By Joseph A. Davis

Texas Climate News

Outside the Senate Environment Committee room on Wednesday, Democratic senators were talking about science. Inside, Republican senators were scolding the Dems for boycotting the vote on confirmation of Scott Pruitt as administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Pruitt casts doubt on (some say “denies”) the vast scientific consensus on the manmade, hazardous nature of climate change.

The committee meeting was just an opening round. A day later, the Senate panel’s Republicans approved Pruitt’s nomination. And as Donald Trump settles into the White House and Republicans start cranking out his agenda and finalizing their approval of his nominees for key positions, it is clear that climate science and many other sciences will be taking a political drubbing.

Trump himself called manmade climate change a Chinese “hoax” before the campaign (and just an unattributed “hoax” during the campaign), though nominees Pruitt (EPA), former Texas Gov. Rick Perry (Energy Department), and Ryan Zinke (Interior Department) pulled up short of such language in confirmation hearings. (Perry, for instance, did not repeat his one-time – and evidence-free –accusation that climate scientists “manipulate” data for money.)

Scientists shuddered upon hearing that Trump had tapped Myron Ebell of the free-market-promoting Competitive Enterprise Institute to lead the transition team for EPA. Ebell had burnished a reputation as a climate-science denier during the George W. Bush administration – leading the charge to un-publish Clinton-era climate studies.

The early signs were alarming to scientific-integrity advocates, who want to protect government science from political pressures. The new administration’s EPA transition spokesman, Doug Ericksen, said January 25 that the work of EPA scientists, particularly on climate, would have to be reviewed by political appointees before it could be published. Whether this science ban will be temporary remains to be seen – but it set a tone.

It also recalled a key scandal of the George W. Bush presidency, when White House operative Phillip A. Cooney (fresh from lobbying for the American Petroleum Institute) was caught editing science reports in ways that downplayed scientists’ findings about the harmful consequences of climate change. Cooney, an attorney, quickly resigned from his federal job – and was then promptly hired by ExxonMobil.

Pruitt, as the GOP attorney general of Oklahoma, got major campaign funding from the oil and gas industry and led a multistate lawsuit against President Obama’s main climate initiative, the Clean Power Plan. An investigation by Eric Lipton of the New York Times showed Pruitt had taken language directly from Devon Energy, a major oil-and-gas company based in Oklahoma, put it on his state stationery with a handful of word changes, and sent it as a complaint to EPA.

Prospects for uncensored and unspun climate science may also be poor at other agencies that do such research. NASA, whose satellites do a big share of the federal government’s entire program of climate research, was threatened during the transition with having its whole earth-sciences program terminated.

Officials at another major climate-science agency, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), were very worried by the listing of a climate-science denier on its transition team. What will come of those worries remains to be seen. The picture is hazy: A NOAA spokesman said officials at the agency had “no contact” with the transition-team member. And Wilbur Ross, Trump’s nominee to head the Commerce Department (which includes NOAA), has pledged support for NOAA scientists’ freedom to conduct research and communicate their findings.

Another early sign of how politicized climate science may be in the Trump era will come Feb. 7, when the House Science Committee confronts EPA issues directly in a hearing. San Antonio Republican Lamar Smith, who chairs the committee, has hounded climate scientists at NOAA and may redouble his efforts in the next two years.

One of Smith’s methods has been to go after the emails of scientists using his committee’s extraordinary subpoena powers. Such tactics have been used by a wider array of groups – not merely against climate scientists, but against scientists studying the health effects of pesticides, for example. In fact, both sides in regulatory tussles – industry advocates and environmental advocates – are seeking scientists’ emails.

Scientists say this makes it hard to do science. In the last few years, legal groups like the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund have sprung up to support them.

Actually, this time around, scientists may have a set of other tools they can use to defend themselves, Washington Post reporter Chris Mooney points out. Those range from agency “scientific integrity policies” put into place during the Obama years to the Whistleblower Protection Enhancement Act of 2012.

Beyond such official avenues, officials have anonymously launched “rogue” versions of several federal science and environmental agencies’ Twitter feeds to counteract feared censorship or suppression of scientists’ findings by the Trump administration.

And in yet another sign that many are no longer content with decorous academic meetings, a large number of scientists and supporters are planning a “March for Science” on Washington April 22 (that’s Earth Day).

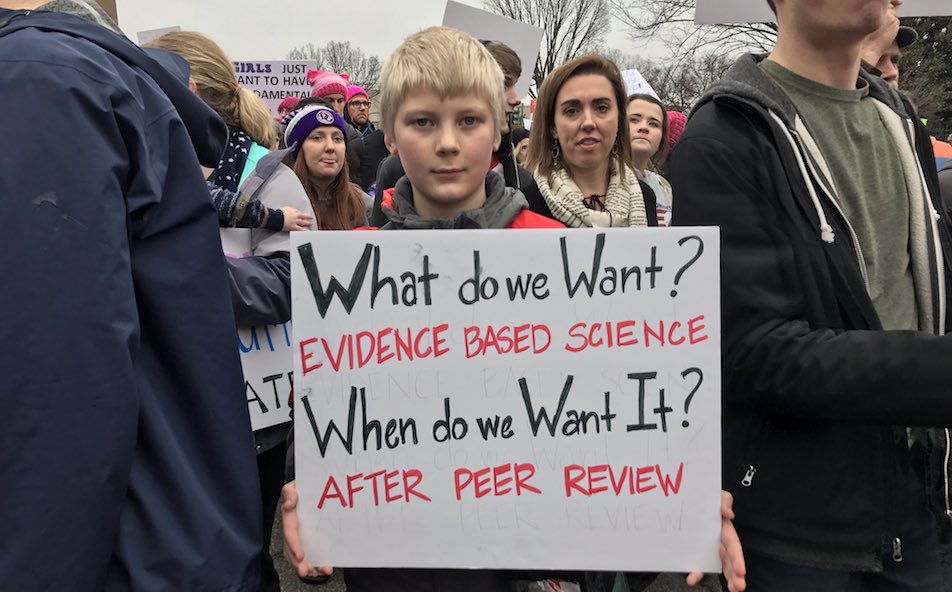

Perhaps that march will reprise the message on a sign seen at the Jan. 21 Women’s March. It read: “What do we want? Evidence based science. When do we want it? After peer review.”

+++++

Joseph A. Davis, a veteran independent journalist covering environmental and energy issues in the nation’s capital, is the Washington correspondent of Texas Climate News.