By Bill Dawson

Texas Climate News

With 367 miles of Gulf coastline (and 3,359 miles of total coastline, including tidal inlets), Texas is unquestionably susceptible to sea-level rise and associated hazards that climate change is aggravating, especially storm-driven flooding.

That much has been accepted by scientists for some time. But science constantly moves on, refining, advancing and correcting earlier findings and conclusions.

In recent weeks, a number of studies have added to researchers’ understanding of, and underscored their warnings about, the impacts that human-caused global warming is projected to have on coastal regions in decades and centuries ahead.

Considered together, these studies show how research is continuing to magnify concerns about the recurring conditions that coastal areas, including the swath of Texas stretching from Beaumont-Port Arthur through Houston-Galveston and Corpus Christi to Brownsville, will increasingly have to deal with.

Here’s a summary and reading guide for some of the recently published research related to sea-level rise, starting with an analysis that calculated the human influence on flooding that has already occurred in two Texas locations and 25 others in states with shorelines facing the Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico and Pacific.

+++

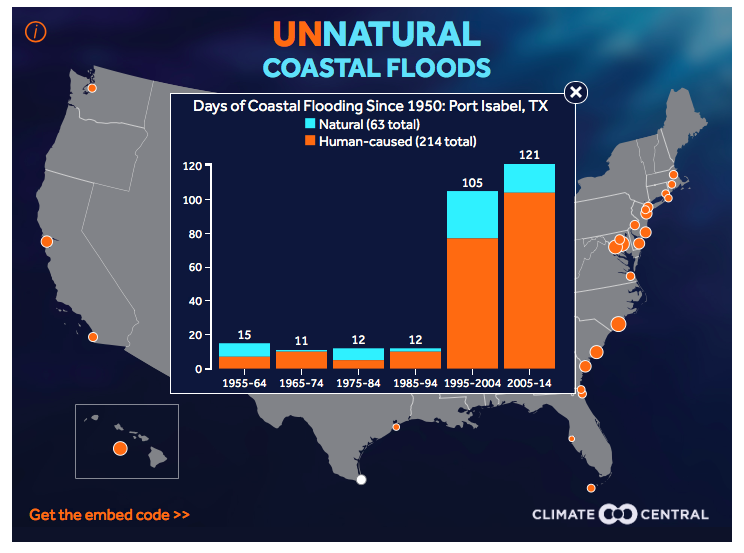

The analysis by Climate Central, a scientific research and news reporting nonprofit, concluded that 214 of 277 days when “nuisance flooding” occurred in the small South Texas town of Port Isabel since 1950 were caused by a rising sea level caused by global warming.

There were only15 days of nuisance flooding in Galveston in the same period, including three that were human-caused, the researchers calculated.

Their analysis found generally larger numbers of nuisance-flood days on the East and West Coasts, compared to the Gulf Coast. In Wilmington, N.C., for instance, 613 of 795 such days were attributed to human causation.

Benjamin Strauss, vice president for sea-level and climate impacts at Climate Central, explained:

Nuisance flooding is flooding that closes coastal area roads, overwhelms storm drains, and compromises infrastructure. It doesn’t wreck your home, but it could make it hard to get to work, or even to flush the toilet. The National Weather Service defines local nuisance flood thresholds based on decades of observing local impacts.

From 1950 through 2014, out of the 8,726 actual nuisance flood days that our analysis identified, 5,809 of them — two-thirds — would not have taken place if you remove [the] central estimate of human-caused global sea level rise [by researchers in a related study, issued simultaneously last week]. Even using a low estimate — one more than 95 percent likely to be too low — more than 3,500 of the flood days would not have taken place.

Climate Central’s analysis estimating the amount of “nuisance flooding” caused by human at selected coastal locations was based on research led by Robert Kopp of Rutgers University, which calculated global sea-level rise in the 20th century. Benjamin Strauss of Climate Central wrote: “In our report, we took a simple approach. We subtracted yearly estimates for human-caused global sea-level rise based on Kopp’s paper, from hourly water-level records at 27 tide gauges around the United States. Then we compared how many days the water level exceeded the local threshold for nuisance flooding — with or without our subtractions.”

+++

The other study in question, upon which Climate Central based its estimates for specific U.S. coastal sites, was authored by an international team of researchers led by Robert Kopp of New Jersey’s Rutgers University. It was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The New York Times reported:

In the second study, scientists reconstructed the level of the sea over time and confirmed that it is most likely rising faster than at any point in 28 centuries, with the rate of increase growing sharply over the past century — largely, they found, because of the warming that scientists have said is almost certainly caused by human emissions.

They also confirmed previous forecasts that if emissions were to continue at a high rate over the next few decades, the ocean could rise as much as three or four feet by 2100.

Experts say the situation would then grow far worse in the 22nd century and beyond, likely requiring the abandonment of many coastal cities.

+++

Reporting on the Kopp study, the Washington Post noted that another study, published on the same day last week in the same prestigious scientific journal, had yielded similar projections of sea-level rise during this century:

That paper, led by Matthias Mengel of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, also calculated that with unconstrained emissions, the Earth could see a maximum of some four feet of sea level rise by 2100. But it too acknowledged that the approach “cannot cover processes” like the possible collapse of the oceanfront glaciers of the West Antarctic ice sheet, which, it said, “is hypothesized to be already underway.”

The Post quoted Michael Oppenheimer, a climate scientist at Princeton University, saying the research in the two studies “begs the question of just how much disintegration of the polar ice sheets will contribute to sea level during the 21st century since neither type of model is adequate for capturing this growing and potentially disastrous contribution – and that is ultimately the most important unknown, both with regard to sea level and potentially with respect to the whole field of climate change.”

+++

Unsurprisingly then, several studies published recently focused on ice sheets (which cover land areas, such as most of Greenland) and ice shelves (floating coastline extensions of land ice, mainly found in Antarctica).

Two companion studies, published last month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggest that the Antarctic ice sheets are more suceptible than scientists had thought to increased levels of carbon dioxide, the principal human-produced pollutant warming Earth’s atmosphere, the University of Massachusetts reported.

One of the studies was a modeling effort, led by a researcher at the university, to simulate how the ice sheets responded the last time that atmospheric CO2 reached the level that is expected to be the case in about three decades, due to use of fossil fuels. In the second study, a New Zealand scientist and colleagues analyzed 3,735-feet deep sediments to reconstruct the history of Antarctica’s ice sheets.

Another study, published last month in Nature Climate Change and led by a German researcher, showed, according to a report by the Guardian, “that some large Antarctic ice sheets are dangerously close to losing the sea ice shelves that hold back their flow into the ocean.” The article continued:

Johannes Fürst, at the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg in Germany and colleagues, calculated that just 5 percent of the ice shelf in the Bellingshausen Sea and 7 percent in the Amundsen Sea can be lost before their buttressing effect [against ice-shelf loss] vanishes. “This is worrying because it is in these regions that we have observed the highest rates of ice-shelf thinning over the past two decades,” he said.

British researchers, meanwhile, published a study of mountain peaks and boulders above the ice sheet, showing levels it had previously reached in West Antarctica.

“The scientists report in Nature Communications that their results show how, during previous warm periods, a substantial amount of ice would have been lost from the West Antarctic ice sheet by ocean melting,” according to Climate News Network, which quoted John Woodward of Northumbria University, a study leader:

He says: “It is possible that the ice sheet has passed the point of no return. If so, the big question is how much will go and how much will sea levels rise.”

His fellow leader, Dr Andrew Hein, research fellow and manager of the University of Edinburgh’s Cosmogenic Nuclide Laboratory, says: “Our findings narrow the margin of uncertainty around the likely impact of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet on sea level rise. This remains a troubling forecast since all signs suggest the ice from West Antarctica could disappear relatively quickly.”

Another study about Antarctica, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in February was led by oceanographer John Anderson of Houston’s Rice University. It documented “how the ice shelf shrank during a period of climate warming following the [last] ice age,” about 10,000 years ago, the university reported.

“There are similarities to what we see the modern Ross Ice Shelf doing,” Anderson said. “The farthest boundary of the ice shelf extends nearly 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) from the grounding line, where the ice sheet is grounded in about 800 meters (2,625 feet) of water. That’s a condition that most glaciologists consider unstable, and it is not unlike the situation that existed prior to the big breakup that began 5,000 years ago.”

The present Ross Ice Shelf is about 500 miles wide and several hundred feet thick. Because the ice shelf is already floating, its breakup and melting would not, by itself, pose a risk of raising global sea level, Anderson said. However, he pointed out that the ice shelf acts as a brake to dozens of Antarctic ice streams and outlet glaciers, and ice flowing into the ocean from those would contribute to global sea level rise.

This 2014 image, taken from the International Space Station, shows shows Galveston Island’s vulnerability to rising seas.

+++

The same time span addressed in the Rice study – 10,000 years – figures prominently and ominously in yet another recent study, this one conducted by an international team of scientists led by Peter Clark of Oregon State University and published in Nature Climate Change. They calculated the period when people will have to deal with the impacts of long lasting CO2, previously and currently being emitted, on planetary systems.

Even meeting the tough challenge embodied in the international climate agreement reached in Paris in December – restraining manmade warming to 2 degrees Celsius (3.8 degrees Fahrenheit) – about a fifth of the human population will ultimately have to migrate from inundated coastal regions including New York, London, Rio de Janeiro, Cairo, Calcutta, Jakarta and Shanghai, the team concluded.

The Guardian reported:

The research shows that even with climate change limited to 2 C by tough emissions cuts, sea level would rise by 25 meters over the next 2,000 years or so and remain there for at least 10,000 years — twice as long as human history. If today’s burning of coal, oil and gas is not curbed, the sea would rise by 50 meters, completely changing the map of the world.

“We can’t keep building seawalls that are 25 meters high,” said Clark. “Entire populations of cities will eventually have to move.”

+++++

Bill Dawson is the founder and editor of Texas Climate News.