggest county total during that 35-year period – 115 cases, of which 52 were classed as “imported,” 47 were believed to result from local infections, and 16 were of unknown origin.

In 2013, a dengue outbreak that public health officials described as an epidemic spread across northern Mexico, including the state of Tamaulipas, where Matamoros is located. That city, just across the Rio Grande from Brownsville, had recorded more than 400 cases by Sept. 11, according to a Monterrey newspaper. Texas recorded 95 dengue cases that year. Cameron County was hardest hit with 37 cases, including 21 believed to have been locally acquired and five of uncertain origin. Adding another two locally acquired cases in nearby counties, it was the biggest number of locally acquired cases in South Texas since occasional outbreaks began in the region 34 years earlier, according to a 2014 report by local, state and federal epidemiology researchers.

Neely was inspired to undertake her research project in Brownsville, however, by information about a 2005 dengue outbreak in which 25 cases were reported in Cameron County, three of which health officials concluded were apparently locally acquired.

According to a 2007 report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), a joint investigation by Texas, Mexico and CDC officials concluded that the 2005 outbreak included an increased percentage, compared to earlier outbreaks, of dengue cases in both nations that qualified as the more severe and potentially life-threatening dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF).

Infection with one of four dengue virus types provides lifetime immunity against that type, but a later infection with another virus type puts a person at increased risk of developing DHF. More than 200 of more than 1,200 cases reported in Mexico met DHF criteria, according to the CDC report, and in Cameron County, 16 of 25 cases qualified as DHF.

In addition, a survey of Brownsville residents found that 38 percent had dengue antibodies, which suggested that “a substantial proportion of the city population has been infected by the dengue virus and might be more susceptible to DHF if they receive a second infection,” the CDC report said. (A survey in Matamoros found 76 percent had been infected.)

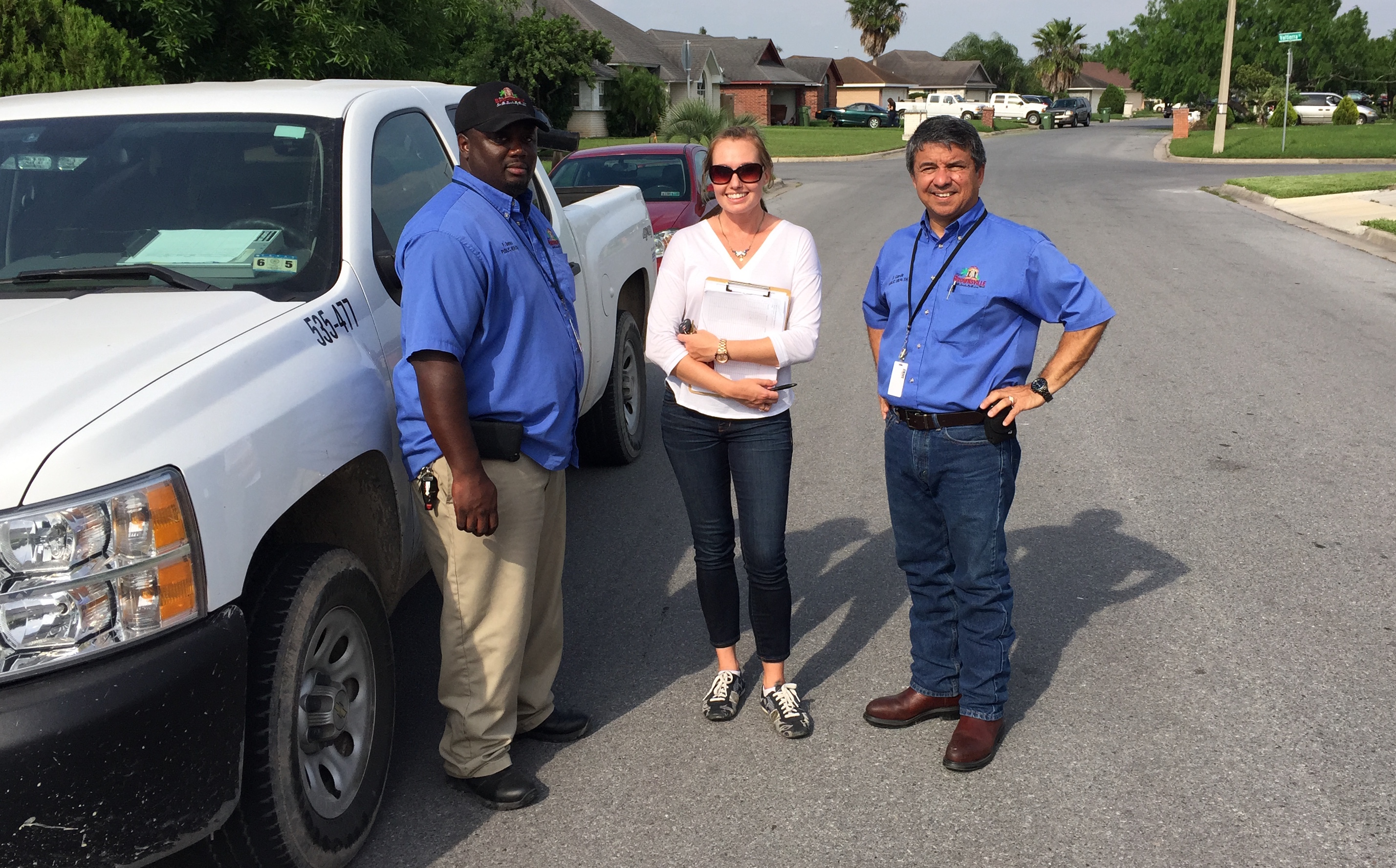

Kelly Neely worked with Fred Barnes and Eraquio Garcia of the Brownsville Public Health Department in conducting her survey of possible mosquito breeding sites.

Investigating the climate link

Assisted by officials of Brownsville’s Public Health Department, Neely spent several days collecting data related to potential mosquito breeding sites – things like tires, buckets and potted plants. The effort focused on two neighborhoods – one where dengue cases were reported in 2005 and one where none were reported.

To say it was an unpleasant experience is an understatement.

“I was hosing myself down with insect repellent,” Neely said. “We used copious amounts of bug spray with DEET, and it did absolutely nothing to stop the mosquitoes. I ended up with at least three dozen bites on my body after one day.”

Neely, guided in her research by scientists at the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Colorado, plugged her collection of habitat data along with daily weather data into a computer model known as Skeeter Buster, developed at North Carolina State University, to project how mosquito populations may shift in Brownsville over coming decades in a changing climate.

She ran the model for a variety of different future scenarios under two hypothetical emission scenarios – a “doomsday” scenario, in which humanity makes no net reductions in planet-warming carbon pollution and a scenario envisioning “fairly significant cuts in emission growth.”

This large open drum, holding water at a Brownsville residence, was noted during Kelly Neely’s survey of mosquito breeding sites. This container was one of several such drums in the same yard, located in the neighborhood where dengue cases were reported in 2005, Neely said.

For each emission scenario, Neely used Skeeter Buster to make projections for six different climate models’ scenarios in “near-century” (2025-32), “mid-century (2040-47) and “end-of-century” periods. The result, she said, “was an ensemble of potential realities in terms of mosquito populations.”

For the Brownsville neighborhood with reported dengue cases in 2005, Skeeter Buster showed an increase in average yearly “parous” female mosquitoes – those that have ingested blood and laid eggs – over the three time periods studied under both emission scenarios and all six climate models.

“For both neighborhoods, the model predicted an earlier start to, and expansion of, the mosquito season, with higher numbers of parous females as time progresses towards the end-of-century time frame (2090-2097),” Neely said. “A positive correlation was also observed between increasing temperatures and increasing numbers of parous females.”

She stressed to TCN recently that her study is still a work in progress, with a number of uncertainties, and that the tentative findings still must be validated with actual mosquito-population data collected by Brownsville officials in order to assess the accuracy of her application of the Skeeter Buster model.

With such confirmation, however, her findings could provide yet another wakeup call for the state’s surveillance programs, particularly in South Texas.

“What I would like to do is to give my results to the Public Health Department,” Neely said. “My thoughts are, if they know what could be coming in the future, they might be more inclined to develop new strategies or alter existing ones to combat the mosquitoes, since that is the source of these infections that are becoming increasingly more prevalent.”

Without mentioning climate change, the 2007 CDC report and the 2014 report by local, state and federal health experts already both recommended strengthened surveillance for dengue.

Challenges face monitoring efforts

But one of the major challenges fighting infectious disease along the U.S.-Mexico border is the low-to-no resources committed to monitoring mosquito populations, a task the state generally leaves up to local communities. The poverty of the Rio Grande Valley means attaining risk-appropriate funding is difficult, if not impossible.

“Because it’s such a financially poor region there’s not a lot of property tax money that can go toward mosquito prevention and control – certainly not like Dallas or Houston,” said Christopher Vitek, an assistant professor of entomology at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. (Harris County, where Houston is located, has one of the nation’s biggest mosquito-control operations and added Zika this year to other diseases for which it monitors.)

Since 2008 Vitek has researched mosquito ecology and disease transmission in the Valley. “The state does provide very good testing services, but they’re not continuously available. Or you may be able to access them only under certain circumstances,” he said.

A spokesperson for the Texas Department of State Health Services confirmed that state entomologists typically are only in the field working directly with local communities under special circumstances, such as the 2012 West Nile outbreak in Dallas, where roughly 400 of the state’s 1,890 infections occurred.

Zika’s appearance is another of those special circumstances. “It’s most likely we’ll see it down in the Valley, so that’s where we’re keeping an eye out for it right now,” said the spokesperson, Chris Van Deusen.

According to a March press release, Department of State Health Services employees began helping “monitor mosquito activity” with a team dispatched in February to collect samples around the Rio Grande Valley. That same release includes several recommendations for “local leaders,” including the expansion of monitoring and surveillance work.

Vitek said that even since Zika made its appearance there hasn’t been any significant increase in resources for monitoring or surveillance along the border. Mainly, he said, there has been a sudden emphasis on enhanced coordination among local agencies, the state, and academic researchers. “There’s certainly more awareness, but there’s always that distance between awareness and knowledge and funding,” he added.

And that is not, in itself, too troubling. In spite of the amount of media attention given to Zika due to the microcephaly link, he said that chikungunya and dengue still pose a greater public health risk. “With Zika, 80 percent of those infected are going to be totally asymptomatic. For the others, they may feel like they have a bad cold or something.”

Impact of increasing travel

Vitek emphasized that while global warming will likely extend the range of the mosquito species capable of carrying such viruses (and, hence, bring the potential for new infections), it is increasing international travel that all but ensures novel-sounding viruses will be making more regular appearances inside the U.S. That’s one reason why researchers are concerned about the lack of investment given to monitoring activities at the local, state, and federal levels.

“We really need to improve on that,” said Mary Hayden, research scientist with NCAR’s National Applications Laboratory, who has been helping Neely with her current research. “Especially in areas that are likely to be susceptible. I mean Brownsville, Texas, has had two outbreaks of dengue, in 2005 and 2013. We know the vector (mosquito species that can transmit illnesses) is there, we know the potential for transmission is there, and yet there’s no sustained surveillance along the U.S.-Mexico border in many regions.”

Along with dengue and West Nile, the chikungunya virus – which concerns Swamy more than those two diseases – has started showing up in Texas thanks to the expansion of global trade, shifting human behaviors and changing weather patterns. “It’s an exotic disease here and people do not have immunity,” he said. “ If it spreads, it’s really going to be a problem.”

Like dengue, chikungunya cases in the U.S. have centered around areas that receive large numbers of international travelers, including New York, New Jersey, Florida, California and Texas. The chikungunya virus, which first appeared in the Caribbean in 2013, made its first Texas appearance in the summer of 2014, with 116 cases logged by that Dec. 31 by the CDC. The first locally transmitted cases in the U.S. were reported in Florida that same year.

Public health agencies are bracing for the appearance of Zika in local mosquito populations, possibly as soon as this summer. Thirty-two of the 33 Zika cases confirmed in Texas by May 10 have been travelers infected outside the country, while the remaining case resulted when a Dallas County resident had sex with a person who had been infected abroad, according to state health officials.

Of course, even the expansion of mosquito-conducive climate conditions – say, a reduction in frosts and freezes that keep populations in check – does not automatically mean a corresponding increase of infections.

Public health programs are a big factor, as is personal avoidance of mosquito bites through the use of air conditioners and window screens. Greater use of air conditioners and screens among U.S. residents near the Rio Grande, compared to less affluent areas nearby in Mexico, is thought to be one of the major reasons for lower infection rates in the U.S. The way that people keep their yards, a key focus of Neely’s research, is another risk factor.

“There are areas [of Brownsville] that have containers lying out in backyards collecting water, they’re harboring these mosquitoes,” Neely said. “It will need to change. Because if we do see higher temperatures and more rainfall, it could definitely cause a very serious problem for the people who live there.”

However, the public health director in Brownsville “feels like his town is going to battle alone” in its mosquito-control efforts – with a yearly budget of just $225,000, USA Today reported last week, in an article headlined “Gulf Coast could be ground zero for Zika.”

Arturo Rodriguez, the city health director, told the newspaper he has had more communication with his public-health counterparts in Mexico about Zika than he has with U.S. officials: “We literally have to fight this issue on our own. We have to bootstrap ourselves. We have a very limited budget.”

Rodriguez said he believes Zika will show up in Brownsville eventually and all the city can do is to try to “minimize the risk” for citizens.

Countries where active transmission of the Zika virus had been reported by May 11, 2016, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Despite limited government resources at the local and state levels, entomologist Vitek’s ambitions are high for the Brownsville area. “Our hope is to have a relatively evolved surveillance program which will identify mosquito vectors so we can know where the populations are, to test those vectors to see if they’re infected with disease, to really get a much stronger handle as to what’s going on in the region,” he said.

“We could start to identify when risk factors are increased. If we started to see an increase in number of mosquitoes, we’d be able to alert control agencies to say, ‘Hey, you need to start spraying in that area,’” he said. “We’d also be testing for diseases so [we could] start controlling the mosquito population prior to an outbreak. To the best of my knowledge, there has never been any kind of long-term continuous surveillance effort.”

In spite of the severe challenges climate change represents for today’s industrial society (and, truly, the biosphere at large), perhaps there is a small upside to ongoing human-caused warming in the area of mosquito-borne diseases.

The average annual high temperature in Brownsville is now 83.7 degrees Fahrenheit. Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, which carry dengue, chikungunya and Zika, are believed to lose their ability to reproduce in places with an average annual high around 95 degrees – a threshold that could be reached in the Rio Grande Valley this century, according to Neely’s research.

“A couple of the models show that happening by 2100,” Neely said. “That would be one positive if temperatures do reach that. Possibly one of the only ones.”

+++++

Greg Harman is contributing editor of Texas Climate News. TCN editor Bill Dawson did additional reporting for this article.