By Joseph A. Davis

and Bill Dawson

Texas Climate News

The world does not yet know what climate agreement might be reached by some 184 nations in Paris, but congressional Republicans already know they want to stop it.

As early as August, aides to Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky were contacting foreign embassies saying the United States wouldn’t keep any commitments that President Obama brought to Paris, because Republicans wouldn’t let him.

To be sure: Whatever accord is reached in Paris, no treaty will be submitted to the Republican-dominated Senate for approval. But both the House and Senate have voted in the past month to disapprove the president’s Clean Power Plan to reduce coal use in the production of electricity. The plan is both the administration’s principal executive regulatory tool to reduce greenhouse emissions and the foundation of its pledge to the Paris negotiations to reduce that pollution by 26-28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025.

The foreign minister of France, which is hosting the U.N.-sponsored climate talks, dismissed those congressional gestures with a Gallic shrug. They will have no effect, because President Obama can and will veto the Congressional resolutions and his opponents do not have the votes to override.

The House passed a pair of resolutions on Dec. 1, even as Obama was heading home from speaking to the climate conference in Paris, aimed at blocking his Clean Power Plan using a special procedure (called the Congressional Review Act) by which Congress can block regulations – but only if the president does not veto them.

The Senate had passed the same pair of resolutions Nov. 17. One addressed his limits on carbon emissions from new coal-burning electric power plants and a second addressed the Clean Power Plan’s restrictions on emissions from existing plants.

A Paris agreement, the administration asserts, will not be the kind of full-blown treaty that needs a two-thirds vote of approval by the Senate under the Constitution. Rather, they say, it will be the kind of international pact that can be inked by the chief executive alone.

Because of debate over this issue, whether the term “legally binding” can be applied to a Paris agreement has become a bone of contention – not only in Congress but in Paris. The issue gets complex and technical, and will be red meat for lawyers. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, a Republican strongly opposed to Obama’s climate initiatives, wrote Secretary of State John Kerry November 23 arguing that any agreement reached in the Paris talks would not be legally binding unless two-thirds of the U.S. Senate approved it.

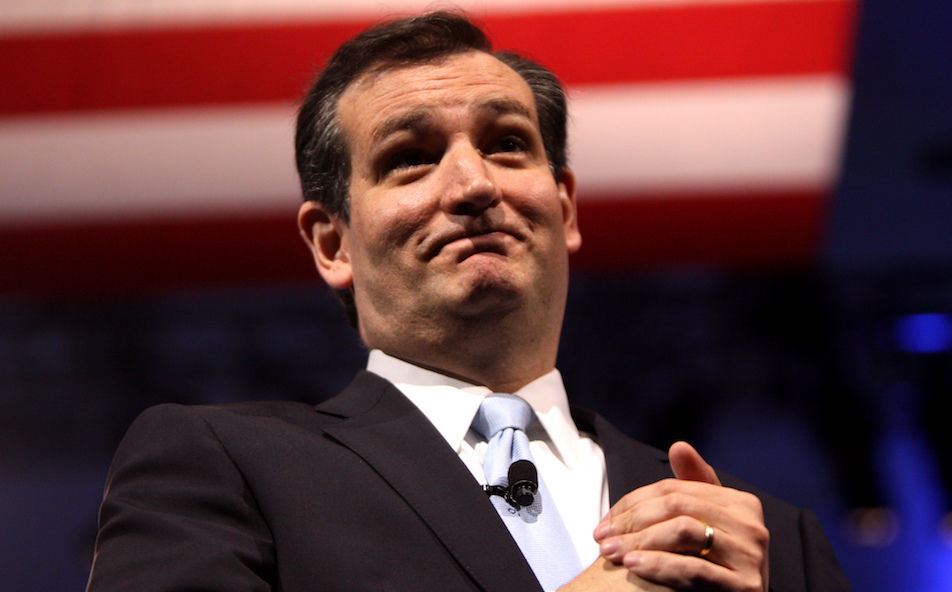

Then there is the court of public opinion. Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, a candidate for the GOP presidential nomination rising in recent polling, used that figurative venue yesterday to send a message to Republican primary voters and to climate negotiators in Paris about his disdain for the vast scientific consensus undergirding the conference and its sense of urgency.

Cruz did that by holding a hearing on whether the conviction that there is a major human impact on climate is based on “Data or Dogma.” The five-person witness list for the hearing included four invited by Cruz – a journalist and three scientists described by Science Insider, a publication of the American Academy for the Advancement of Science, as “known for their contrarian views on climate change.” [An earlier version of this article may have given the inaccurate impression that the three scientists do not think human activity is contributing to global warming. At least 97 percent of climate scientists agree the atmospheric warming trend of recent decades is very likely due to human influence.]

“Cruz hearing provides megaphone for climate doubts” was the headline on Washington-based Politico’s article previewing the event.

“The number of Republican lawmakers eager to denounce the scientific consensus around climate change has shrunk in recent years, although Cruz has never shrunk from such an opportunity,” Politico’s Eric Wolff noted. “Conservative voters are among the least likely to believe that human activity is to blame for climate change, making Cruz’s message a potent one in the Republican primary, where national frontrunner Donald Trump has also repeatedly dismissed climate science.”

The title of Cruz’s hearing, “Data or Dogma,” echoed one of his longstanding contentions – that the conclusion that the earth’s average temperature is warming with harmful consequences, and mainly because of man-made pollution, is more akin to religious faith than to evidence-based reasoning. “Climate change is not science,” he told right-wing radio host Glenn Beck in October. “It’s religion.”

Leading researchers have been equally harsh in their appraisal of Cruz. Last month, the Associated Press asked eight climate and biological scientists to grade a dozen top presidential candidates, Republicans and Democrats, on the scientific accuracy of their public pronouncements in debates, interviews and tweets.

The scientists, who were chosen by professional scientific societies and didn’t know the identities of the candidates whose statements they were grading, all gave Cruz the lowest grade of any candidate – an average mark of 6 on a scale of 0-100.

“This individual understands less about science (and climate change) than the average kindergartner,” one prominent climate scientist remarked about Cruz’s statements.

Cruz’s effort to discredit climate science (and Republican Texas Rep. Lamar Smith’s parallel effort in the House) will not directly undermine the Paris talks, where the negotiators represent governments that long ago moved beyond debate over the science to focus on how to respond to it. But before they conclude on December 11, the negotiations may yet stumble over the key issue of money: developing nations want more financial aid and developed nations have not yet come up with what they have pledged.

Congressional Republicans are exploiting this trouble spot. McConnell and other GOP leaders have vowed they will not appropriate any of the $3 billion Obama’s administration has pledged to the “Green Climate Fund.” They have also tried to insert a ban on those funds in the budget agreement still being negotiated.

In the end, Congress’ power to control purse strings is real, but U.S. withholding of money is not likely to stop a deal in Paris. What a President Cruz would do if he were to inherit a signed climate agreement from the Obama administration is another matter altogether.

+++++

Joseph A. Davis is Washington correspondent of Texas Climate News. Bill Dawson is TCN’s Houston-based founding editor.