With all the death and destruction that intense storms and massive flooding visited on Texas and Oklahoma this week, a new research report by the nonprofit Climate Central is especially sobering.

With all the death and destruction that intense storms and massive flooding visited on Texas and Oklahoma this week, a new research report by the nonprofit Climate Central is especially sobering.

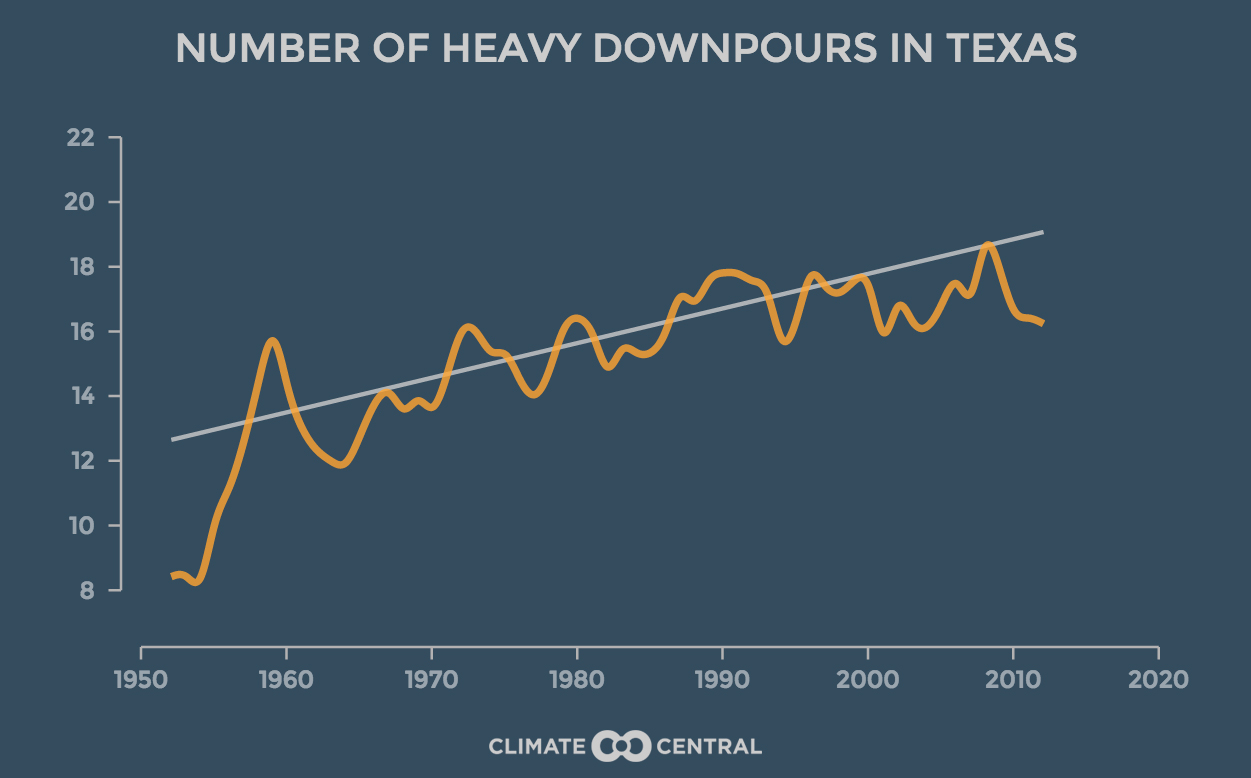

Consistent with climate scientists’ projections for a warming atmosphere due to heat-trapping pollution, the organization’s researchers found that the heaviest downpours have been occurring more often since 1950 in 40 of the 48 contiguous states, including Texas and Oklahoma.

From the Climate Central report, issued last Wednesday:

Record-breaking rain across Texas and Oklahoma this week caused widespread flooding, the likes of which the region has rarely, if ever, seen. For seven locations there [including Houston], May 2015 has seen the most rain of any month ever recorded, with five days to go and the rain still coming. While rainfall in the region is consistent with the emerging El Niño, the unprecedented amounts suggest a possible climate change signal, where a warming atmosphere becomes more saturated with water vapor and capable of previously unimagined downpours.

[…]

Across most of the country, the heaviest downpours are happening more frequently, delivering a deluge in place of what would have been routine heavy rain. Climate Central’s new analysis of 65 years of rainfall records at thousands of stations nationwide found that 40 of the lower 48 states have seen an overall increase in heavy downpours since 1950. The biggest increases are in the Northeast and Midwest, which in the past decade, have seen 31 and 16 percent more heavy downpours compared to the 1950s.

[…]

Extreme heavy downpours are consistent with what climate scientists expect in a warming world. With hotter temperatures, more water evaporates off the oceans, and the atmosphere can hold more moisture. Research shows that the amount of water vapor in the atmosphere has already increased.

Of the 50 cities with the biggest increases in heavy downpours from 1950-59 to 2005-14, four were in Texas, according to the Climate Central research. With their ranking on that list and percentage increase, they were McAllen (No. 1, 700 percent), Houston (No. 8, 167 percent), Austin (No. 31, 67 percent) and El Paso (No. 47, 40 percent).

He was not commenting directly on the Climate Central report, but John Nielsen-Gammon, the Texas state climatologist and an atmospheric sciences professor at Texas A&M University, noted after the recent Texas flooding that experts have observed a greater number of “heavy rain events, at least in the South-Central United States, including Texas. And it’s consistent with what we would expect from climate change.”

Climate Central’s findings were also in line with last year’s National Climate Assessment, a sweeping summary of the impacts of climate change across the U.S., assembled by a team of more than 300 experts from across the country and guided by a 60-member Federal Advisory Committee and reviewed by other experts including a panel of the National Academy of Sciences.

One of the National Climate Assessment’s “key messages” addressed heavy downpours:

Heavy downpours are increasing nationally, especially over the last three to five decades. Largest increases are in the Midwest and Northeast. Increases in the frequency and intensity of extreme precipitation events are projected for all U.S. regions.

For the Great Plains – the report’s eight-state region including Texas that stretches from the Mexican to the Canadian border – the National Climate Assessment had this to say:

Changing extremes in precipitation are projected across all seasons, including higher likelihoods of both increasing heavy rain and snow events and more intense droughts. Winter and spring precipitation and very heavy precipitation events are both projected to increase in the northern portions of the area, leading to increased runoff and flooding that will reduce water quality and erode soils. Increased snowfall, rapid spring warming, and intense rainfall can combine to produce devastating floods, as is already common along the Red River of the North. More intense rains will also contribute to urban flooding.

Katharine Hayhoe, director of Texas Tech University’s Climate Science Center and a lead author of last year’s National Climate Assessment, provided this comment about the Texas flooding to the New York Times:

One of the most important reasons we care about climate change is because it exacerbates the risks we already face today. Texas is home to many of the fastest growing metro areas in the U.S. This rapid urbanization and development changes the face of the land, increasing flood risk at a time when, at least for the eastern half of the state, the risk of heavy downpours is also on the rise.

Echoing Climate Central’s reference to scientists’ views on the connection of global warming, ocean evaporation and rainfall, Eric Berger, the Houston Chronicle’s science writer, wrote an explanatory article about the weather pattern that generated the recent Houston flooding, which stressed the Gulf of Mexico’s role in supercharging the thunderstorms that poured so much water on the metropolitan area:

On Monday night the heavens opened over Houston, dousing the city with some of its heaviest rains since the near biblical floods of Tropical Storm Allison.

While forecasters predicted a wet Memorial Day weekend, no one expected as much as one foot of rain to fall during a single night, nor the ensuing mayhem caused by widespread flooding.

So what caused these intense storms to regenerate, and dump 162 billion gallons of water on Harris County? There’s only one answer, the Gulf of Mexico. It provided the additional fuel for storms that, had water been collected across the county, could have filled the Astrodome more than 500 times.

– Bill Dawson

+++++

John Nielsen-Gammon and Katharine Hayhoe are members of the TCN Advisory Board.